Sinfonietta closes season with aquatic theme, looks to the future

The outward theme for the Chicago Sinfonietta’s season-closing concert was music inspired by water or the sea. But it was hard not to be diverted by the imminent passing of the baton, as reflected in the divided podium duties Monday night at Orchestra Hall.

In March, the Sinfonietta’s founder and longtime music director Paul Freeman announced that he would be stepping down after more than two decades as conductor and guiding light of the orchestra, which is committed to diversity in its membership and repertoire. Next season amounts to an extended audition process of sorts with a variety of potential successors guest conducting the Sinfonietta.

That search effectively began Monday with William Eddins leading the second half of the evening’s program. Currently music director of the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra and former resident conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Eddins is a dynamic presence, bringing a coiled physical intensity to his conducting, at one point almost slipping off the podium in his excitement.

More crucially, he drew polished and responsive playing from the orchestra in two challenging works. Eddins’ direction of the Dialogue Between the Wind and the Sea—the third section of La Mer—-wasn’t the most subtle Debussy ever heard, but was strong on atmosphere and volatility, Eddins whipping up a cataclysmic tempest in the closing section.

The main event was the premiere of Aquadia by Michael Abels. A co-commission between the Sinfonietta and the Shedd Aquarium, Abels’ music will run on a perpetual loop at the Shedd as musical backing for the soon-to-reopen Oceanarium. (Eddins and the orchestra are recording the work today.)

Aquadia was performed Monday with projected digital images of waves, whales, and various Piscean creatures. The pictures were often captivating—-who can resist a baby whale cavorting with its mother?—–but the video and live performance weren’t always in synch, the screen sometimes going black while the music continued. Also a boisterous Latin-flavored musical section was twined with an unchanging monotonous shot of light streaming through the water, making one wonder if this was a technical glitch or just maladroit coordination between music and video.

The rule of thumb with this kind of video-accompanied live performance is that the greater the music, the more distracting the video. That was not the case, which is not to say that Abels’ colorful score doesn’t fulfill its utility. While rather slender and cinematic with a cheerful uptempo energy, Aquadia is attractive music, smartly scored. The new work received vital and brilliant advocacy from the Sinfonietta under Eddins’ direction, though the experience made me more eager to revisit the Shedd Aquarium than to hear Abels’ score a second time.

Music director Freeman was on the podium for the first half, which led off with the opening Overture from the Suite in F major from Handel’s Water Music. Freeman elected to use the Hamilton Hardy arrangement, which was a nice retro touch, even if the rendering was light on charm and rather rough-hewn in performance.

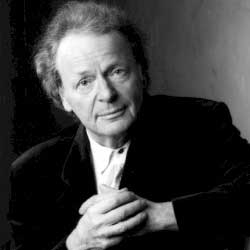

The sole non-aquatic work was Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1, performed by soloist Anton Kuerti. The Canadian pianist performed in the Sinfonietta’s very first season and it’s clear the Kuerti and Freeman continue to enjoy a simpatico musical relationship. The men showed close give and take in this performance, with Freeman eliciting alert and vigorous accompaniment from the musicians.

At 70, Kuerti maintains an estimable technique, and his passagework and diamond-bright articulation were faultless Monday. Kuerti clearly sees this early Beethoven work as more of the Classical era, playing with a quicksilver Mozartean approach that worked well in the opening movement.

Yet, considering Kuerti’s credentials—he has recorded all of Beethoven’s piano concertos and sonatas—this performance lacked the kind of individual profile and expressive detailing to make the concerto come alive. The slow movement was unsentimental to the point of coolness, rendered with a literal unyielding touch, dynamics hovering at an unvaried mezzoforte.

The final Rondo is one of Beethoven’s wittiest and most delightful inspirations, yet while played at a fast tempo with emphatic accents, the music rarely smiled. The performance would have benefited from Kuerti bringing some of the sparkle and playful nuance he displayed in the coda to the rest of the work.

Posted in Performances