DiDonato and Polenzani rule in Lyric Opera’s sleek, stylish “Tito”

The Lyric Opera of Chicago has only mounted La Clemenza di Tito once previously, a quarter-century ago, and it’s not hard to understand why. Mozart’s penultimate opera is a famously difficult work to pull off, with intermittent yet undeniably glorious musical moments hobbled by implausible characters and an often preposterous libretto.

For its final production of the season, Lyric Opera delved into Mozart’s Roman archive once again. Wednesday night’s opening performance of La Clemenza di Tito delivered a successful and largely vocally distinguished account of Mozart’s problematic opera seria, with terrific singing by its two stars, several superb young artists in the supporting cast and a sleek and visually striking production.

“The Clemency of Titus” tells of the title Roman emperor who is revered by all for his virtue and compassion. Those qualities are sorely tested by the perfidy of the spiteful Vitellia, who is in love with the emperor. Vitellia convinces her own besotted admirer, Sesto, Tito’s closest friend, to murder the emperor in revenge for his lack of attention. Further romantic complications arise when Tito selects Servilia as his bride, Sesto’s sister and the intended of his friend, Annio.

With its bewildering romantic entanglements, gender-bending leads (Sesto and Annio are both sung by mezzo-sopranos) and often ludicrous plot reverses—the fast-revolving door of Tito’s chosen empresses elicited laughter opening night—the opera would likely be shelved today, were it not for Mozart’s music. As with all late Mozart, there is a spareness and luminous beauty to Tito, which fits well with the Apollonian milieu, the music rising to an expressive nobility that reflects the emperor’s humanity and ultimate act of selfless forgiveness.

David McVicar’s stylish scenic design, retooled from his Festival d’Aix-en-Provence staging, is traditional yet highly effective, with a steep stairway stage right and Roman porticos with walls that slide in and out. Jenny Tiramani’s costumes offer white regalia for the pure-hearted Tito, elegant flowing gowns for the women, and period-traversing cool for the men including futuristic black armor for Publio and the Praetorian guard. Most importantly, the production is respectful of the character’s mutable extreme emotions and motivations, even at ludicrous moments that would motivate lesser hands to indulge in satire.

It’s a testament to Joyce DiDonato’s artistry that she can make such a weak, vacillating character as Sesto so riveting and compelling. The American mezzo commanded the stage Wednesday night whenever she appeared, bringing a charismatic presence and dramatic honesty to the indecisive Sesto. DiDonato’s rich, flexible voice was balm for the ears, and the mezzo threw off some dazzling coloratura at lightning tempos. One can go a long time without hearing “Parto, parto” sung with such poised feeling and commitment, and Sesto’s contrite aria in Act 2 was likewise suffused with deep sadness and glowing tone.

The rest of the cast was made up entirely of Ryan Opera Center singers, one current member and four alums. It is a testament to the success of the program that it can fill an entire cast with such gifted artists.

There are not many great tenor roles in Mozart operas, so one was thankful for the opportunity to hear Matthew Polenzani as the compassionate, besieged emperor. What a pleasure to hear Mozart sung with the power and refinement Polenzani brought to Tito’s music.

