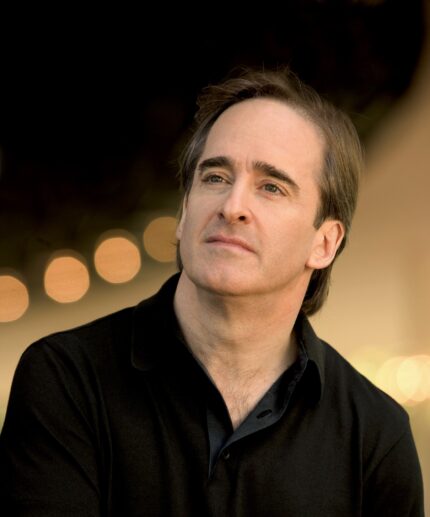

Conlon’s Mahler cycle closes with a powerful, moving Ninth Symphony

When James Conlon took the reins of the Ravinia Festival, he announced two major initiatives: exploring the music of composers persecuted by the Third Reich, and a complete traversal of the symphonies of Gustav Mahler.

Ravinia’s music director has accomplished both tasks in his five-year tenure, and the latter project came to its apparent conclusion Sunday evening with the performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, the Austrian composer’s final completed work in the genre. (In a serendipitous bit of duel summer programming, Carlos Kalmar and the Grant Park Orchestra will tackle the same symphony next month at the Harris Theater.)

Conlon’s chronological survey has received mixed notices, unsurprising for an orchestra with a rich Mahler lineage that has provided memorable interpretations by Haitink, Tennstedt, Abbado, Solti and Levine in recent decades, many of them recorded touchstones. Yet Conlon rose to the challenge of Mahler’s epic Ninth superbly with a powerful, deeply committed and magnificently played performance.

A century after its completion, there is still nothing quite like Mahler’s final symphony. Outwardly traditional in four movements, Mahler explodes expectations with two vast slow movements flanking a pair of faster sections, the 85-minute work pushing the borders of symphonic form to the breaking point.

Like all great works of art, Mahler’s Ninth contains much more than can be revealed in a single or even repeated hearings. Among the striking elements are the symphony’s reaching the limits of Late Romantic form and traditional tonality, and the fin-de-siecle cynicism and anticipation of war in Europe in the distorted waltz rhythms and malign military fanfares. Most of all, there’s a sense of personal tragedy in the composer’s own fateful premonition of his early death. From the opening bars and the sighing two-mote motif from which Mahler builds his vast structure, one can almost feel the composer’s life scrolling past.

Conlon had the full measure of the vast opening Andante, charting the expansive ebb and flow with a taut grip yet the requisite flexibility. Perhaps others have looked into the darkest shadows of the Ninth’s abyss with greater penetration, but the conductor surveyed the music’s range of humor, nostalgia and desolation with great skill and concentration, the Andante’s extended coda beautifully sustained.

Conlon and the CSO brought out the rustic humor of the second movement superbly, seguing from self-satisfied Landler rhythms into increasingly antic and uncontrolled regions. In the ensuing Rondo-Burleske the humor turns harsh and acrid, as the music grows increasingly grotesque and terrifying, the violent brass interjections and acid wind solos given immense character and vehement impact, with only slight consoling balm in the trio’s reminiscence.

The performance was at its finest in the closing Adagio. Conlon’s direction conveyed an expressive yet tempered farewell that firmly conveyed the sense of last things, a stoic acceptance of the harshness and tragedy of life amid a hard-won solace and transcendence of earthly concerns. The playing of the strings in the closing section was extraordinary, the dying away of the final phrases to near inaudibility, masterfully directed by Conlon and rendered with hair-trigger sensitivity by the musicians.

All CSO sections rose to the challenge of this intensely demanding score, with first-class contributions by hornist Dale Clevenger, trumpeter Chris Martin, clarinetist John Bruce Yeh, violist Charles Pikler, cellist John Sharp and concertmaster Robert Chen.

A successful conclusion then to an ambitious series. Perhaps next summer will bring us a postlude with the Tenth Symphony, preferably in Remo Mazzetti’s revised completion of Mahler’s unfinished score.

Posted in Performances