Tales of romantic obsession conclude Collaborative Works Festival

After basking in Brahms on Thursday, the Collaborative Arts Institute of Chicago (CAIC) closed its seventh Collaborative Works Festival with romantic song cycles—this time, of the small-R variety.

“Love’s Paradise,” Saturday’s program at the Ruth Page Theater, cleverly paired Arnold Schoenberg’s epoch-making Das Buch der hängenden Gärten (The Book of Hanging Gardens) and Leoš Janáček’s ambitious Zápisník zmizelého (The Diary of One Who Disappeared). Both are evocative tales of consuming lust, set in scenic locales and emotionally informed by events in each composer’s life.

Besides arranging a clever diptych, CAIC brought in dancers and video effects to accompany the Schoenberg and Janáček cycles, which mostly enhanced the experience.

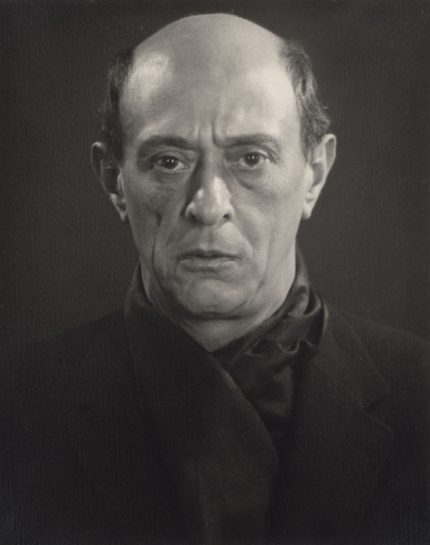

The Book of Hanging Gardens, which premiered in 1910, was Schoenberg’s first decisive foray into atonality (not serialism, as the program notes erroneously claim). Just two years earlier, Schoenberg discovered his wife Gertrude’s affair with Richard Gerstl, an eminent painter and family friend. The Schoenbergs eventually reconciled; devastated, Gerstl committed suicide in 1908. Schoenberg’s trauma from the experience seems to have informed his decision to set these 15 enigmatic poems by Stefan George: The narrator falls in love with a woman who eventually “leave[s] forever,” the garden left to rot in her wake.

Mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano assumed the role of lovelorn narrator, her gorgeously tempered voice—brilliant but never cutting, with a well-controlled vibrato—making her the evening’s clear standout. Though each song is blink-and-you-miss-it short, Cano and pianist Shannon McGinnis molded each into a densely emotive episode. The seventh song (“Fear and hope oppress me by turns…”) was a jagged expression of pain cast in a tug-of-war tempo; when singing of the narrator’s anxious rapture in the eleventh song (“I remember that like fragile reeds / We both mutely began to tremble…”), Cano’s voice became reticent and gauze-like.

Talented dancers Andrew Erickson and Kristen Hammer kinetically represented the star-crossed lovers, tenderly recreating the lovers’ first embrace. Erickson, who also choreographed the show, mostly kept the dancers’ movements as sparse and loosely programmatic as its source material, leaving some songs unchoreographed.

Janáček’s The Diary of One Who Disappeared is not quite a song cycle and not quite chamber opera, calling for tenor, alto, and an offstage vocal trio, plus piano. Written in 1920, the piece is part of the swath of late works dedicated to Kamila Stösslová, the much-younger, married woman with whom Janáček became obsessed. His incessant letters to Stösslová dwarf the amount he received in return, leading scholars to doubt she reciprocated the composer’s affections.

Unsurprisingly, The Diary of One Who Disappeared reads like Janácek’s fantasy of a love that never was: Jan, a farm boy, becomes infatuated with Zefka, who watches him from the woods while he works. According to Jan, because she is a “gypsy,” his family would never approve of her, so he keeps his distance—at least, at first. The two consummate their love, and Jan eventually leaves his family to be with his beloved and their newborn son, reputation be damned. Though Zefka is a singing role, she only appears for three of the 21 songs; true to life—or Janácek’s, at least—the majority of their courtship is relayed by Jan.

Though the cycle itself is a genre-bending delight, its execution was less polished than the preceding Schoenberg. Nicholas Phan interpreted Jan’s role with special sensitivity, portraying him as both swaggering cowherd and blushing virgin. Less consistent was the tenor’s vocal production; his singing often sounded strained in the high tessitura, jarringly so in the forte top Cs that conclude the cycle. As Zefka, Cano was vocally secure as ever but leaned less on physical stage presence, sometimes making for a stylistic disconnect between the two protagonists.

Both found a steadfast partner in pianist Craig Terry, who captivated with his powerful interpretation of the orgasmic piano interlude at the cycle’s heart. The “offstage” trio (sopranos Leigh Folta and Natalie Sherer and mezzo-soprano Micah Gleason), which narrates parts of the ninth and tenth songs, contributed ethereal, bell-like interpolations.

Hana S. Kim’s video projections, which included supertitles, were helpful as a narrative guide to this quasi-operatic work. However, they weren’t much more than that, with the blandness and occasional repetitiveness of an animated screensaver—certainly not obtrusive, but not particularly enriching, either.

Posted in Performances

Posted Sep 10, 2018 at 7:02 am by Jizungu

I felt robbed of the Schoenberg, owing to the management’s foolish decision to keep the house lights off, which made it impossible to follow the texts. (They did the same during Cano’s performance of Mahler on Wednesday.) This seemed doubly idiotic, given that few in the audience were likely to be familiar with the work. What were they thinking?