Chicago Philharmonic offers a fine mixed lineup for strings and winds

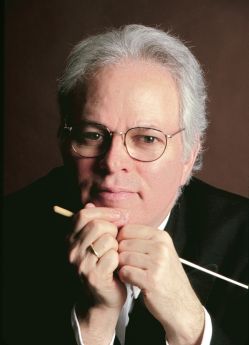

The Chicago Philharmonic under guest conductor Joel Smirnoff was in good form for their Sunday afternoon performance at the Music Institute’s Nichols Hall in Evanston.

The opening work was the brief Reverie et Caprice for violin and orchestra from 1841, a knock-off by Hector Berlioz, who took a discarded aria from his opera Benvenuto Cellini and turned it into an eight-minute violin showpiece for occasional use.

The mini-concerto was masterfully handled by the Philharmonic’s concertmaster, David Perry, who dug into the rich tone of his instrument to provide quicksilver virtuosity and songlike interludes that flashed by in rapid succession.

Unlike the patched-together Berlioz, Richard Strauss’ Metamorphosen, the composer’s tragic masterpiece from 1945, is a fully integrated work for a group of 23 stringed instruments with an emotionally intense core and a complex overarching structure. It begins at a low level but pushes inevitably and broadly forward. A succession of rising and falling climactic sections are held together by an insistent rhythmic impulse.

Under Smirnoff’s cool but committed hand the work swelled and dwindled gracefully and the austere melodic line flowed into surges of tonality. A long middle section was more agitated, constantly trending downward but never becoming mired in the depths. The beautiful violin solos, handled elegantly by Robert Hanford, added to the orchestral texture.

After a pause the music returns to the opening tempo and the last five minutes of the piece are richly expressive but still on a downward spiral towards a dark and somber ending. The concluding bars were effectively extended by the sensitive and admirably controlled Philharmonic string players.

The final work of the afternoon was Brahms’ youthful approach to symphonic form, his Serenade No. 2, written in 1859. Rather than an cohesive orchestral work, the piece is a succession of variously-scored short pieces each one of which offers musical rewards on a smaller scale, with the composer’s rich melodic inspiration providing the glue that holds the 30-minute experience together.

The Philharmonic players were a bit tentative in spots and the overall effect was a bit less elegant than might have been desired, but Smirnoff’s pacing was fine and there were many felicities throughout the performance.

The first movement, marked Allegro moderato, was mellow with a light touch in the winds and a gentle ending. The Scherzo was brisk and galloping, while the Adagio non troppo provided fine opportunities for the lower strings to fill the live space of Nichols Hall with their warm tones.

The Quasi menuetto was performed with a tipsy humor and the whole piece was wrapped up with a brisk and melodic Rondo allegro which showed off the Philharmonic’s excellent ensemble work. The ending was bright and cheery with shrill piccolo trills embellishing the texture in a playful mode.

Posted in Performances