The heart of Glass

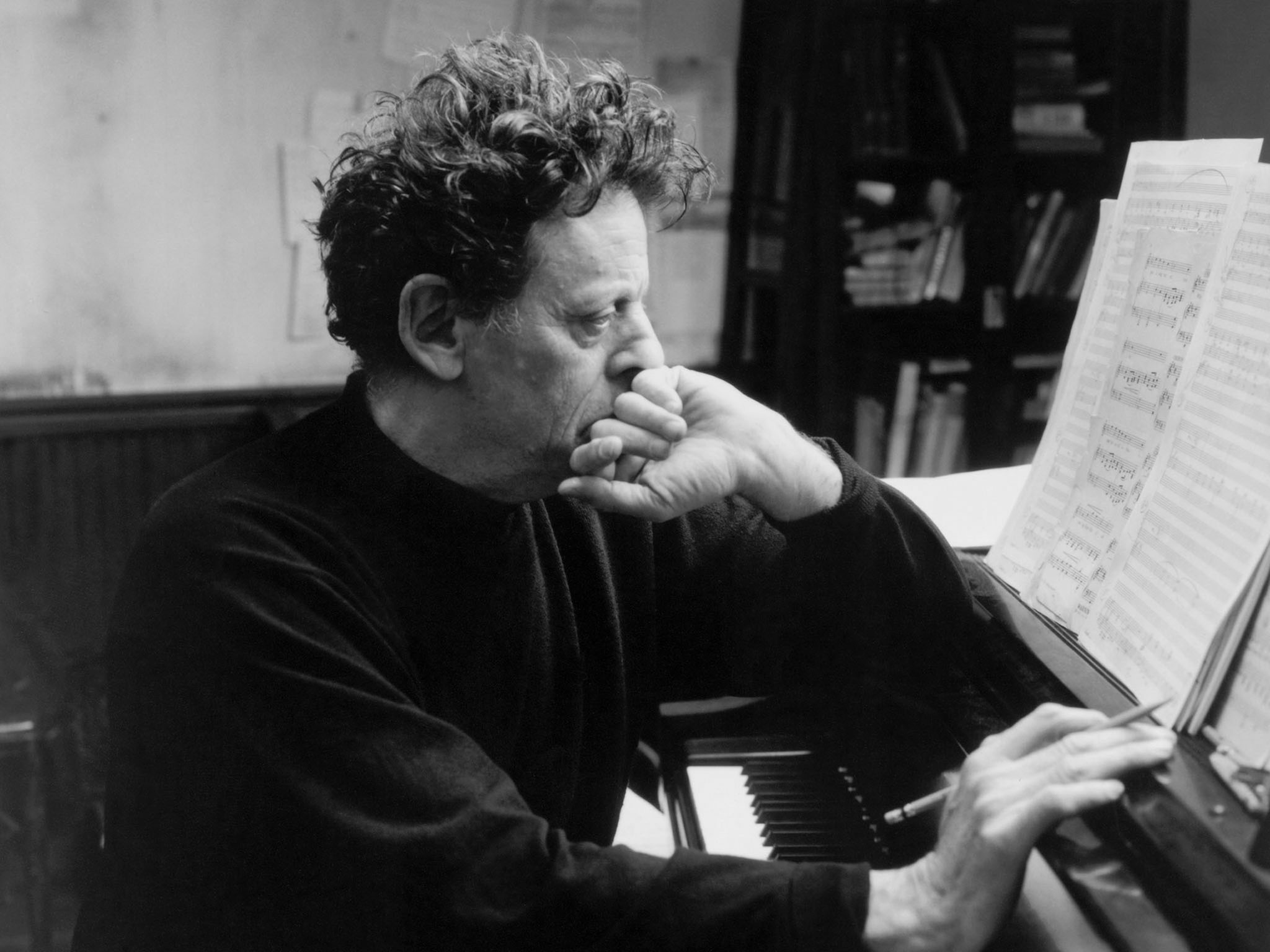

Philip Glass came to Chicago Friday night to perform his music at the Museum of Contemporary Art, an event which prompts the question: Has Philip Glass achieved the status of Old Master yet? Or does his music continue to polarize audiences as it has consistently done throughout his career?

