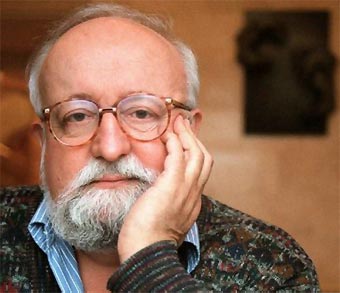

Penderecki to conduct the Grant Park Orchestra this weekend

While most music festivals across the country are content to serve up the standard populist summer fare of Gershwin and Tchaikovsky, the Grant Park Music Festival, once again, is embarked on the repertorial path less taken.

This Friday and Saturday Krzysztof Penderecki, Poland’s greatest living composer, will lead the Grant Park Orchestra in Beethoven’s Eroica symphony and his own Concerto Grosso for Three Cellos and Orchestra. Julie Albers, Kira Kraftzoff and Amit Peled are the soloists.

At an afternoon rehearsal this week, the 77-year-old composer, seated on a high stool, led the Grant Park musicians in a sturdy, firmly projected account of the vast Marcia funebre movement of Beethoven’s symphony, only occasionally stopping for small adjustments and making them laugh at least once with a well-timed aside.

“It’s a very good orchestra,” the soft-spoken, grandfatherly composer said later backstage. “It’s noisy outside though on the street with the cars. The birds are fine. You get used to it after a while.”

Penderecki burst upon the music world in 1960 with his Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. Scored for 52 strings, this powerful, shattering work immediately established Penderecki as one of the world’s most individual young composers with a distinctive sonic landscape of jarring tone clusters, aleatoric techniques and an intensely chromatic “hypertonality” that would continue in densely layered works like Akalasis and Fluorescences.

It’s often commented how Penderecki’s musical style has evolved from an aggressively edgy avant-garde style to a more tonal and approachable idiom. But for the composer it’s less a conscious stylistic turn than a reflection of the seismic changes in his home country and around the globe in the intervening decades.

“The world has changed,” said Penderecki. “This is forty, fifty years ago. How can an artist do the same thing? There are some who do the same thing their whole life, like Chagall. Even as a boy painting in Vitebsk, he was doing almost the same thing.

“No, I am more the type of an artist that is constantly changing. Like Picasso, who is maybe the best example.”

“Those pieces — Threnody, Fluorescences, Polymorphia — they are unique in their technique. I cannot even use the elements because it belongs to the style [of the era].You can’t go back.”

This weekend’s concerts will offer the second local performance of the Concerto Grosso for Three Cellos in four months, following the belated Chicago premiere led by Charles Dutoit with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and three CSO members as soloists. “Of course, it goes back to the form of the Baroque, but my piece is not Baroque,” said Penderecki. “But some elements, some chords, cadenzas, some ways of playing the arpeggios are from the Baroque. But it’s just the joy of writing music. And I was a violinist so for me string instruments are very familiar.”

Penderecki was a close friend and colleague of the most celebrated cellist of the past century, Mstislav Rostropovich, for whom he wrote his Second Cello Concerto, as well as noted German cellist Siegfried Palm, who championed contemporary music in the 1950s and 1960s.

Few solo instruments are suitable for exclusive use in a triple concerto, says the composer. “The cello is the perfect instrument for this, because it has a scale of six, even seven octaves. It is incredible what you can write for cello.”

This week’s performances mark the composer’s first appearance in Chicago in over a decade since he led the CSO in his Symphony No. 7, Seven Gates of Jerusalem in 2000. One would think that coordinating his triple concerto would be a challenge on Grant Park’s short rehearsal schedule, but the composer says that is not the case.

“I have just one rehearsal with the soloists,” said Penderecki “Which is fine. This piece is much easier than the Beethoven.

“Because the Eroica has such a tradition. Each note is in a tradition. There is no way you can do the Eroica other ways with different tempi. The responsibility is much bigger doing other music than mine, because who knows my music that much? Only I know it,” he says with a quiet chuckle.

Penderecki disputes the contention, often read in program annotations, that he had an artistic block for several years in the 1970s when his creative output was sharply curtailed. Rather, he says, it was that like Mahler, his podium commitments pushed his creative work in the background. (Penderecki is currently artistic director of the Sinfonia Varsovia orchestra in Warsaw, which he regularly conducts every season.)

“I never stopped composing completely,” he said. “Sometime for six months or so, because I was busy conducting. It’s true sometimes conducting takes up my time. But I do it [primarily] to perform my music.”

One little-known aspect of the composer’s output is how often his music has been effectively mined by celebrated directors in films, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining most extensively (music from Utrenja, Kanon Paschy, The Awakening of Jacob, Polymorphia, De Natura Sonoris Nos. 1 and 2). Penderecki’s music was also utilized in The Exorcist (Polymorphia) as well as Wild at Heart, Inland Empire, Fearless (Polymorphia again) and Shutter Island (Symphony No. 3 and Fluorescences).

The composer’s strong Roman Catholic faith imbues much of his music. The St. Luke Passion was courageously written and performed in 1965 when religious works were not encouraged in communist Poland, and that spiritual element is manifest as well in Utrenja, and perhaps most famously, the Polish Requiem. That expansive choral work began with the Lacrimosa of 1980, written in tribute on the tenth anniversary of the deaths of the shipyard workers at Gdansk.

Yet his humanistic art has also drawn from other religions, notably Judaism in Seven Gates of Jerusalem, and his recently completed Kaddish, which will be premiered in New York next season. He is also working on his fifth opera, a setting of Racine’s Phaedra to be debuted by Wroclaw Opera.

“I have many texts that I have prepared for this opera,” said the composer. “But I have to live another fifty years at least to be able to do it.”

“I am always planning more than I am really able to do,” he says with a smile. “This forces me to get up and work rather than waiting for inspiration to come.”

Krzysztof Penderecki conducts the Grant Park Orchestra in his Concerto Grosso for Three Cellos and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 Eroica, 6:30 p.m. Friday and 7:30 p.m. Saturday at the Pritzker Pavilion. Admission is free. grantparkmusicfestival.com

Posted in Uncategorized