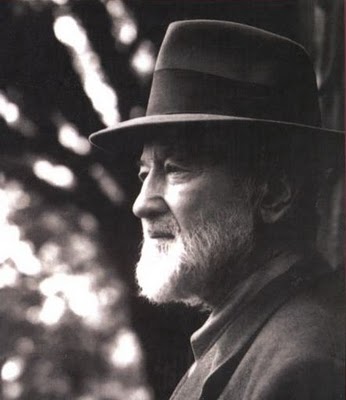

Charles Ives—still radical after all these years, courtesy of the Callisto Ensemble

The Callisto Ensemble opened its season and its year-long exploration of Charles lves on a cold, rainy Monday night at its downtown performance space, the Stradivari Music and Arts Center.

The group could not have picked a more fascinating work to begin that exploration. Ives’ Piano Trio attempts to capture the raucous spirit of the composer’s student days at Yale during the 1890s, and, like so many of Ives’ scores, precise dating is difficult. Ives worked as a highly respected insurance executive by day, only to leave his office to toil by night in virtual obscurity and long neglect as America’s first truly experimental composer.

Ives was indifferent to whether his radical music would appeal to anyone, nor whether it would be performed at all. Elliott Carter, whom Ives had befriended when Carter was a college student, told me that he became dizzy trying to make these scores performable.

It is thought that Ives began work on the Piano Trio as early as 1896 but came back to it on and off in the early years of the new century. As this revelatory performance by the Callisto members (violinist Stefan Hersh, cellist Julian Hersh and guest pianist Paul Hersh) demonstrated, the work still has the power to provoke more than a century later.

The opening Moderato movement begins with piano and cello starting out innocuously enough, expanding into rhythmic cello arpeggios that could almost prefigure Minimalism before a high violin starts to gradually tip the work beyond the fringes of tonality.

The middle movement–titled TSIAJ Presto for “This Scherzo Is A Joke”–pre-figures Bartók with its string effects before it expands into a take-no-prisoners musical brawl said to portray the games and antics of spirited students. Particularly fascinating is the way that Ives mixes snatches of popular tunes of the day into the melee, included My Old Kentucky Home. Rock of Ages emerges as the preferred personification of perceived normality, particularly in the finale, though the quiet, seemingly contemplative calm after-the-storm cadence lets an alternate key have the last laugh.

It would be hard to imagine a greater contrast with Ives than the music of his conservative younger contemporary across the pond, Arnold Bax, who represented a nostalgic culmination of late Romanticism. The British Irishphile was so taken with the beauty, poetry and even the anti-British politics of the Emerald Isle that he took up the pen name of Dermot O’Byrne to write poetry and short stories in addition to his compositions.

Bax’s 1922 Sonata for Viola and Piano spotlights the brand of Neo-Romanticism informed by early 20th century harmonic vocabulary that marked his style. There are shades of Satie and Debussy and even his elder contemporary, Gustav Holst.

Violist Roger Chase made an eloquent case for the work, both verbally and musically, pouring his heart and soul into what otherwise might be fairly mediocre and meandering music. The piece is well-crafted, to be sure, but is overlong and overblown. Paul Hersh provided stellar piano accompaniment that admirably matched Chase’s subtle shifts of mood and tone.

The evening began with a spirited traversal of the Beethoven String Trio, Op. 9, No. 2. The Trio is an early work where we hear Beethoven on his way to finding the voice that would change everything in music and a delightful homage to the posthumously published Mozart Divertimento, K. 563 that inspired it.

Posted in Performances