Tilson Thomas, CSO deliver a vital and eloquent Mahler 9

The greater the music, the more readily it responds to different interpretations. Gustav Mahler’s epic Symphony No. 9 may well be the most profound work ever written in the genre, yet even with the composer’s obsessive markings and instructions, this deep, searching music remains highly malleable and can bloom in the hands of podium guests with widely divergent approaches.

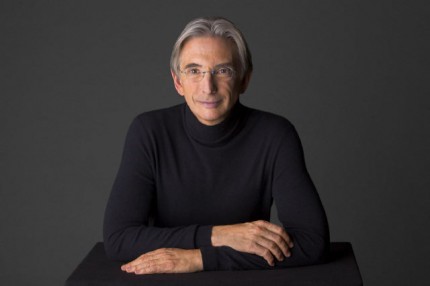

Thursday night it was the turn of Michael Tilson Thomas with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The American conductor is one of our finest exponents of Mahler’s music, as his performances and superb recorded cycle with his San Francisco Symphony have shown. Yet while he has been a semi-regular guest conductor with the CSO, his Mahler assignments in Chicago have been few, bafflingly so.

Thursday night’s vital and richly eloquent performance of Mahler’s epic Ninth showed what Chicago audiences have been missing and more than made up for the balance.

There are several superb Mahler conductors extant today: Riccardo Chailly, Christoph Eschenbach, Simon Rattle, and the CSO’s own former principal conductor, Bernard Haitink, who led the most recent CSO concerts of this work two years ago.

Yet I’m not sure Tilson Thomas has a current peer in this repertory. To be sure, Haitink’s 2011 performances were characteristically inspired: highly polished, scrupulously balanced and firmly objectivist in style.

Yet there is a raucous, subversive element in this music that gets somewhat subsumed with Haitink for all his textual probity. Tilson Thomas seems to get the best of both worlds, with attentive focus on details of dynamics, expression, and tempos shifts while also being free enough to invest the music with a raw vitality that is part of Mahler’s world as well, without crossing the line from sentiment to schmaltz. The performance also benefited from a different orchestral layout, with violins split, basses left and cellos left center.

Written at the end of Mahler’s life, the Ninth is imbued with a sense of departure and farewell—from his wife Alma, from the symphonic form as his last completed work in the genre, and from life itself. The opening two-note motif is like a sigh, the simplest of themes that grows from its warm first appearance in strings into ever more wide-ranging, harmonically complex regions, morphing into acidulous muted brass among other guises and timbres.

Thursday’s performance began in simple and straightforward manner, the opening theme almost briskly casual. Yet as the music develops, the performance seemed to organically gather power, force and ballast. Climaxes were imposing and full-blooded with brass having an apt raspy edge (and fine solos by Daniel Gingrich). The closing pages, coming full circle to the opening, were beautifully done with Mathieu Dufour contributing stellar flute playing.

The second movement went with a fast, aggressive quality, the Landler accents emphatically punched out by the cellos, with sardonic wind writing underlined. So too the ensuing Rondo-Burleske was wild and vehment, the winds—especially John Bruce Yeh’s uninhibited clarinet solos—thrown off with an antic, unhinged quality that almost seemed to have populist klezmer echoes. (The conductor’s grandparents were the Thomashefskys of Yiddish theater fame.)

Thursday’s performance was at its peak in the final movement, the long-breathed ebb and flow charted patiently yet with a firm sense of flowing momentum. The quiet sustained concentrated of the string playing was remarkable with the violins in particular rendering their music with an unearthly beauty in the final bars as the music slowly fades to silence. The valedictory feeling and sense of a hard-won elevated solace that seems to transcend the pain and suffering of earthly life, was most affectingly conveyed. Too bad about the isolated but loud coughs that diluted the spell in the final minutes of this memorable performance.

While there a few fleeting ensemble lapses Thursday night, the CSO members otherwise covered themselves in glory with outstanding corporate playing and individual contributions from Gingrich, Dufour, bassonist David McGill, trumpet Chris Martin, oboist Eugene Izotov and concertmaster Robert Chen. Let’s have Tilson Thomas back for more Mahler, please.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is invariably performed alone due to its length, weight and complexity. But leave it to Tilson Thomas, a master of quirky and distinctive programming, to serve a historically apt micro-prelude of sorts with Stravinsky’s Elegy for J.F.K.

This two-minute work for mezzo-soprano and three clarinets on a text by Auden is typical late Stravinsky in its taut concision. Yet the Elegy is clearly deeply felt by Stravinsky who met and greatly admired the young president. Kelley O’Connor sang the homage with dignified feeling, sensitively supported by clarinetists John Bruce Yeh, Gregory Smith and J. Lawrie Bloom, in a timely tribute on this 50th anniversary weekend of President Kennedy’s assassination.

The program will be repeated 1:30 p.m. Friday, 8 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. cso.org; 312-294-3000.

Posted in Performances

Posted Nov 22, 2013 at 1:37 pm by Alan D. Strange

I agree, Larry. MTT showed utter mastery of this piece last night and brought the orchestra to the height of its expressive powers. He is a true Mahlerian and inspired the CSO to play at the level at which it should perform this repertoire but has not always done so in recent times.

Posted Nov 25, 2013 at 2:37 pm by John Bostjancich

I attended the concert on Thursday evening and found it so moving that I returned on Saturday night. It was noteworthy how Maestro Thomas handled the coughing problem noted in the review on Saturday night.

After a first movement marred by the problem, Thomas left the stage and returned with two full handfuls of cough lozenges. He proceeded to toss them (underhanded lob) into the audience with the explanation that perhaps they would help those having a problem. He urged people to pass them on to those who could use them.

This could be viewed as a controversial approach. But Thomas’ words and, perhaps, his delivery worked! There was much less coughing heard in the next three movements. (Two or three muted coughs, however, during the quiet finale.)

I fully understand Maestro Thomas’ frustration. Here you have one hundred or so superb musicians who have each devoted hours to preparing this concert of one of the most moving pieces of music ever written. While coughing is not always avoidable, many times it can be stifled without undue discomfort. Saturday night’s performance after the first movement confirmed that. Hopefully we can all keep that in mind in future concerts. And, when we’ve got a touch of flu, the CSO makes it easy to exchange tickets for another performance. Finally, let’s unwrap our candies before the music starts.

We’re lucky to attend concerts by one of the finest orchestras in the world. Let’s do our part.