A quirky Hungarian concerto amid luminous Debussy and Ravel from Boulez and the CSO

It’s unfortunate that this week’s Chicago Symphony Orchestra concerts are such an abbreviated affair with just two performances sandwiched into the Thanksgiving holiday weekend. For, in addition to some stellar Debussy and Ravel from Pierre Boulez and the orchestra, Friday night’s program offered the belated CSO premiere of a significant late-20th century work, with György Ligeti’s Violin Concerto, performed by Robert Chen.

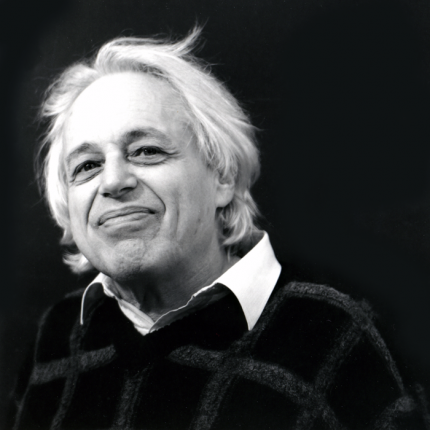

Ligeti wrote some of the most individual and distinctive music of the second half of the 20th century. The Hungarian composer’s Atmosphères and Requiem received unlikely pop-culture status due to their deft usage by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey. And while Ligeti’s paradoxical mix of subversive anarchy and technical precision doesn’t always wear well—his 1970s opera Le Grand Macabre seems very much a work of its time—at its finest Ligeti’s polystylism presents a witty, imaginative approach to timbre, rhythm and scoring that makes for striking if sometimes challenging listening.

Ligeti’s Violin Concerto is a late work, written in 1990 and substantially revised after its premiere with three short sections replacing the original opening movement. From the delicate, barely audible rustle of the violin soloist, we are immediately in the Hungarian’s unsettling sonic landscape, with the opening pages backed by scordatura violin and viola that suggest a maladroit string ensemble unsuccessfully trying to tune up.

Many of Ligeti’s far-flung handprints are here, with microtonal writing, clusters, and a wry grotesquerie amid sudden moments of unexpected lyricism. His quirky musical humor is reflected in the four ocarinas that the wind players are called to double on, and Boulez ensured the hollow piping made its desired impact.

Ligeti’s Violin Concerto may not be one of the great fiddle showpieces of the 20th century, but it’s a significant work in a major composer’s output and received a highly polished and accomplished performance from Robert Chen Friday night.

As one would expect, the CSO concertmaster brought full commitment and technical precision to this tortuous work, and sailed through the extended final cadenza and burst of fireworks with undaunted poise.

But as Christian Tetzlaff and others have demonstrated, there is a firm–if decidedly offbeat—bravura element in this concerto, and I felt that was largely lacking Friday night.

Chen was at his finest in the fleeting expressive passages as in the Passacaglia and the brief Aria, where his pure, silvery tone brought a Bachian serenity to the music, which briefly flowers ino a nostalgic lyricism worthy of Samuel Barber.

But at times the solo playing felt merely conscientious rather than compelling, wanting in personality and a more boldly projected tone. With the soloist’s light-textured timbre set against Boulez’s firm pointing of the uninhibited scoring oddities, the performance often had a concerto grosso feel to it, with Chen’s violin subsumed into the textures of the backing ensemble.

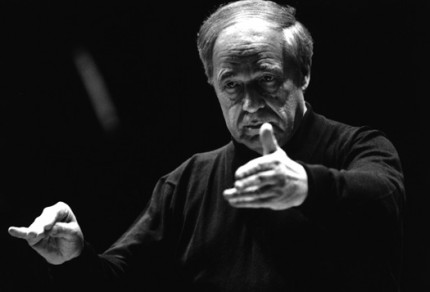

Apart from some moments of metrical rigidity, Boulez made every strange element register and his CSO colleagues—notably percussionist Cynthia Yeh who is kept busy in this work—supplied Chen with intensely focused glove-like support.

The atmospheric Debussy and Ravel works that made up the rest of the program formed a fine contrast to Ligeti’s thorny modernism.

Boulez’s bracing take on Debussy’s La Mer is familiar to Orchestra Hall audiences and Friday’s performance was in the same tradition—firmly detailed and scrupulously balanced with a notably cataclysmic tempest whipped up in the final section.

The nexus in French art between ardent Roman Catholicism and limpid sensuality was the catalyst for The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. Debussy wrote over an hour of incidental music for this oddball hybrid, a dance performance by the celebrated Ida Rubinstein with choreography by Michel Fokine depicting the Christian martyr murdered by Diocletian’s archers. The 1911 premiere proved the worst of both worlds, creating a scandal that never translated into public interest or popular success.

Still, there is worthy music here as shown in the suite of four excerpts, performed Friday in the Andre Caplet arrangements, and Boulez’s lucid objectivism fits this music perfectly. The conductor brought out the spare mystery and elliptical lyricism, eliciting notably transparent and refined playing by the CSO–a tenuous principal horn apart.

Yet as admirable as the Debussy items were Friday, the performance of Ravel’s Ma Mère l’Oye provided the highlight of the evening.

Even by Boulez’s standard in this repertoire, the luminous performance of Ravel’s Mother Goose suite was extraordinary. Rarely will one hear the essence of this timeless music captured so well, with Boulez and the CSO musicians conveying the varied expressive moods of Ravel’s nursery-tale settings. The humor of the contrabassoon in Beauty and the Beast was finely pointed as was the vibrant percussion that brought out the faux chinoiserie of Laideronnette.

But it is the dominant elegant melancholy that imbues much of this music and that element was especially communicative. Scott Hostetler’s mellow English horn solos in Tom Thumb seemed at one with the music, and the radiant, shimmering rendering of the Enchanted Garden finale was gorgeous, with Boulez ensuring the climax was kept properly in scale.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Saturday. cso.org; 312-294-3000.

Posted in Performances