Isserlis and Gerstein bring the heat on a chilly Chicago night

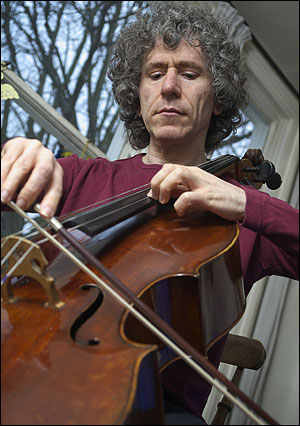

On the coldest night of this meteorologically bizarre winter, Steven Isserlis and Kirill Gerstein provided ample heat Friday night in Hyde Park.

The University of Chicago Presents program marked the return of the British cellist to Mandel Hall, and with both Brahms cello sonatas as the main attraction—and the extraordinarily gifted Gerstein as keyboard partner—even the freezing 3-degree temperature didn’t prevent a large crowd from coming out and packing the refurbished venue.

Two decades separate Brahms’ two sonatas for cello and piano. The Cello Sonata No. 1 in E minor, written at age 22, was Brahms’ first completed sonata for two instruments. While there are moments of awkwardness and a stilted academic formality surfaces in some of the writing, the mature composer to come is evident in the melodic contours and dark sonority with much of the cello music lying in the instrument’s lower register.

Isserlis’s bristling intensity was responsive to the youthful vitality while also bringing a yearning lyricism to the interior pages. The two men showed a sure feel for the fantasy element and Brahmsian ebb and flow in the expansive opening Allegro. The central Allegretto was aptly playful and lightly inflected while the impassioned finale was put across with imposing stormy intensity, rounded off with a burst of velocity at the coda. Gerstein’s playing was consistently insightful and alert, though the pianist was a bit too deferential to his cellist colleague, keeping his dynamics down a notch too far at times where the keyboard part needed to be highlighted more strongly.

The Cello Sonata No. 2 in F major is a work of Brahms’ full maturity, showing greater assurance and individuality, with the composer’s vein of lyricism and headlong energy to the fore here with vivid, at times jarring contrasts in four movements.

With his animated facial expressions, Isserlis showed intense engagement with the music throughout. He and Gerstein displayed a spirited response to the opening movement and were fully in synch with the rhapsodic style of the music, drawing out the lyric episodes without sacrificing cohesion and forward momentum. The lovely Adagio brought playing of child-like delicacy from both men, while the ensuing scherzo-like movement was played with sharp rhythmic vitality. Isserlis and Gerstein were close partners in the finale, charting the movement from easy-going and relaxed to the assertive and impassioned expression of the coda.

Isserlis made his recording debut 21 years ago with the Brahms sonatas and his idiomatic touch was superb throughout. One rarely encounters a keyboard duo partner on the level of Gerstein for a featured string artist, or hears the piano part of these sonatas played with the degree of imagination and poetic touch that Gerstein brought to this music. Even in a supporting role, Friday’s concert further burnished the Gilmore Award winner’s reputation as one of the leading pianists of our day.

Four well-chosen rarities nicely prefaced each sonata.

Bartok’s Rhapsody No. 1 was written for violinist Joseph Szigeti but even before the first performance, Bartok arranged it for cello as well. Isserlis fairly attacked the pungent folk accents and tart Magyar harmonies, with playing that would have seemed a bit wild if the playing was not so accurate and precisely focused.

Without a pause, Isserlis and Gerstein segued so artfully from the Bartok into Busoni’s Kultaselle that an inattentive listener might have wondered if this was some new extended edition of the Rhapsody. Busoni’s “Ten Short Variations on a Finnish Folksong” is not quite a trifle with the varied iterations cleverly wrought. Isserlis and Gerstein displayed the right playful touch as well as deftly assaying the bravura demands with light-fingered virtuosity, though the piece makes one appreciate the real Brahms even more than Busoni’s imitative and less distinctive brand of Late Romanticism.

Two Liszt miniatures served as a fine canvas for Isserlis’s range of half-tones, the cellist distilling the Romance Oubilee with an affecting vein of nocturnal melancholy. Die Zelle in Nonnenwerth was especially lovely, with the coda rendered by Isserlis on a silvery thread of barely audible tone.

After an enthusiastic ovation and three curtain calls, Isserlis showed his engaging personality and wit at the end of the program before an encore. The cellist thanked the audience for being so quiet and attentive in January with so little coughing. A woman in the front row said “Solti trained us,” which led Isserlis to launch into an amusing anecdote about performing with the CSO’s former music director in Chicago as a young man. He also apologized for having to continually adjust his endpin throughout the evening, wryly noting that his 287-year-old Stradivarius (Marquis de Corberon [Nelsova]) handled the cold weather better than the ten-year old piece of metal.

Isserlis and Gerstein closed the evening with a hushed and beautifully floated arrangement of Schubert’s song Nacht und Träume, rendered with a glowing intimacy that left the assembled fortified to emerge into the chill winter air.

The next event in the University of Chicago Presents series is harpsicordist Kristian Bezuidenhout 7:30 p.m. February 8. chicagopresents.uchicago.edu; 773-702-2787.

Posted in Performances