ICE opens season with Italian modernist cool

Time and perspective are admirable filters for separating substance and depth from trendy surface appeal. The kaleidoscopic clothes and billowing hair of the late 1960s today look more lame and dated than the button-down uniformity of the preceding decade they were reacting against.

So too, while musical history is rich with masterworks that baffled early audiences, there are also plenty of avant-garde works embraced by contemporary cognoscenti that have worn less well with the passing decades.

Such thoughts came to mind at the International Contemporary Ensemble’s season opener Friday evening. The alarmingly gifted David Bowlin provided fizzing performances of a trio of late 20th-century Italian works for solo violin at the Museum of Contemporary Photography on Michigan Avenue. How fortunate Chicago is to have such an envelope-pushing ensemble as ICE maintain its base here while presenting series in New York and other cities.

While the evening’s main event was Luigi Nono’s La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura, it was the two shorter works on the first half that provided the most compelling listening.

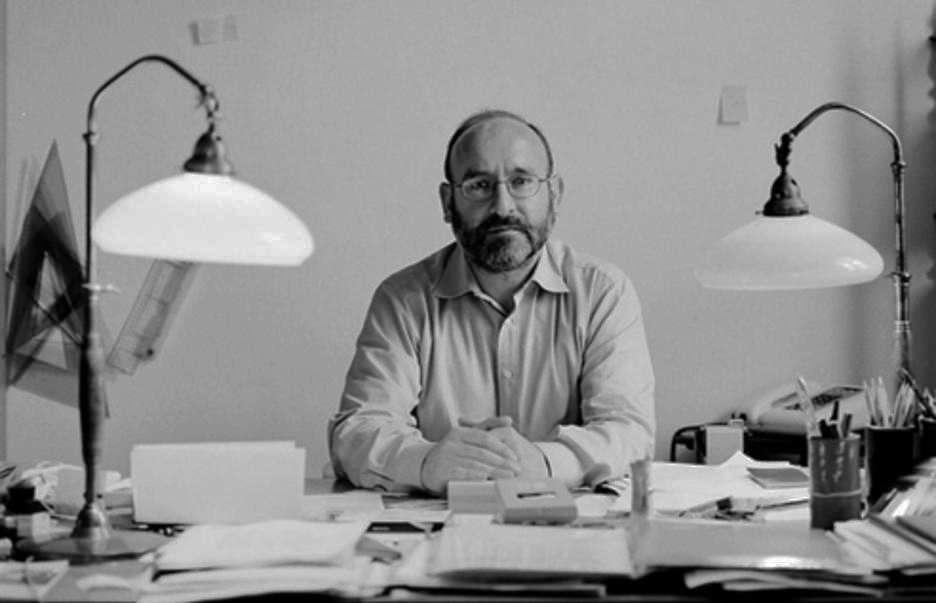

Salvatore Sciarrino—the youngest of the Italian modernist trinity heard Friday and still active at 62—has had the least name recognition historically, but it is Sciarrino’s music that, increasingly, is coming into its own. Bowlin led off the evening with two of Sciarrino’s 6 Capricci for solo violin (1976).

The Capricci take a surface inspiration from those of the Italian’s celebrated forebear, Paganini, but the music goes in a completely opposite direction. Woven entirely in harmonics, inward, hushed and meditative, Sciarrino’s Capricci are the antitheses of Paganini’s blazing fiddle fireworks. Capriccio I and II bear a thematic link to Paganini’s Caprices Nos. 1 and 6, but explore a singular brand of anti-bravura. Capriccio II is especially striking, with its subtly graded hues and barely audible distant avian-like calls. For such intensely concentrated music, there is a sweet, disarming innocence that makes one want to explore the rest of the Capricci and Sciarrino’s prolific chamber output.

Luciano Berio’s Sequenza VIII for violin, composed the same year, was one of a set of thirteen works in the series. Composed over four decades, each sequenza was written for a different instrument, exploiting and often reinventing their sonic capabilities. Here Bach is the clear inspiration, specifically his Partita in D minor for violin.

Berio works a variety of extensive development over the tug between A and B heard at the opening, morphing Baroque counterpoint into an edgy 20th-century polyphony and maintaining interest over the long span. Bowlin here showed greater muscle and an iron bow arm, bringing out the forceful angularity and laser-like articulation of this difficult work with its repeated-note rigor and multi-stopped chords.

It’s one of musical history’s great ironies that the works of the Italian electronic music pioneer and communist Luigi Nono were banned in the culturally reactionary Soviet Union during his lifetime.

Nono’s La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura was positioned as the grand finale of the concert, but unlike the Sciarrino and Berio, now seems very much a work of its time. Completed in 1989, the work is written for live solo violin against multi-tracked prerecorded tape containing disconnected violin notes and improvisations (by Gidon Kremer) as well as noises, indistinct conversations and miscellaneous thumps.

The semi-improvised work calls for the violinist to move between five music stands where massive scores dense with notes await while a sound engineer manipulates the tapes in an attempt to find some sort of ad libitum dialogue between the live and taped forces.

Bowlin provided sterling advocacy and an array of widely terraced dynamics and colors, with engineer Joshua Rubin an equal creative partner. Still, even with the alert, well-prepared performance, Nono’s piece feels dated, gimmicky, and ridiculously extended at three-quarters of an hour. After ten minutes, we get the idea and the ensuing half-hour of alternating violin and electronic fiddle sounds, beeps and thuds soon morphed into the eight-channel musical equivalent of waterboarding.

The International Contemporary Ensemble offers a musical portrait of Kaija Saariaho 8 p.m. Nov. 19 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, with the Finnish composer in attendance. www.iceorg.org.

Posted in Performances