Brahms’ Classical roots manifest in his most epic chamber works

In an era when we routinely hear and enjoy music of immense diversity from the 19th century, it may be difficult to imagine how polarized schools of Romanticism actually were in their day. In the era of Wagner and Brahms, few had the foresight to see value in the approaches of both, and for most, love of one meant having to detest and attack the other.

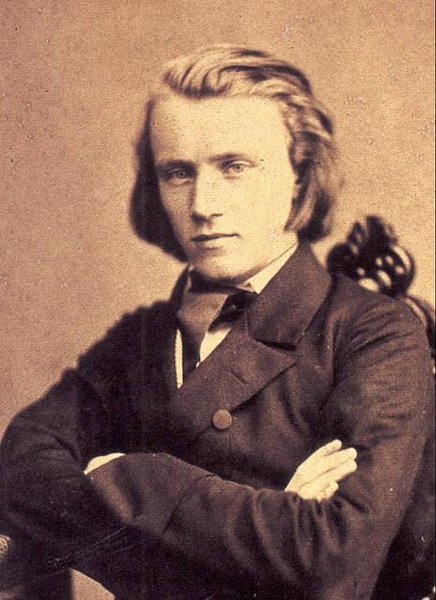

The Vienna critic Eduard Hanslick most symbolized this polarization, as a leading voice for anti-Wagnerian forces, and an advocate for his friend Johannes Brahms. In his early years, Brahms himself took an active role in such disputes, down to co-writing and signing an infamous incendiary manifesto against what he considered excesses in German music.

The year was 1860, the same year that Brahms wrote his String Sextet No. 1 in B-flat Major, Op. 18. With its innovative and Romantic transformation of standard Classical form, that piece ended up being a far more eloquent case for the 27-year old Brahms than any written manifesto.

As its performance on Sunday night’s all-Brahms program in Northwestern University’s Winter Chamber Music Festival reminded us, the Sextet No. 1i remains no less a tour de force even a century and a half later and remained a personal favorite of Brahms throughout his life.

Leaving aside the fact that the sextet genre offered Brahms the opportunity for more expansive harmony that the string quartet, this listener has always heard this piece principally as a trio in harmony: its most expressive moments consist of pairs of violins, violas and cellos playfully tossing about Brahms’ folk-like melodies and their transformations back and forth.

To make that work, of course, the ensemble has to elastically be of one mind both when they are split up in pairs and when they come back together as a full sextet, which was admirably the case at Sunday’s performance.

The cello section is the foundation, and holding down that fort was cellist extraordinarie Lynn Harrell — around whom this program was conceived — along with his one-time student and former Chicago Symphony cellist, Stephen Balderston, now string performance chair at DePaul University.

Harrell played the first cello part but the pair performed as a single unit and looked to their CSO colleagues — concertmaster Robert Chen, violinist Blair Milton and violist Yukiko Ogura, plus violist Roger Chase— for full support, which was provided with aplomb. Harrell subtly led the work’s tricky tempo fluctuations, assisted at times with a nod or two from Chen, particularly in the accelerando near the coda.

Thirty years later Brahms wrote his String Quintet No. 2 in G Major, Op. 111, a piece scored for nearly the same forces, minus one, but in this case, less is more. Here, the single cello part — played by Harrell — dominated the work often as a melodic bass line but taking the spotlight in its middle range as well. Chase played first viola, but otherwise the personnel was the same for the quintet as for the sextet.

Juxtaposing these two cello-centered works of Brahms from the beginning and end of his full development as a composer was a fascinating display of how the approach first displayed in Op. 18 came to freer fruition by Op. 111.

Posted in Performances