Muti and CSO have got a little Liszt

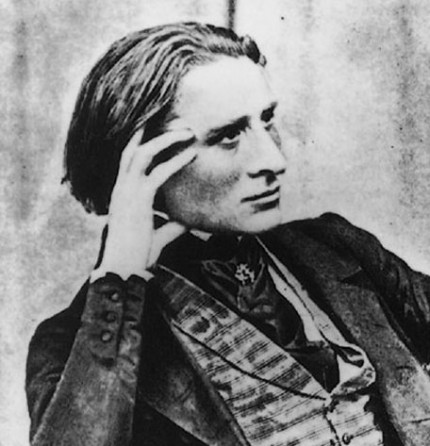

For the second week of Riccardo Muti’s second season, the Italian conductor and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra presented a Largely Liszt program marking next month’s 200th anniversary of the Hungarian composer’s birth.

Friday night’s program offered the best of Liszt and the worst of Liszt with what is arguably one of his most successful works and also one of his least — if most popular — essays in superficial keyboard fireworks.

While the Sonata in B minor remains Liszt’s masterwork, his Faust Symphony is clearly his most accomplished work for orchestra. Liszt was obsessed with Goethe’s tale and, inspired by Berlioz’s treatment in his Damnation of Faust, created a tripartite symphony with three movements representing Faust, Gretchen and Mephistopheles, later adding a finale for tenor and male chorus.

At 73 minutes, the Faust Symphony has its longueurs and discursive moments. But it remains one of the composer’s most finished works, scored with great skill and delicacy, and often audacious, as with the acidulous deconstruction of Faust’s themes in the Mephistopheles movement.

Riccardo Muti’s brand of intensely focused and expressively detailed advocacy could hardly have made a stronger case for Liszt’s symphony, drawing responsive first-class playing from the orchestra. The CSO music director held together the episodic 30-minute Faust movement with unerring skill, fluently melding the disparate themes together while maintaining a firm puse and forward momentum.

In the middle movement, depicting the tragic heroine Gretchen, the playing had a touching ars antiche quality in the nostalgic theme for oboe and viola, Muti shaping the long-lying phrases and drawing rarefied pianissimos.

The sardonic devilry of the finale was aptly rambunctious, setting the scene for the choral coda. The men of the CSO Chorus entered slowly and theatrically as Liszt requests — though a bit late to get into position Friday — and delivered a robust and clarion reading of the Goethe passage, with pealing organ and orchestra in full cry. Eric Cutler’s tenor is a bit thin on top but he provided worthy singing with the chorus in his brief role. Too bad some cretinous audience member’s jangling cell phone ruined the hushed entrance of the choir.

The CSO covered themselves in glory in this performance with superbly expressive solo work by oboist Eugene Izotov, flutist Mathieu Dufour, violist Charles Pikler, hornist Dale Clevenger, and harpist Sarah Bullen.

It’s been 25 years since Michele Campanella’s only previous CSO performance when he tackled the sprawling Busoni Piano Concerto (Sir Charles Mackerras conducted). In two appearances, the Italian pianist has spanned the genre, going from the longest piano concerto in the repertoire to the shortest with the single-movement Liszt First Concerto.

With its banal themes, heavy-handed scoring and bursts of keyboard flash, it’s hard to account for how a work of such awe-inspiring crassness stays in the regular repertoire. The principal virtue of Liszt’s showpiece, written for his own show-offy concerts with orchestra, is its relative brevity.

Campanella’s bona fides as a Liszt advocate were clear in the refined expression he brought to the fleeting lyrical moments and the jaunty vivacity of his playing in the final section.

The veteran pianist was less successful in the work’s bravura passages. With a few digital slips early on, the soloist sounded dexterous and cautious in a work that requires more explosive virtuosity to make an impact. There was no lack of either in the high-powered accompaniment of his compatriot Muti and the orchestra.

The concert led off with the Huldigungsmarsch, composed by Wagner for his adoring and generous patron, King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

If not quite as much of a dog of a piece as Wagner’s Centennial March, heard on the same stage a year ago, the German composer’s tribute to his sovereign still falls under what could be called Muti’s Not-So-Great Works by Great Composers series. The CSO music director drew a spirited reading with notable brilliance and tonal refinement while deftly tamping down the unhealthy vulgarity.

With Robert Chen ailing, the CSO’s new associate concertmaster Stephanie Jeong moved into the first chair Friday with great confidence and aplomb. Jeong led the section with highly energized playing and brought sweet-toned expression to her violin solos in the Gretchen movement of the Liszt symphony.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Saturday and 7:30 p.m. Tuesday. cso.org; 312-294-3000.

Posted in Performances