At 25, Chicago Philharmonic is looking to a bright and adventurous future under Scott Speck

Some call it the best kept secret in Chicago.

Many of the two hundred musicians that make up the Chicago Philharmonic play together in ensembles of a different name, like the Lyric Opera Orchestra and Ravinia Festival Orchestra. But for twenty-five years the Chicago Philharmonic has been serving the city with enriching programs of its own. And now the orchestra, in its silver anniversary year, has a renewed mission to grow and blaze its own path.

“Our vision is not to be another or a junior Chicago Symphony,” said Scott Speck, conductor and artistic director of the orchestra. “Our vision is to carve out a separate identity as an orchestra that is extraordinarily flexible in terms of the numbers that are needed [and] the events that it plays for.”

On the surface the Chicago Philharmonic operates just as many performing arts organizations do, with the ensemble supporting its season through ticket sales, individual donors, and funds from grants and foundations. But the Philharmonic also raises a portion of its cash through contracted performances. The ensemble serves as the main orchestra of the Joffrey Ballet and also plays a number of concerts with the Ravinia Festival.

Following the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, the Chicago Philharmonic took a long hard look at its organizational structure. Their annual budget for that season stood at about $400,000 and the orchestra was running a small budget deficit. The orchestra saved money by down-sizing its final two programs of that season into chamber music concerts. The cost-saving measure worked in the short term, with the Philharmonic running a surplus of $36,000 in 2009. Their finances dipped again the following year to a deficit of $13,000.

Yet due to the improving economy and stronger leadership within the organization over the past four years, the Chicago Philharmonic has run a budget surplus of between $5,000 and $40,000, and they currently operate with an annual budget of $1.6 million, according to figures given by Donna Milanovich, executive director of the Chicago Philharmonic Society.

A contributing factor to the ensemble’s rosier financial picture took place in 2012, when the Philharmonic reorganized into a musician-led entity, a model that is unusual among U.S. orchestras.

“You see all over this country work stoppages and so many musicians being locked out and various other things going on that stopped the music, either temporarily or permanently, in different cities,” said Speck. “I think a new model is called for, So in this new model there are no adversaries because everyone, throughout the management, throughout the rank and file, the orchestra has the musicians’ best interest at heart.”

“It was the musicians of the orchestra that helped to rally it and get us through that sort of difficult economic time,” added Milanovich. “And the result was that there was more [and continued] involvement from the musicians.” Furthermore, she said, “It was partly a natural evolution. We already had loosely that structural ideal, and I think that it just helped us formalize what we do.”

More than half of the Chicago Philharmonic’s board is now made up of its musician members, and the majority of its committees operate under musician leadership. Speck himself emphasizes the “we” instead of the “I” when it comes to the orchestra’s programming because, he noted, the process is so collaborative.

Since being named artistic director last year Speck, 52, has left an indelible mark.

Born in Boston and educated at Yale and the University of Southern California, Speck has developed a reputation as a conductor with an intimate insight into the orchestral repertoire and a knack for pulling a chamber music intimacy from ensembles under his baton. He counts some of the world’s leading conductors among those who have had lasting effects on his career.

“I feel like one of my biggest influences as a conductor is Claudio Abbado, who I have not worked with but have experienced many many times as a conductor,” said Speck. “He had this amazingly collaborative style with the orchestra that has had the biggest influence on my rehearsal techniques and relationships with the human aspects, the musicians themselves, more than anyone else.”

Between college and graduate school, Speck studied in West Berlin on a Fulbright Scholarship. There, he sang in nearly sixty performances with the Berlin Philharmonic Chorus under a range of conductors, which included Abbado, along with Erich Leinsdorf, Riccardo Chailly, Antal Doráti, and Seiji Ozawa. “The way that the Berlin Philharmonic and many of the greatest European orchestras communicate onstage is such a beautiful thing to watch,” he said of the experience. “They breathe and allow themselves to physically respond to the music in such a way that it can be read across the stage by their colleagues and they create an incredibly unified sound. That inspired me and has inspired me my whole career.”

