Pacifica Quartet set to launch exploration of Shostakovich

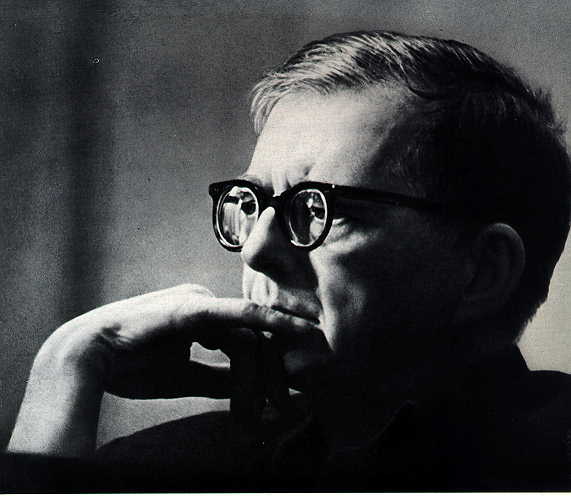

Beginning Sunday, Chicago audiences will have the rare opportunity to embark upon a musical journey that will take them into the most private thoughts of Dmitri Shostakovich, one of the 20th century’s greatest and most enigmatic composers.

The Pacifica Quartet is presenting Shostakovich’s complete string quartets this season, with all fifteen works performed in chronological order through February 27. The first of five programs will launch the cycle this Sunday, offering the String Quartets Nos. 1, 2 and 3 at 2 p.m at Roosevelt University’s Ganz Hall, with a second performance at 7 p.m. (The performances are part of the 16-month city-wide Soviet Arts Experience festival, which began earlier this month.)

The project came about over a conversation with Henry Fogel, dean of Roosevelt’s Chicago College of Performing Arts, as the Pacifica musicians were wrapping up their concerts of Beethoven’s complete quartets.

“We went out to dinner and thought, ‘What next?’” said Pacifica violist Masumi Per Rostad. “And Henry said, ‘What about Shostakovich?’”

“I said they really should think about doing the Shostakovich cycle,” said Fogel. “I think it’s the great quartet cycle of the 20th century, and it’s never been played in Chicago. And it’s absolutely the right music for them.”

Rostad says that it was daunting after doing all the Beethoven to think about leaping into Shostakovich and another fifteen quartets. “That’s a big project,” he said. “But all of us were so excited about it immediately. We just started immersing ourselves in it and that’s been our life now.”

Shostakovich’s large orchestral canvases seem to reflect in large part his response to the “Great Patriotic War” and the century’s roiling political upheavals—as well as his own shifting fortunes under the Soviet cultural commissars.

Yet the Russian composer reserved his innermost thoughts for chamber music. That seems particularly true in the quartets, where Shostakovich’s free approach to this most concentrated musical form could allow him to voice his deepest and most private hopes and fears.

Shostakovich came late to the string quartet, after he had already written his first five symphonies. The First Quartet dates from 1938, shortly after the triumphant premiere of his Symphony No. 5 restored him to the Soviets’ good graces, and something of that spirit—or relief—is felt in its relaxed lyricism.

“The great thing about Shostakovich,” said Pacifica cellist Brandon Vamos, “is that while he is working in established forms he’s very experimental within that, with a lot of variety. The First Quartet almost reminds us of Tchaikovsky. And the Second Quartet is anything but that.

“I think No. 2 is a fantastic quartet. It has a heavy Jewish inflection to it—the second movement is like recitative, very passionate. It’s very different from the First, and is a great, great piece.”

Shostakovich’s Eighth Quartet historically has been the most performed of the canon, in its original version as well as Rudolf Barshai’s effective arrangement for larger string ensemble, as the Chamber Symphony.

With its overt autobiographical allusions–the composer’s personal DSCH motif among them–and searching rumination amid desperate energy, the Eighth is, for many, reflective of the cycle as a whole.

