MCA has got the beat with premiere of work for 100 percussionists

Any concert that has 100 performing percussionists leading an audience of hundreds out of a theater and up two winding flights of stairs as part of the performance must not be ignored.

The world premiere of Marta Ptaszynska’s Voice of the Winds took place Sunday afternoon at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The event was the grand finale of a percussion program titled “Whisper(s)” by Matthew Duvall, and jointly presented by MCA with Contempo, the University of Chicago new music series, of which Ptaszynska is artistic director.

In the program note Ptaszynska says her “sonorous musical sculpture” takes its inspiration from John Cage, and “treat[s] ‘noise’ as an object of art.”

The dozens of percussionists–MCA did not provide an exact number–sat on stage until rising from their chairs and slowly proceeding up the two side aisles of the MCA Theater. In what the Polish composer called an “aleatoric processional,” the black t-shirt-clad percussion army played their small wooden and metal instruments along the way, almost like a ritual parade. Ushers directed the audience to follow the players out of the theater and up two flights of stairs to a third-floor hallway gallery.

This was the area for the second and main part of Voice of the Winds, which was (mostly) through composed. Duvall, Third Coast Percussion, and the beyond this point ensemble were the main driving protagonists spread out thought the cruciform space with scattered other percussionists also placed there. Ptaszynska herself performed on one of the drum sets.

As with most of the music on this program, much of Ptaszynska’s work was quiet, and performed on a vast array of instruments—high percussion, timpanis and drums of all sorts, wind machine, rubbed water goblets and bowls–you name it.

The music produced a bracing, often entrancing range of tangible colors and timbres, enhanced by the clarity of the acoustic. The music proceeds in atmospheric, slowly rising and falling waves. The score channels a kind of retro 60s-style “happening”—except with the modern phenomena of audience members taking selfies as they milled around and between the musicians. At one point a rolling sonorous climax is reached led by thundering timpani, which ebbs away to chimes and all the musicians playing shimmering triangles as they exit the gallery. Some thought that was the end of Ptaszynska’s piece, but it continued a few minutes more a floor below, which wasn’t made entirely clear.

Still, this was a singular musical event for sure. Members of Third Coast did a masterful job conducting and overseeing the huge and complex forces and ensuring that the sonic edifice stayed on track and never descended into mere chaos.

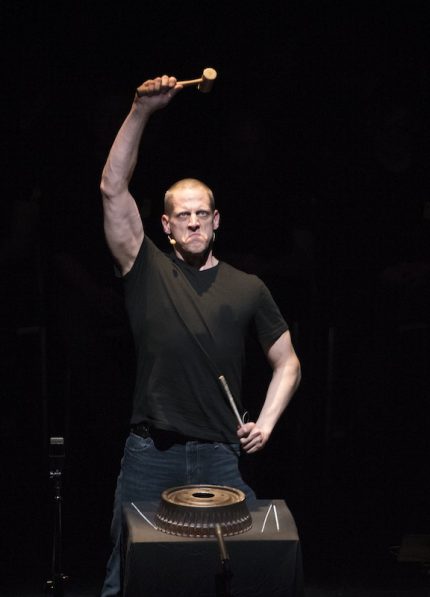

Much of the preceding program was primarily a one-man percussion show with Duvall, cofounder and percussionist of eighth blackbird, performing a variety of composers with some welcome items from the 20th century.

After accompanying the audience’s entrance with Erik Satie’s Vexations for piano, Duvall opened Part I of the afternoon with Matthew Burtner’s Broken Drum. Playing what appeared to be a drum brake of some sort, Duvall moved from rattling noises with a metal rod to faster and more contrapuntal textures in a kind of rhythmically sophisticated take on the quarter-caught-in-garbage-disposal school.

For Richard Reed Parry’s Heart and Breath Duvall was joined by his eighth blackbird colleague, pianist Lisa Kaplan. In this work Kaplan wears a stethoscope and the tempo of her piano phrases is determined by her heartbeat, as Duvall’s bowed percussion is by his breathing. As with many device-driven works, the setup is more interesting than the actual music, with the soothing piano chords and Duvall’s amplified respiration producing a kind of soporific, Lamaze Method meets New-Age minimalism.

The best item of the set was “Wail” an excerpt from John Luther Adams’ large-scale percussion work, The Mathematics of Resonant Bodies. Only JL Adams could make a siren an effective solo instrument. Cast against an ambient electronic cushioning, Duvall’s winding of the siren proceeded gradually from quiet to cochlea-piercing volume, the retro Atomic Age sonics somehow reflecting the current unsettled international situation.

Part II led off with David Lang’s Wed, a piano meditation inspired by a friend of the composer who married her partner shortly before dying from cancer. Duvall played this angular, touching work solidly, though one felt his somewhat impatient keyboard style didn’t give quite enough space for this intimate music to register.

Lang’s “Composition as Explanation 5” is part of a forthcoming larger work that he is writing for eighth blackbird. Here Duvall recites a lecture on art from Gertrude Stein, while simultaneously playing the cadences of the quasi-absurdist stanzas on a drum. Thin stuff as heard in its world premiere, but Duvall’s rhythmic acuity and coordination were undeniably impressive.

Morton Feldman’s The King of Denmark is characteristic with its shimmering range of jewel-like effects created on a variety of percussion instruments. Duvall produced a precise and nuanced array of arresting hues and timbres in music that rarely rises above a whisper.

Third Coast Percussion joined Duvall for John Cage’s Inlets. Each of the five percussionists sits in front of a bowl of water with pairs of conch shells on the side and microphones suspended above each bowl. Typically Cageian, Inlets managed to be theatrical, gimmicky and sonically intriguing all at the same time. The players alternated in producing delicate pointillist water sounds until one of them suddenly makes a loud primeval call on his shell and the house lights go out. The End.

Posted in Uncategorized