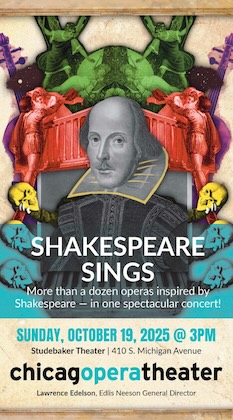

One way that Speck is helping the Chicago Philharmonic carve out its own niche is through innovative, multi-dimensional, and interactive programming. Their performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring last season featured a modern dance troupe from Portland, Oregon in a staged production of the ballet. The Chicago Philharmonic also worked with members of the city’s Court Theatre and Chicago Shakespeare Theatre, who acted out scenes to accompany music from Richard Strauss’s adaptation of Le bourgeois gentilhomme and Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet suite.

The five masterworks programs of the orchestra’s current season represent the five senses, with each concert offering extra-musical enhancements. The concert about smell will give the audience a chance to sample different types of perfume. The one about taste will offer concertgoers food and drink.

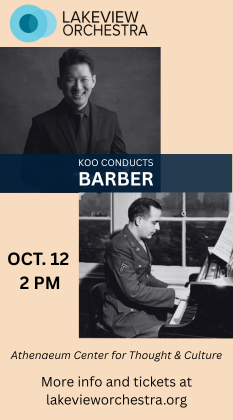

Moreover, this year’s Philharmonic season features some adventurous programming choices, such as Samuel Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915 (November 16), works by Martinů and Milhaud (February 15), De Falla’s Nights in the Garden of Spain (April 19), and Kenji Bunch’s First Symphony and Jennifer Higdon’s blue cathedral (June 7).

“I think that living in a city that has so many riches as far as musical offerings go, it is important for us to not just play again what have been played umpteen times,” Speck said. “However, I think that looking for something new and different to play is only a side effect or an offshoot of our programming philosophy [which is] to create something that is really relevant and really interesting.”

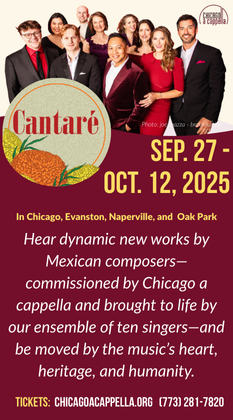

The Chicago Philharmonic’s first concert of the season, which takes place next Sunday at Evanston’s Pick-Staiger Hall, features two little-heard Danish works, Carl Nielsen’s seminal First Symphony and Niels Gade’s stirring Violin Concerto.

“Carl Nielsen is such a unique voice and it was in the First Symphony where I think that voice really was first heard,” said Speck. And the Gade, he added, needs a good violinist, a task more daunting than one might think. “It’s not so easy because so few violinists have even played it, let alone played it well. But we scoured, literally, the world and we found someone who, we think, plays it the best.”

That musician is Danish violinist Christina Åstrand, who will be making her U.S. debut with the work. Åstrand has recently released a critically acclaimed recording of the concerto, which has done much to familiarize American and European audiences with Gade’s music.

Yet “even in Denmark, it’s not played at all,” Åstrand said of the concerto. “I think it’s a shame because it’s lovely, so lovely.”

“It’s music from the Golden Age in Denmark,” she added. “On the surface it sounds pretty, but there’s so much drama in these lovely melodies. This hidden passion, sizzling underneath the surface, catches my attention every time.”

But innovative and wide-reaching programs are just a part of what makes the Chicago Philharmonic unique, Speck noted. “What makes the organization so special is that it’s not just about one person’s vision. It’s about the collective vision of this remarkable group of musicians.”

Scott Speck will open the Chicago Philharmonic’s 25th anniversary season 7:30 p.m. Sunday at Pick-Staiger Hall, Evanston. The program includes Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet Overture, Arvo Pärt’s Wenn Bach Bienen gezüchtet hätte (If Bach Had Been a Beekeeper) Nielsen’s Symphony No. 1 and Niels Gade’s Violin Concerto with soloist Christina Åstrand. chicagophilharmonic.org

Posted in Uncategorized