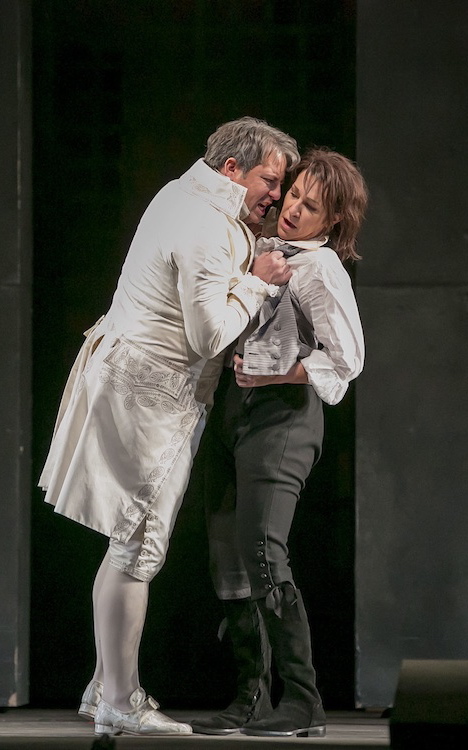

Dramatically, Polenzani was sensational, going beyond the plaster saint to create a rounded and conflicted human emperor—angry at the betrayal of those he trusted and conscious of his duty yet also wanting to forgive his enemies. Polenzani’s explosive rage at Sesto’s betrayal—with a hint of a homoerotic relationship going beyond mere friendship—brought a jarring intensity to their Act 2 confrontation, the tenor shaking DiDonato so violently, one feared he would loosen a filling.

While this production is a tribute to the Ryan Center’s successful mission of grooming young artists, it also, inadvertently, points out the occasional problems that arise with Lyric Opera’s over-reliance on Ryan Center alumnae, to the extent of sometimes placing singers in roles to which they are either not ready or unsuited.

Such was the case with Amanda Majeski as Vitellia. The soprano has enjoyed success at the Lyric, most recently as Eva in last season’s Meistersinger. But as the villainess who convinces the lovelorn Sesto to assassinate the emperor, Majeski was completely miscast, ill-suited vocally and out of her depth dramatically.

Granted, Vitellia is a tough role to pull off even for seasoned pros, and her angry rages and selfish egomania can often seem more comic than dramatic. Such was the case Wednesday night. Unlike her costars, Majeski failed to carve out a convincing characterization, her acting limited to mustache-twirling gestures (if she had a mustache) and arm-waving histrionics rather than coming from within.

Vocally Majeski seemed equally uncomfortable, her Mozart style centered on isolated loud notes and chesty contralto tones, without much going on between the extremes. Vitellia’s unhinged personality is deftly painted by Mozart in her fitful bursts of frantic coloratura, but Majeski passed on much of the fireworks, simplifying the passages or tiptoe-ing through them so warily that they barely made an impact.

The rest of the cast was first rate. It was wonderful to see DiDonato and Cecelia Hall together at the start of Act 2: two mezzos in trouser roles, one securely established as one of the leading artists of our day and another who seems on the brink of stardom. Hall was sterling as the selfless Annio, singing with a creamy rich tone and showing dramatic acuity throughout. Emily Birsan, a current Ryan Opera Center member, sang with apt youthful purity as Servilia, Annio’s beloved, blending smoothly with Hall’s lovely mezzo.

The excellent bass-baritone Christian Van Horn etched another superb character portrait as Publio, captain of the Praetorian Guard, singing with sonorous depth and surprising agility for such a big voice.

Taking over stage duties from McVicar, revival director Marie Lambert moved the action naturally yet skillfully, avoiding stiff tableaux in a work that can fall prey to didactic visuals. Only McVicar’s final twist at the curtain seemed misjudged, coming out of left field.

In addition to taking on the non-speaking role of the coconspirator Lentulo, movement director David Greeves devised effective ninja-style exercises with long knives for the black-armored Praetorian guard.

After a rather poky overture, Sir Andrew Davis conducted with his usual Mozartian grace, bringing out the lyrical warmth and nobility of this score. Michael Black’s chorus sang with customary fervor and corporate refinement.

La Clemenza di Tito runs through March 23. lyricopera.org; 312-332-2244.

Posted in Uncategorized

Posted May 12, 2017 at 2:29 am by Paul

I always take exception to the term ‘late Mozart’ with it’s implication of the composer’s mortal foreknowledge. In 1791, Mozart’s fortunes were decidedly on the upswing. In addition to the large Imperial commission for Tito, Die Zauberflote was a big hit, Haydn had premiered Figaro and Don Giovanni in London to great acclaim, and the London audience was hungry for more. Then he got some bug (typhoid? strep?), which didn’t distinguish between rich and poor. He probably had as much knowledge of pending doom as any of Mary Mallon’s employers. Perhaps the most tragic aspect of Mozart’s death was its irony