San Francisco Opera serves up a brilliant staging of Adams’ problematic “Nixon in China”

SAN FRANCISCO. In San Francisco Opera’s current production of John Adams’ Nixon in China, as the doctrinaire Madame Mao closes her showpiece aria singing “I speak according to the book,” she stands, holding the Red Book aloft, atop a large pile of dead bodies, a devastating visual of the carnage wrought by the communist regime upon its own people.

The production, which runs through July 3, is chock full of brilliant theatrical inspirations like that, with the direction by Michael Cavanagh and eye-popping sets by Erhard Rom amplifying, and, in many instances, elevating and improving Adams’ celebrated opera.

It was David Gockley who was the prime mover in commissioning John Adams’ first opera, presenting the world premiere of Nixon in China in 1987 when he was general director of Houston Grand Opera. It is fitting then that Gockley, current SFO general director, is marking the work’s 25th anniversary by bringing Nixon in China to the city by the bay for its company debut.

For its most enthusiastic advocates, modern American opera began a quarter-century ago with Nixon in China. The opera established Adams’ credentials as a viable composer for the stage as well as the concert hall, and the composer’s music for Nixon remains among his finest achievements.

The propulsive energy and rhythmic cunning of the score is inimitable and exhilarating, the bracing range of shifting instrumental colors distinctive, with four saxophones added to the ensemble. The opera offers breakout solo arias for all five principal characters, with music that frequently rises to surprising lyrical heights. There are few moments more thrilling in all of American opera than the banquet scene that closes Act 1. Friday night at War Memorial Opera House as the toasts and speeches continue, and the Chinese and American officials get mildly inebriated, the inexorable acceleration of the orchestra, principals and large chorus built to a climax of Wagnerian proportions set off by the composer’s rock-edged contrapuntal churning.

And yet 25 years after its premiere, for all its audacity and considerable musical virtues, Nixon in China remains an uneven and fundamentally unsatisfying work. Despite the critical success with which his stage works have often found favor, Adams has never seemed to find collaborators as gifted as himself. There is a lack of depth and often a sophomoric banality to the work of librettist Alice Goodman and Adams’ inexplicably favored creative partner, the overrated Peter Sellars (director and librettist on Doctor Atomic). Even when Adams’ music soars in Nixon, Goodman’s chaotic libretto keeps the action earthbound, with its mundane stream-of-consciousness and leaden, syntactically tortuous purple prose.

The libretto has its humorous moments, but too often adopts a snide, superior stance and, as a result, the opera, as a whole, never rises above a prevailing mood of wry irreverence. The schizoid final act is particularly problematic, veering abruptly and unconvincingly from broad Saturday Night Live-like satire to the concluding mood of weighty melancholy. The menacing Madame Mao suddenly says coaxingly to the orchestra, “Hit it boys!” and enlists Mao for a twirl, saying, referring to the Nixons, “We’ll teach these motherfuckers how to dance.”A few minutes later when the opera closes in an extended slow ensemble scene, despite the beauty of Adams’ luminous music, the attempt at a quietly resonant coda fails because the interior nostalgia and unsettled wistfulness don’t cohere with the irony and lack of expressive sincerity in the preceding three hours.

Even with Adams’ terrific music, Nixon in China remains a disconnected series of episodic historical vignettes lacking unity and gravitas and ultimately failing to achieve the higher, deeper qualities it so arduously strives to reach.

Also it’s still hard to overlook the absence of any but the most oblique reference to the dark history of the Chinese regime in Nixon in China. Adams and Goodman have always stated that the opera is a more impressionistic look at the interior thoughts of these famous personages than a historical treatise. No one ever expected a didactic examination of communist pogroms and the Cultural Revolution, but with millions of Chinese murdered under one of the worst tyrannies in history, the fact that these events go unmentioned is not an insignificant fault. Granted, the Chinese officials occasionally turn reflective with a kind of inchoate dissatisfaction, though it seems to come more from a failure to realize the goals of the revolution than any regret for the countless, unmentioned victims of their regime.

Certainly, the opera is unlikely to receive such a successful mounting as this with a first-class cast and relentlessly inventive production. All the principals and eight members of the chorus are amplified, in accordance with Adams’ wishes, which effectively means a large asterisk attached to comments on the singers.

