Akiho’s mesmerizing work the highlight of MusicNOW program

The second MusicNOW program of the season served up one of the most compelling solo performances of the year, amid three other works that included a Mason Bates premiere.

Music for solo prepared piano seems to have gone the way of Nehru jackets over the last few decades—perhaps a victim of too many such works centered on mere sonic effects and gimmickry.

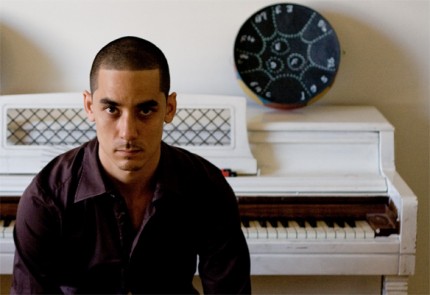

Monday night’s concert at the Harris Theater opened with Vick(i/y) by Andy Akiho. This remarkable 2008 work brings the prepared piano back to its roots, as an unorthodox tool to make music, not as a sound effects sampler or a quirky and “edgy” end in itself.

Inspired by two friends named Vicky, the work is palindromic in structure. Standard piano notes and prepared sounds are set in contrast, and the metallic chords and timbral washes seem to reflect Akiho’s background as a steel pan player. Spaced single notes in the piano toll and fade over the bristling, steel-brush counterpoint. The music grows faster and more aggressive at times but the overall expression is one of stark and calm simplicity.

Monday night’s performance by Winston Choi was mesmerizing. The pianist drew a remarkable, finely terraced array of hues and dynamics from the keyboard, prepared notes and the instrument’s strings—conjuring an atmosphere of rapt concentration and nobility with a hushed pointillist delicacy.

David Lang’s these broken wings was heard just this past summer at Ravinia by the work’s dedicatee ensemble, eighth blackbird. On Monday night, Lang’s offbeat sextet was played by blackbird flutist Tim Munro, Choi, and CSO members, percussionist Cynthia Yeh, violinist Yuan-Qing Yu, cellist Kenneth Olsen and clarinetist J. Lawrie Bloom.

The performance was a well-played one with fine unity (Yu, Olsen, Bloom and Choi collaborate regularly as the Civitas Ensemble). The post-Minimalist drive of the outer movements went with fine vigor and nimble articulation by Choi. The central movement was eerie and effective with the sense of calm unease punctuated by the jarring crash of chains and other heavy objects dropped ad libitum by the players.

Unfortunately, whoever was responsible for the electronic mix dropped the ball as well, with the balance favoring piano and percussion to the extent of making the four other players fitfully inaudible.

Another electronic foulup happened shortly thereafter with composer Edgar Guzman’s video intro to his Prometeo y Epimeteo falling victim to errant technology. The electrical fail was not all bad, however, since it allowed Tim Munro to give his own charmingly personal take on this work for amplified flute and electronics.

“This is the most exhausting piece I’ve ever had to play,” said the English flutist, and it certainly sounded like it, with Munro called upon to toss off a series of effects, noises, bravura riffs and other disparate sounds, emitting a deafening primal scream at the end.

Munro is a greatly gifted musician and attacked the myriad complexities as if his life hung in the balance. Unfortunately, Guzman’s work was the outright clinker of the evening, and proved equally exhausting for the listener, with its lack of substance and noisy farrago of screeches feeling a lot longer than eight minutes.

The evening closed with Carbide & Carbon by CSO co-composer-in-residence Mason Bates, presented in its world premiere.

Scored for eight cellos, the work is a loose homage of sorts to Bates’ favorite Chicago structure, Daniel Burnham’s Carbide and Carbon Building (230. N. Michigan Ave., and currently the home of the Hard Rock Hotel). In the composer’s words, “the ‘carbon’ refers to the duplicating material that jumps from player to player, and the ‘carbide’ conjures the work’s industrial-age energy.”

Despite the composer’s stating that he was inspired by the challenge of writing for an all-cello ensemble (Villa-Lobos’ Bachiana brasilieras the clear scoring inspiration), the unique sonorities and potential of the all-cello forces are not really explored.

Rather, Carbide & Carbon is cast in Bates’ patented style of user-friendly approachability—with up-tempo energy and syncopated riffs batted back and forth, a slower middle section with a lyrical solo line (taken by Kenneth Olsen) set against pizzicato accompaniment, and a driving, sharply rhythmic finale.

It’s fluently written and attractive enough but we’ve heard this song before. Conductor Edwin Outwater imposed more structural cohesion than discipline with some surprisingly scrappy playing and pitchy intonation throughout the performance.

Posted in Performances