The diverse group at the museum seemed to be of one mind in their enthusiasm for the 73-year-old avant-garde legend. But questions remained about the final stature of the work.

His solo piano recital preceded a staged revival of Dance, a theater piece he scored in 1979 for the choreography of Lucinda Childs enhanced by the filmwork of Sol LeWitt. This dance piece would perhaps be more representative of his strengths as a composer than the one-dimensional piano works, which seemed more like a sketches or reminders of some of his larger works. The real genius of Glass is in his full scores for movies, theater pieces and dances where his deceptively simple sound world underpins and enhances the gestures and emotions of the text at hand. The solo piano format robs the music of some of its rich context as well as its minimal but constantly changing instrumentation.

In addition, the composer is perhaps not the most adroit performer of his own works. One could imagine a fleeter and more technically accurate pair of hands doing better justice to the variety of changes demanded by the scores. Perhaps his finger injury a couple years ago continues to slow him down.

But even though Glass’s piano playing was only just adequate to his needs, there emerged from the ostinatos and arpeggios that mark his style (is it still called Minimalism?), a set of short pieces reflecting inventive takes on the building blocks of the musical experience: rhythm, dynamics, melody, harmony and tonality abstracted and deconstructed and run through the Glassian blender.

The first set, Four Metamorphoses, opened with an atmospheric selection from the obsessive and foreboding soundtrack to The Thin Blue Line, the paranoid 1989 documentary by Errol Morris. That was followed by rarely-heard music from the Kafka Trilogy, first performed in Sao Paulo, Brazil the same year. The tone of this music was unrelentingly dark, reflecting the subject matter, and yet there was a nice range of dynamics and figuration which kept the final results engaging.

This range of elements was elaborated in the meat of the recital, 8 of the 16 Etudes for piano written in 1999, which are exercises in “pure” music and not related to any extrinsic work. Here we have perhaps Glass’s Diabelli or Goldberg Variations. Beginning with a flourish, blocks of music extend out with barely a breath of a pause between sections and with dynamic rhythms and melodic and tonal invention breaking through the seemingly empty repetition of patterns. It is the variety of these elements that keeps the music intellectually interesting. The piano’s tonal range is exploited at both ends of the keyboard, and there are fragments of melody that would be called sentimental in a different context.

Perhaps the main objection to these pieces is that ultimately they have no shape. Without much of a beginning each work unfolds as a linear continuum with successive ups and downs, only coming to an end when Glass has taken his hands off the keyboard and half-turns toward the audience in the time-honored ritual of the veteran recitalist.

As an encore, the composer performed a piece from his first major-label album Glassworks. The lightness and transparency of this early work was a nice chaser to the dark obsessions of the other pieces.

Walking out of the MCA, audience members discussed and some argued over the value of the music we had just heard. The Old Master is still shaking people up.

Posted in Uncategorized

Posted Oct 18, 2009 at 8:17 pm by Pathan K.

I like this very diplomatically expressed criticism of music which is very boring, and which this composer can’t play well himself.

If it gets appreciated, it’s only by those who learned to play piano the same way he did, and who do not try to know better in the world where good music is accessible.

Posted Oct 19, 2009 at 10:14 am by Proman

“one-dimensional piano works… The solo piano format robs the music of some of its rich context as well as its minimal but constantly changing instrumentation.”

Wrong. Glass’ paino works are rich and beatiful, and are a great layer of his ouvre by themselves. I have heard him perfom them in person and I can testify that they are anything but what you are calling them. He also performs them very well because more than anyone else he understands the tempo at which these works are meant to be performed. By calling them one-dimensional you simply prove that you don’t understand Minimalism and show how one-dimensional you are and also

Posted Oct 19, 2009 at 8:11 pm by Steve Glassfan

Glass is not a vituoso pianist, and he does not even play all of the pieces that he has written, as he spends most of the time composing and not practicing piano 24 hours a day. He knows there is way more to his music than just his solo piano concerts. He still plays them because he loves to be in front of his fans. If you want to hear some amazing Glass piano music, try out Les Enfants Terribles (for three pianos)- simply amazing and beautiful. Also check out his new piece, Four Movements for Two Pianos, which was just released on CD.