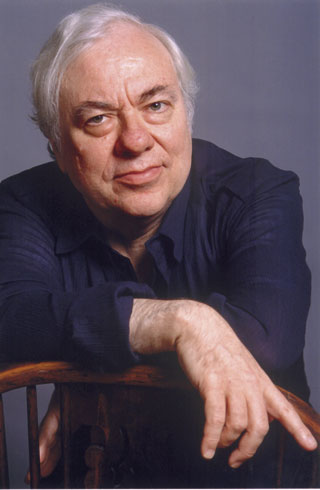

Timeless and individual, Richard Goode’s artistry shines in Bach and Haydn

Audience members almost audibly wince when management steps out for an announcement at the beginning of a recital: is somebody sick or is repertoire that ticketholders were looking forward being dropped from the planned program?

Only at a Richard Goode recital would you get the announcement that a piece had actually been added to Symphony Center’s Sunday afternoon recital.

The supplementary work was Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in G Major (BWV 885) from Book II of The Well-Tempered Clavier, played before the already announced opening Bach set that included the Prelude and Fugue in f-sharp minor (BWV 883) and the Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp Major (BWV 872), all also from Book II of the WTC.

That was a smart call, setting the precedent that would also hold true for the Haydn, with bright, upbeat and brilliant pieces in major keys sandwichiching an introspective, slower piece in a minor key.

Goode’s Bach is a curious hybrid of early music thinking and a more Romantic approach: on one hand, he rarely pedals and allows transparency, form and clarity to dominate features of the music, often taking tempos briskly. Yet repeats are given dynamic contrast and include pianistic shading and colors of vintage 19th-century variety and eccentric rubato that will sometimes nearly grind an established tempo to a halt.

Taken on its own, this was a far more personal interpretation of Bach than is considered acceptable these days, yet given the musicianship and connection to the rest of Goode’s program, he managed to make it work.

How often do you have a chance to hear not one, but three, Haydn sonatas on a single program? This was a bold move, and each were positioned for maximum contrast.

The Sonata in E Major (Hob. XVI:22) and b minor (Hob. XVI: 32) both belong to Haydn’s so-called Middle Period, which in terms of his keyboard sonatas means that he was moving away from the faithful use of classical form that he had established in the early sonatas—-from the limitations of the clavichord and embracing the new fortepiano and its dynamic possibilities, with pieces more demanding, daring and unpredictable.

It was evident that Goode chose Haydn sonatas that show a particular debt to Bach — or at least Goode’s own interpretation of Bach, particularly in terms of how he handled rolling arpeggios — but in the case of the Sonata in C Major (Hob. XVI:50), he also wanted to make Haydn a link to the ardent Romanticism that would be represented on the second half of the program.

Schumann’s Kreisleriana made up the remainder of the planned program, a world that Goode seemed more familiar and comfortable with not only in terms of this being the only piece of the day where he was not reading music, but also in terms of his confidence and swagger.

From the opening notes, Goode literally attacked the instrument like a pianistic alchemist, bringing forth a huge variety of colors and moods. Goode strived to show the enormous debt that Schumann owed to Bach and Haydn, despite such explosion of form and Schumann’s putting the music completely at the service of emotion.

Encores included music by Elizabethan composer William Byrd that consisted of a prologue followed by a lively minuet, as if to show that even Bach had his influences, and a Chopin nocturne that saluted the Chopin bicentennial while also serving as a fitting farewell to an extraordinary afternoon.

Posted in Performances