Bruckner’s music not a political issue for Mehta, Israel Philharmonic

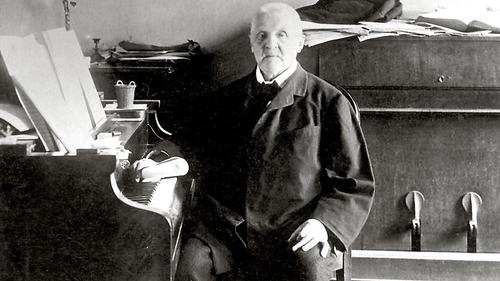

Anton Bruckner probably would not have relished his status as Hitler’s favorite composer.

As a devout Catholic, a humble and rustic man from the country, Bruckner engaged in none of the anti-Semitic polemics that make Wagner’s music, incomparable as it may be, a difficult proposition for many listeners.

So when the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra comes to Symphony Center Monday night to perform Bruckner’s epic Symphony No. 8, there won’t be a trace of the controversy that accompanied the orchestra’s attempts to perform Wagner.

“Wagner’s philosophy had absolutely nothing to do with Bruckner,” the orchestra’s music director, Zubin Mehta said, in a telephone interview from the Tel Aviv Hilton. “Bruckner hadn’t written a single word against Jews. Wagner’s book on the Jews was one of the most infamous books of the 19th century. I’m not defending the fact that we don’t play Wagner. I want to play Wagner. But you just can’t put Bruckner and Wagner together from that point of view.”

The Symphony No. 8, Bruckner’s last completed work in the form, is considered one of his greatest compositions. Conceived on a vast scale, with performances typically taking more than an hour and 20 minutes, the symphony has dark, organ-like sonorities, moments of shattering drama, a grave Adagio as long as an entire Mozart symphony and a blazing, thundering finale.

“He wrote it when he as absolutely at the height of his powers and at the height of his popularity,” said Paul Hawkshaw, professor of music at Yale University and author of the Bruckner section of The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. “People talk about Bruckner as being this spiritual composer, that his spirituality as a person comes out in his music, and I think in the Eighth Symphony this happens more than anywhere else.

“In the first movement, we have a man who is spiritually conflicted, and there’s a lot of tension there. But in the Adagio, it’s like a 20-minute hymn, and sometimes people who are not used to Bruckner get impatient because it’s so long, but if you give it time, by the time you get to the end, I believe you actually are taken to a different place. It’s so spiritually moving.”

Bruckner’s status as a Nazi idol came through no fault of his own, he said. As an unworldly man in late 19th-century Vienna, he got caught up in the musical and political controversies of the day, finding himself enlisted as a partisan of Wagner against the Brahms faction, never quite extricating himself, even after death. And Hitler, who was born just a mile or two from Bruckner’s birthplace, saw him as a fellow artist and victim of Jewish critics.

One of Joseph Goebbels’ best-known propaganda speeches came in the dedication of a bust of Bruckner at the Walhalla Memorial near Regensburg, an event that yielded a photo of Hitler contemplating the composer’s sculpted image. After Hitler committed suicide, the solemn music played on the radio was the Adagio from Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7.

“Bruckner himself had no interest whatsoever in either the German agenda or the Nazi agenda, and in fact was a staunch Roman Catholic,” Hawkshaw said. “But he was extremely naive, and he got caught up in this when he was alive and it just continued right through, really until the end of the Second World War. He was very much a part of the propaganda. I remember into the 1970s some of the faculty members here at Yale who had fought in the American Army in the Second World War refused to listen to Bruckner. They just wouldn’t touch it.”

Few conductors know better than Mehta the difficult of attempting to bring a Nazi favorite to Israel. Convinced that a composer as great as Wagner should not be excluded from a major orchestra’s repertoire, he announced plans in 1981 for the Israel Symphony to perform selections from Tristan und Isolde as an encore. As Wagner’s sensual harmonies floated through the hall, cries of “Hitler!” and “Nazi!” competed with shouts of approval, in a performance that ended with a standing ovation from most of the audience, according to an account by the Associated Press. He dropped subsequent plans to try again, after receiving word that tickets had been bought in blocks by people intending to disrupt the concerts.

But nothing like that happened with Bruckner. The orchestra has played him often in Israel, and the scale, grandeur and late Romantic tone of Bruckner’s music plays to the ensemble’s strengths, Mehta said. “We are very attuned to his style,” he said. “Bruckner’s Eighth is a colossus. It just fits well into the orchestral spectrum of this orchestra. The musicians are extremely at home playing this style. We play a lot of Richard Strauss also. And of course, a lot of Mahler.”

The Israel Philharmonic was founded in 1936 as the Palestine Philharmonic by the great Polish-Jewish violinist Bronislaw Huberman, who helped bring in hundreds of Jewish musicians fleeing Europe. For most of its history, however, the orchestra has played under Mehta’s baton. He first led the orchestra in 1961 as a guest conductor, became music director in 1969 and saw his title elevated in 1981 to music director for life. During that time, he presided over significant changes in the orchestra’s ethnic and musical composition.

“When I first took over the orchestra, almost half the orchestra were from the Austro-Hungarian empire,” he said. “Then came the influx of the ex-Soviet Union musicians who immigrated here. So today we have a mixture of ex-Soviet Union and those born in Israel, and we have a few Americans too. The Russians brought in their incredible virtuosity in string playing, which of course was a great advantage to the orchestral playing standard. And of course, one by one, we converted them to our Central European repertoire.”

Asked to name highlights of his time with the orchestra, Mehta thinks first of performances abroad, where the orchestra served as an ambassador for Israel, in events fraught with cultural and historical significance.

“There was the first time the orchestra appeared in Germany,” he said. “It was very important. We opened the Berlin Festival in 1971 with Daniel Barenboim as soloist and Fischer-Dieskau. It was a very moving experience. We decided to play the Israeli anthem instead of an encore. The audience didn’t quite know what we were playing in the beginning so they didn’t stand up. And then it became quite clear, and there were wet eyes in the audience.”

He took the orchestra across the border to Lebanon at the time of the 1982 war, where they performed under a tent for mixed Arab and Israeli audience. “And of course taking the orchestra to my country after years of diplomatic distance,” he said. “India had cut off diplomatic relations with Israel after the Six Day War. And in 1992, they resumed relations again, and in 1994 we went to India where the orchestra played free of charge with Itzhak Perlman and other Israeli soloists who donated their services for this great occasion and also from their friendship for me, to come to my country, which is something I don’t forget.”

Perhaps as a relic of Israel’s early socialism, the orchestra runs itself as a cooperative. There is no board of directors. The orchestra elects administrators and its music director. Although Mehta selects repertoire (along with an elected orchestra representative) and leads performances, he knows that when he stands on the podium, he’s ultimately standing before his bosses. How long will he stay?

“That depends on my colleagues,” he said. “I’ve always told them, I’m ready to pack my bags any time they want to make a change.”

Zubin Mehta and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra perform Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 at 8 p.m. Monday at Symphony Center. cso.org; 312-294-3000

Posted in Articles