Chicago Philharmonic offers fitful passion in chamber program

The good news this season is that the Chicago Philharmonic orchestra really is an orchestra again. In 2008-2009, a dire financial deficit forced the Philharmonic to present chamber events to aright their financial ship. Now back on a more secure footing, the orchestra is at full strength this season for three of its four concerts.

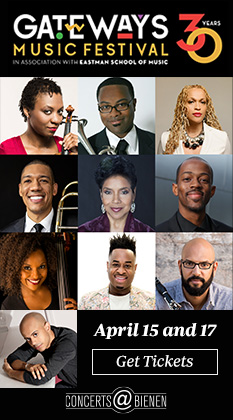

The sole chamber program this season titled “Hungarian Passion” took place Sunday night at Pick-Staiger Hall with orchestra members serving up a chamber chestnut by Brahms and a rarity by Erno von Dohnanyi.

Dohnanyi’s Sextet is a genuine curio. Written in 1935, it is scored for offbeat forces: violin, viola, cello, clarinet, horn and piano. The Sextet shows the Hungarian composer’s admirable craft and undoubted skill in balancing the divergent mix of timbres while deploying material equally among all six players.

Dohnanyi’s style here is a kind of no man’s land—a less astringent Bartok meeting a Brahms without the tunes. A restless, surging opening movement leads to an Intermezzo with a repeated-note lyrical theme that segues into an ominous march-like trio that seems to reflect some of the era’s political clouds on the horizon. A playful third movement with a perky clarinet melody leads into a concluding Allegro vivace giocoso with an infectious syncopated main theme occasionally interrupted by a violin-led Viennese waltz for no apparent reason.

If the preceding movements had more of the finale’s quirky individuality, the Sextet would be a more worthy piece. Even with Dohnanyi’s facility, there is a lack of indelibility to the themes and, often, a rather mundane working out of material, as in the Intermezzo.

No undiscovered masterpiece but give the Chicago Philharmonic players props for presenting this offbeat work. The ensemble provided largely lively and polished advocacy with especially fine contributions by hornist Neil Kimmel.

A long-discovered masterpiece was heard after intermission with Brahms’ celebrated Piano Quartet in G minor. The German composer’s work merits inclusion under the “Hungarian Passion” rubric by virtue of the gypsy-flavored Rondo alla Zingarese finale.

The 19th-century critic who called Brahms’ music “all beer and beard” would have probably enjoyed this performance of this Piano Quartet, which was lightly sprung and refined, some fleeting errant string intonation apart.

Still, this was a conscientious rather than an involving performance and passions—German, Hungarian or otherwise—were fitful at best. There was a decided lightness of being with a lack of heft and muscle, both at the keyboard and in the strings in a big-boned work that needs to be put across with much greater weight and intensity. The Andante showed more responsiveness and the insistent gypsy finale brought some belated fire, mostly from first violinist David Perry. But for the most part, this Brahms felt more like a cautious rehearsal than a finished public performance.

Posted in Performances