Muti, CSO and Chorus provide expert advocacy for Cherubini

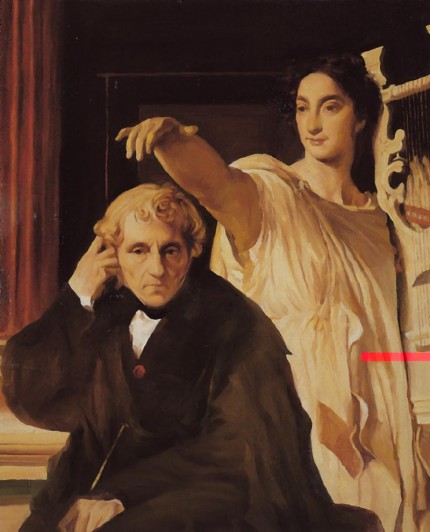

Riccardo Muti has long been a tireless advocate for the music of his compatriot composers, and perhaps none more than Luigi Cherubini. The conductor has performed and recorded such esoterica as Cherubini’s opera Lodoiska as well as nearly all of the composer’s extant masses (a bargain in a reissued EMI box set).

For the final week of his spring residency, Muti led the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus Thursday night in Cherubini’s Requiem in C minor, the work’s first CSO outing since Carlo Maria Giulini last conducted it here in 1967.

In a program note, Muti nails his flag to the mast for Cherubini, noting that the early 19th-century Italian was greatly admired by Beethoven and Schumann, “a musician for musicians” who wrote works of great integrity and, often, austerity, avoiding flashy theatrics and showiness for its own sake.

To be sure, there are distinctive, forward-looking moments in the 1816 Requiem, written to mark the anniversary of the death of Louis XVI. In the opening Introit and Kyrie violins and high winds are silent and the dark scoring sets the somber mood directly and effectively. Cherubini’s taut rhythmic underpinning and contrapuntal skill are manifest throughout. The cumulative mounting tension in the Dies Irae is ratcheted up skillfully and the big choral fugues of the Offertory—which takes up nearly a third of the 44-minute work—are undeniably dazzling.

Still, one can’t help the nagging feeling that calling the Requiem in C minor a neglected masterpiece is somewhat overstating the case. The thunderous gong stroke at the opening of the Dies Irae feels a bit cheesy and, for all the composer’s craft and discipline, the Requiem has its rhetorical moments (the opening of the Sanctus) and longueurs. Too often the music feels cool and calculated, built on architectural externals rather than touching the heart or plumbing a deeper vein of spirituality.

That said, no conductor is a truer believer in Cherubini than Riccardo Muti and Thursday’s committed and incendiary performance by Muti and the CSO and Chorus nearly succeeded in lifting the work out of the second rank. The big choral fugues had explosive power while maintaining striking clarity. Muti repeatedly underlined the imaginative writing as with the sudden dynamic drops of the Lacrimosa dies illa. The alternating dynamic of the closing Agnus Dei can become repetitive but the remarkable degree of calibrated sonic contrast and concentration Muti achieved with his forces in the coda’s long decrescendo was as remarkable a piece of conducting as anything in the actual score.

Under Duain Wolfe the singers of the CSO Chorus provided forceful, highly polished and often thrilling vocalism in the fugal moments. The sopranos were particularly inspired—pure-toned and secure in the mercilessly exposed writing of the Pie Jesu.

The first half of the program effectively set the scene for the Cherubini with two somber, rarely heard choral works by Brahms and Schoenberg.

Brahms’ Schickalslied is rarely encountered today, even with an opening theme for strings that is among the composer’s most beguiling inspirations. Brahms agonized over how to end his setting of Frederick Holderlein’s poem Hyperion, eventually deciding to reprise the opening material to avoid ending on the poet’s intended downbeat note.

The “Song of Destiny” remains an awkward occasional piece not heard downtown in over half a century. Still Muti directed a refined and expressive performance with quite gorgeous string playing and warm-toned yet nuanced choral singing, the coda suffused with a warm benedictory glow.

Less successful is Schoenberg’s Kol Nidre. The polar opposite of Max Bruch’s popular setting for cello and orchestra, the 18-minute work is neither fish nor fowl with a kind of sprechstimme narrator acting as rabbi engaged in a dialogue with the chorus/congregation.

Schoenberg power-washes Bruch’s warm-toned pieties without ever offering anything quite as compelling in its place. For a composer who prized logic and clarity, the writing for chorus and orchestra grows awfully congested and cacophonous.

That said, Schoenberg’s Kol Nidre made an intriguing if decidedly offbeat morsel, heard here in its first CSO performance. Tenor Alberto Mizrahi, hazzan of Chicago’s Anshe Emet Synagogue, was a fine idiomatic presence in the mostly spoken rabbi role and the chorus sang with implacable Biblical power under Muti’s direction.

The program will be repeated 1:30 p.m. Friday and 8 p.m. Saturday. cso.org; 312-394-3000.

Posted in Performances

Posted Mar 16, 2012 at 4:28 pm by martha faulhaber

I rhought the cherubini was a masterpiece of great spiritual depth and the kolnidre was great too. mlf