CSO festival delivers jarring Shostakovich and powerful Prokofiev

The three week “Truth to Power” festival by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and conductor Jaap van Zweden continued Saturday with one work by each of the three featured composers, all produced within a six-year span.

The festival theme is more marketing gimmick than an accurate reflection of a common stylistic or political thread, yet the narrow focus on three mid-century giants certainly has merit. While each has a genuinely personal voice, Britten, Shostakovich, and Prokofiev relied mostly on received traditions of western classical music, while the heavy lifting of the musical innovation (an important measure of the risk-taking implied by the pithy designation) that was happening elsewhere.

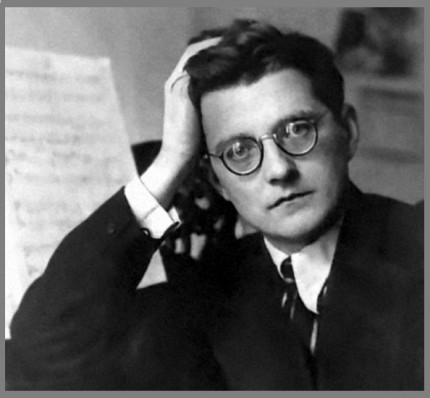

Shostakovich’s wonderfully weird Five Fragments from 1938 are about as close to the cutting edge as anything in his oeuvre, and, not surprisingly, were hidden from audiences and authorities until a belated premiere in 1965. Given the lavish attention paid to his music in recent years, it was surprising to learn that this performance at Symphony Center was a CSO debut. Conceived in a single day as the composer was wrestling with his Fourth Symphony, these miniatures give a tantalizing hint at the paths Shostakovich may have taken had he not been under the heavy thumb of his Soviet antagonists.

Even with the works’ relative brevity, the otherwise engaged audience seemed restless and puzzled by these orchestral sketches, in part because most of the Shostakovich trademark peculiarities were absent. Thickly textured bombast was replaced with a lean, almost gaunt use of orchestral color. Instead of the mind-numbing melodic repetition that is a feature (for better or worse) of many of his symphonies and string quartets, ideas vanished almost as soon as they appeared. And for a composer generally tethered to the tonal norms that others of his generation were happily shredding, key centers were often vague. Composers as disparate as Webern and the neoclassical Stravinsky seem to lurk in the distant background.

The opening movement sounded more like a woodwind quintet than a symphonic creation, with restless and meandering lines sliced off by a final rude clarinet interjection in the final bar. The second movement is also thinly scored, adding only a few brass solos and an amusingly grumpy double bass section, while the eerie and nearly atonal third movement finds the violins sustaining ghostly lines near the end of their fingerboards. If you can imagine a scrap of a Mahler scherzo stripped of all parts except a solo violin, double bass, and snare drum, you’ll have a good idea of the impression left by the endearingly scrawny final sketch. Associate concertmaster Stefanie Jeong and principal bassist Alex Hanna had great fun in their respective roles, and van Zweden brought cohesion to a score that could have easily seemed aimless and splintered.

While the slogan “Truth to Power” has been co-opted by any number of political causes, it was original coined in 1955 by the Quakers as a plea for peaceful resolutions to world conflict. Britten’s well-documented pacifist leanings were taking shape in 1940 as his Sinfonia da requiem was commissioned by the British Council for “the reigning dynasty of a foreign power,” later revealed to be the Japanese Imperial dynasty. While explicitly dedicated to the memory of his recently deceased parents, it was easy to hear broader intentions in van Zweden’s dark, brooding account of the Lacrymosa. The portentous skittering of the Dies Irae featured deft solo passages by trumpeter Chris Martin and grim incantations by the trombone section.

The CSO is rightly regarded as a leading exponent of Mahler and Strauss, but their strengths are equally suited to the vivid colors and high-flying virtuosity of Prokofiev’s music. After some mildly unsettled ensemble work in the opening minutes, van Zweden corralled his forces for a vigorous and idiomatic reading of the Symphony No. 5.

Tempos seemed right on the mark and, with rare exceptions, balances were carefully calibrated to allow brilliant solo passages to poke through the hyperkinetic orchestral fabric. This is one of the few works in the symphonic canon to extensively feature the diminutive E flat clarinet, and Sue Warner’s playing was a perfect delight. Flutist Mathieu Dufour and oboist Eugene Izotov were exceptionally unified in their duo passages, and the violins soared gloriously in the intoxicating third movement. Some conductors push the tempo in the finale harder than van Zweden, but his judicious pace allowed every delectable detail to reach the ear.

The program will be repeated 7:30 p.m Tuesday. cso.org; 312-294-3000.

Posted in Performances