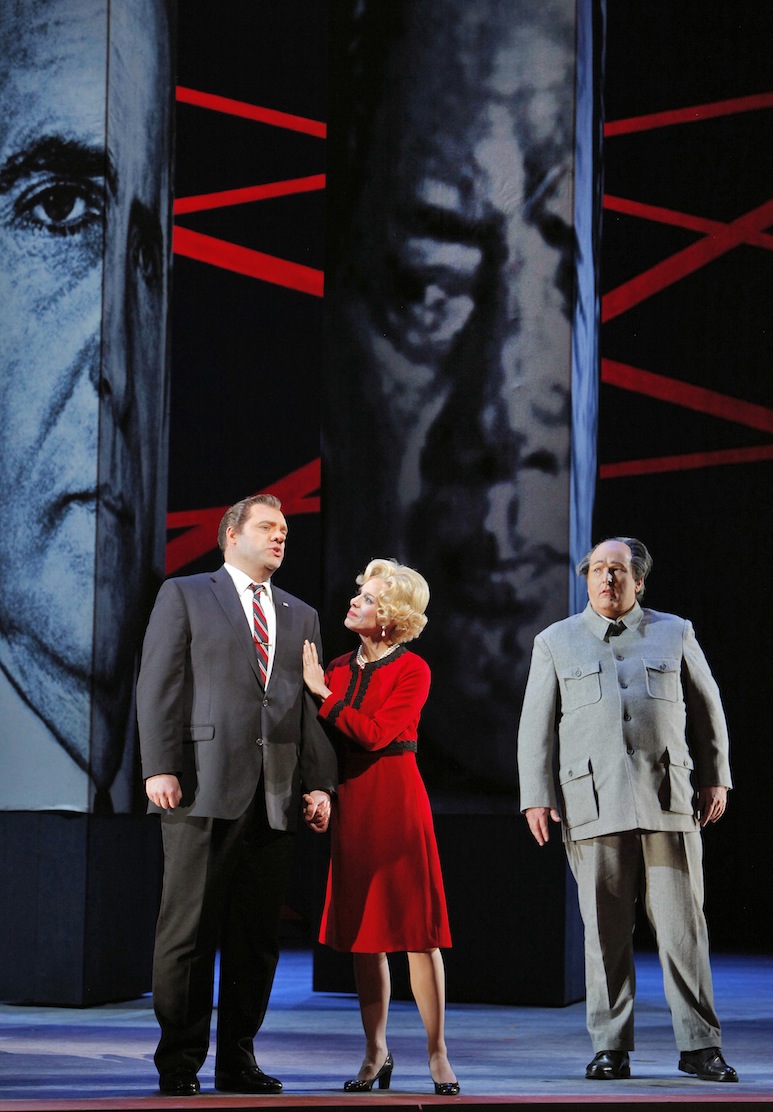

Brian Mulligan made a superb company debut as Richard Nixon. With a prosthetic proboscis, booming baritone, and fine articulative clarity, Mulligan delivered an energetic News has a kind of mystery and sang impressively throughout. The singer captured the president’s awkward physicality while deftly avoiding caricature, and conveyed the public politician as well as the brooding private Nixon.

The opera’s slighting treatment of Pat Nixon offers even less opportunity but Maria Kanyova brought a bright, flexible soprano and surprising depth to her character. Her expressive rendition of This is prophetic proved a highlight Friday, strikingly set against a massive video image of herself, positioned Patton-like, in front of a waving American flag.

Much like the 1972 summit, this production is almost overwhelmed by Mao Tse-Tung. Simon O’Neill’s huge Wagnerian voice belied the supposedly frail party chairman and the New Zealand tenor brought powerful impact to Mao’s philosophic epigrams, his inveighing against capitalism filling the vast house.

As Chiang Ch’ing, Hye Jung Lee delivered a quite sensational performance as Madame Mao. The young Korean soprano brought a scary edge to her showpiece aria, I am the wife of Mao Tse-Tung, handled the coloratura flights with great flair, and sang with pure, radiant tone in the lyrical passages of Act 3.

In make-up, Chen-Ye Yuan could almost pass for Chou En-lai’s brother. The Chinese baritone displayed an ample voice and unfailing tonal elegance, his dignified authority painting a precisely drawn portrait of the conflicted Chinese premier.

Henry Kissinger gets the worst of it in this opera, doubling not only as Nixon’s calculating secretary of state, but as the sadistic tormenter in the Red Detachment of Women ballet (“Doesn’t that look like you know who?” Pat Nixon wonders). Patrick Carfizzi brought a sonorous bass-baritone to the role of Kissinger and lascivious relish to his alter ego menacing the comely proletarian victim.

Ginger Costa-Jackson, Buffy Baggott and Nicole Birkland showed apt unsmiling efficiency as well as strong voices as the echoing chorus of Mao’s secretaries. As Wu Ching-Hua, Chiharu Shibata provided graceful and elegant movement as the heroine of the ballet.

Adams’ music was given fizzing and dynamic advocacy by the San Francisco Opera Orchestra under conductor Lawrence Renes. At times in Act 1 Renes could have balanced the busy elements a bit better—and/or the electronics needed some adjusting.

Director Cavanagh, who previously helmed this Vancouver Opera production in Canada and Kansas City, was most impressive, blocking the often chaotic or static action skillfully, and only occasionally descending into camp silliness as with Nixon and Kissinger cavorting about in little dances.

Erhard Rom’s imaginative production seamlessly blended film projections with the live action. The opera opens with a stunning visual, zooming in from far away to a single window of Air Force One in the clouds where, in real time, Mulligan as Nixon peers out, before zooming out again as the plane peels away. Rom’s sets throughout were brilliant and eye-catching, enhanced by Parvin Mirhady’s historically informed period costumes.

Nixon in China will be repeated 8 p.m. Tuesday and Saturday and 7:30 p.m. July 3. sfopera.com; 415-864-3330.

Posted in Performances