Moments of haunting beauty amid new-music cliches in “Savior” premiere

From Rossini, Verdi, and Tchaikovsky to Honegger, Norman Dello Joio and Richard Einhorn, the life of Joan of Arc has inspired composers for the past three centuries.

And now, Amy Beth Kirsten. Monday night’s MusicNOW program was devoted to a single work, Kirsten’s Savior. Commissioned for this 20th anniversary season of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s new-music series, Savior was presented in its world premiere at the Harris Theater.

Savior is not an opera but rather a musico-theatrical hybrid based on Saint Joan’s Passion. The hour-long work depicts, says the composer, “simultaneous temporalities.” There is “a flash of omniscience” reflected in “a barrage of time sound and memory” as Joan goes in and out of consciousness.

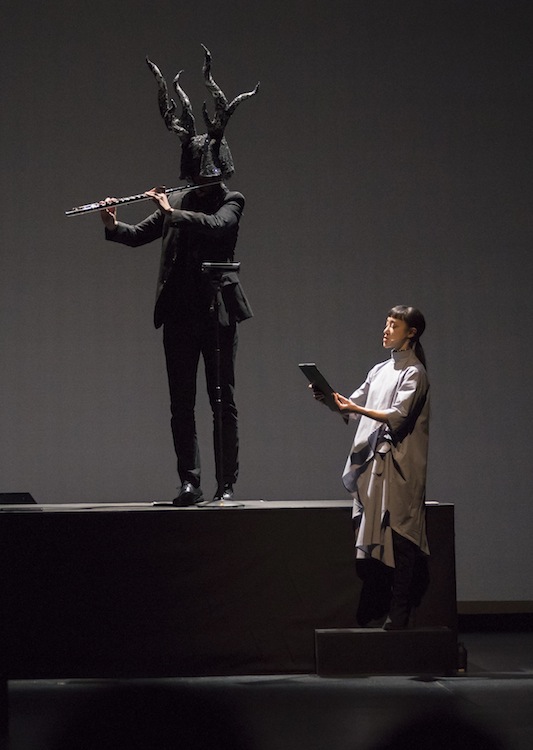

Joan is represented by a trio of amplified female vocalists who sing together and individually. A flutist wearing a stag’s mask represents a “divine messenger.” Musical backing is supplied by heavy electronics and two live players, a cellist and percussionist.

Rare is the multimedia hybrid that manages to make a unified convincing artistic whole out of such disparate resources. Unfortunately, Savior–despite arresting musical moments—doesn’t succeed in its ambitions any better than most.

The main problem is that the far-flung elements never cohere. A narrator (the excellent William Smillie) reads excerpts from the journals of the skeptical English general opposing Joan. The three women vocalists often walk together, holding hands, opening and closing their legs in unison in what seems to be a sort of feminist statement of solidarity. The stag-flutist walks on and off stage, standing high on a platform playing spare phrases and percussive blasts.

Yet the minimally staged presentation ultimately adds up to less than the sum of its parts. Most crucially lost here is any sense of Joan herself–her historic or religious significance, much less her courage or spiritual intensity.

Kirsten’s music is similarly uneven and too often derivative. The satiric, swooping vocal writing as the trio of women portray Joan’s questioners is right out of Cage, Berio and Ligeti. The instrumental writing is a kind of George Crumb Lite without that master’s uncanny ear for precise timbres and colors. And the breathy percussive blasts from the amplified alto flute—like the deafening electronic outbursts–never rise above current new-music cliches.

And yet despite its mixed inspiration and fitful pretentiousness, there are undeniable moments of haunting beauty in Kirsten’s score. The madrigal-like writing for all three women’s voices is lovely and reflects a 15th-century milieu, as does the spare luminous polyphony later on, suggestive of Perotin or Palestrina.

The female vocal trio (sopranos Molly Netter and Eliza Bagg and mezzo Hai-Ting Chinn) displayed staggering virtuosity and versatility– athletic and exacting in the leaping music and pure-toned and blended in their unison passages.

The playing of the three instrumentalists, also amplified, was on the same level.

Kirsten’s music for flute is the least interesting in the work, but Tim Munro performed the spare and percussive lines with typical polish and facility, as well as gamely entering the theatrical aspect, with his stag mask getup.

The climax of Savior is a spacious cello solo, played with rich tone and striking depth of feeling by the CSO’s Katinka Kleijn. Her colleague, principal percussionist Cynthia Yeh, delivered intense drumming and pointillist washes of color as needed.

Posted in Performances