Gutiérrez, Kalmar strike sparks in Brahms concerto

Wednesday’s Grant Park Music Festival concert presented a nice balance of music that featured some breezy tidbits by Saint-Saëns and Bizet, coupled with a sterling performance of the Brahms First Piano Concerto by Horacio Gutiérrez.

The first half of the program was a perfect concoction for a late summer evening. As an opener, Saint-Saëns’ Marche militaire française was showy and brief. Conductor Carlos Kalmar brought a light touch to this forgettable piece, strings and brass nicely balanced and an impulsiveness that was quite enjoyable. With the brass singing out and the strings smooth and ingratiating, it was a French version of Rossini done with finesse and a bit of flash.

This auspicious beginning led into another rather short piece of French music, Bizet’s Symphony No. 1 in C. Written when he was just 17, it is the work of a very young man with its homages and ebulliences. Yet the work is actually quite sophisticated for all the borrowings from Rossini and the two symphonies of Bizet’s teacher, Gounod. It is a piece that exists as if caught in amber, since it lay undiscovered until the 1930s and represents an early phase in Bizet’s musical development.

The slow second movement contains a beautiful oriental-flavored oboe solo that contrasts with a slow fugal section in the low strings. Each of the four short movements has its own charm, from the bagpipe rusticity of the Scherzo to the scampering strings and cheerful march of the finale, and Bizet’s symphony was played with style and good humor by the Grant Park Orchestra.

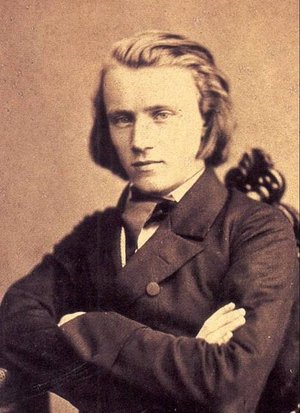

A quick changeover brought the piano on stage and the appearance of pianist Horacio Gutiérrez signaled the beginning of something much more substantial: an early masterpiece by the 27-year-old Brahms, which contains some of his most deeply felt and original music.

The Piano Concerto No. 1 was first performed in 1859 after a long and painful struggle with the material, during which time his mentor and friend Robert Schumann slipped into madness and, eventually, death. It seems to reflect Brahms’ deepest emotions, involving himself, Schumann, and Clara Schumann – his only muse in life.

But it isn’t necessary to know the biographical details to be affected by this bold and somber collaboration. In the capable hands of Gutiérrez and Kalmar, the music spoke quite eloquently for itself. After the extensive instrumental introduction, the pianist gently entered in a perfect balance with the orchestra, demonstrating here, as throughout the performance, a marvelous rapport between soloist and orchestra.

The long first movement, marked Maestoso, (majestic, or dignified) is an epic journey through a craggy emotional landscape. One can only wonder how the audience of the day reacted to such an outburst. (It’s interesting that the Bizet Symphony was written only four years previously.)

What stands out is how all the arpeggios, octaves, and trills seem to have a purpose. Unlike Liszt in his concertos, the technical elaborations lead to a musical and emotional goal that is ultimately resolved into a satisfying whole.

The middle Adagio movement is ideally as intense in its way as the more overt first movement. Here the noisy Grant Park environment milked the music of some of its rapt intensity. Still, it was never less than satisfactory and came to a perfectly judged close.

The artists moved right into the brusque and almost rollicking rondo Finale where again the equal partnership stood out. The bravura was varied by subtle changes and technical felicities, and the music-making was at a very high level.

Posted in Uncategorized