Vamos doesn’t buy the notion that the Shostakovich quartets generally inhabit the same territory of gloomy introspection. “One of the reasons we do a complete cycle is that we learn these preconceived notions are not true,” he says. “We learned that with the Mendelssohn [set] for sure. Any great composer is constantly going to be looking for something new in their music, and that’s so true with Shostakovich.”

“There are some similarities within the quartets. I mean, it’s true that he uses a particular kind of waltz and that there are certain types of moods and characters that are recurring, and he uses motives that tie things together.”

“Certainly, the late quartets are very, very different and very unusual. After the Eighth and Ninth Quartet, it’s more sparse. Something happens.”

For about the past year while continuing to perform other music, the Pacifica members have been gradually expanding their Shostakovich canon beyond the three quartets (Nos. 3, 7 and 8) previously in their repertory. “We have about half of them under our fingers now and we’ve read through most of the rest,” says Vamos. “Each new one we tackle gets easier because we’re a littler more familiar with his language.”

Rostad believes there is a unique process in the discovery of these works, since once he and his colleagues start digging into the music “you start seeing Shostakovich a little bit differently.”

“When you first look at the scores, one of the things about Shostakovich is just how sparse it is,” said Rostad. “And when you actually play it what seems so simple is so emotionally ripe. And because of the simplicity, it gives you so much possibility for interpretation. No two performances of Shostakovich are ever similar.”

Likewise, the Pacifica’s cellist is struck by the wide divergence in the recorded performances of the complete sets, particularly between the Borodin, Fitzwilliam, and Emerson String Quartets. “There are such different approaches in articulation, mood and character,” said Vamos. “A particular passage can be almost completely opposite.”

Indeed, more than with most composers, Shostakovich’s music seems to morph radically in performance from what is sometimes baffling on the printed page.

“Your sense of the scope of the work and how things lie is so dramatically different,” said Rostad. “We can run through a piece in rehearsal and it just doesn’t quite hold together. And then we play it in a concert and suddenly ‘A-ha!’, so that’s what that meant.”

The Fifth Quartet is an example of the musicians’ perceptions of a work changing vastly with increased familiarity. “It took us a little while to get our hands on, and then we came to realize it’s a really unique quartet,” said Vamos.

“The solo writing for the cello is very dramatic and requires a lot of intensity and energy and tone production. Sometimes he puts me up in a high register and for a moment I feel like I’ve got a concerto.”

The complete cycle, which the Pacifica is also performing at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, will be recorded for the Chicago-based Cedille label. The group has already recorded four of the quartets (Nos. 3, 5, 7 and 8) and the first two double CDs will be released in the coming months. The set, due out in the fall of 2011, will include music of Shostakovich contemporaries like Prokofiev, Miaskovsky, and Weinberg. In the 2011-2012 season the Pacifica Quartet will take the complete cycle to London’s Wigmore Hall.

The shroud of mystery that surrounds so much of the private Shostakovich and what his music may or may not represent is a double-edged sword for interpreters. With an unceasing number of books, films and dissertations with “revelations” from supposed Shostakovich confidantes from Solomon Volkov on down, the debate continues to rage.

Rostad feels that even with all the accumulated political freight and acknowledging the constant threat Shostakovich lived under as an artist in the repressive Soviet regime, it can become too easy to impart a crypto-political subtext to every key change and dynamic shift.

“You want to know that [historical background] and you want to understand that,” said Rostad. “But at the same time you also want to just look at the score too.”

That said, Rostad said that, programmatic intent aside, there is an increasing depth and somber expression as the cycle unfolds, and, paradoxically, the textures become lighter and more spare.

“It’s the same kind of progression you see with a lot of composers in that the music becomes more cerebral as they get older,” he said.

“In a lot of ways there are aspects that are similar to Brahms. Obviously, the language and the feeling are different but there’s that same sense of strength and depth. There is this intense emotion that’s always under the surface.”

The Pacifica Quartet opens its Shostakovich cycle Sunday with String Quartets Nos. 1, 2 and 3. Performances are 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. at Ganz Hall at Roosevelt University. pacificaquartet.com; 847-242-0775

Posted in Articles