Fiery Nielsen sparks Nordic opener from Chicago Philharmonic

One could put together a notably adventurous season just by combining the repertory of Chicago’s top suburban orchestras. The fact that most offer consistently excellent playing as well as thought-provoking programs makes musical excursions outside the city even more essential.

The Chicago Philharmonic opened its 25th anniversary season Sunday night with a “Nordic” program of intriguing yet accessible rarities that could serve as a model of its kind. In its second season under Scott Speck, the orchestra was in characteristic top form with boldly projected and largely polished performances at Pick-Staiger Hall, even if the evening overall proved something of a mixed bag.

With partial sponsorship from the Danish embassy, the main works of the evening offered music from the country’s two leading composers, Carl Nielsen and Niels Gade.

As Speck noted in his informed and informal verbal notes, Nielsen’s distinctive voice was largely formed even in his earliest works. The Symphony No. 1, written at age 27, showcases Nielsen’s style—the edgy, bustling energy, noodling, rhapsodic wind lines, and vaulting key changes, the First Symphony moving from G minor to C major over its four movements.

Nielsen’s first of six works in the genre is a score brimming with confidence, and Speck and the Philharmonic musicians served up a lively and idiomatic performance, the outer movements imbued with ample vitality and swagger. The Andante is one of Nielsen’s first great slow movements and, one jarring horn lapse apart, the conductor drew playing of great warmth, polish and ardor.

The third movement is especially characteristic and Speck brought out the folkish charm of the wind writing while letting the brass statements sound a more somber note. The performance was rounded off with a crackling finale that ratcheted up the excitement until the final resounding blast of C-major.

Speck clearly has great sympathy for Nielsen’s tricky idiom. Let’s hope that this fine performance heralds the start of a complete Nielsen symphony cycle from Speck and the Philharmonic.

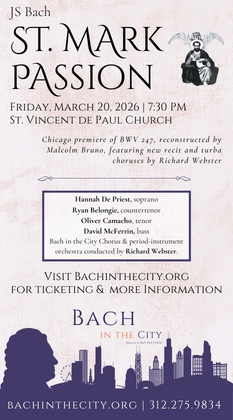

The Nielsen was preceded by a brief work from Arvo Pärt, Wenn Bach Bienen gezuchtet hatte (If Bach Had Been a Beekeeper). The Estonian mystic is not noted for his sense of humor yet this quirky, inscrutably subversive work shows some understated wit in its buzzing string lines, which blend with minimalist repeated piano and percussion chords until a resolution in a glowing cadence. One has the feeling that the work would be more effective in its original version for smaller forces yet Speck led a worthy, well blended rendering.

Niels Gade’s reputation has slumped considerably since his late 19th-century heyday. The criticism of the Danish composer as a kind of Mendelssohn without the tunes isn’t far off, but his attractive music surely deserves more outings than it gets these days. Kudos to Speck for programming Gade’s Violin Concerto, which, notwithstanding the naysayers, has a rich vein of engaging melody and ample display opportunities for the soloist.

Christina Åstrand has won plaudits for her recording of her countryman Gade’s concerto, yet the Danish violinist’s performance overall proved more competent than inspiring.

The opening Allegro con fuoco was taken at a decidedly cautious tempo—barely an Allegro and little fuoco to be heard—the soloist’s heavy bow arm and lack of virtuosic fizz keeping the performance earthbound. The finale—a moto perpetuo that seems inspired by Mendelssohn’s concerto for the same instrument—was taken in a similarly dextrous fashion until Åstrand’s final burst, which showed some of the bravura fireworks lacking previously. Speck’s choppy accompaniment was too often cut from the same cloth, with wind playing overloud and little expressive nuance or sculpting of the lyrical pages.

It’s been a good week for rarely heard Shakespeare-inspired Tchaikovsky tone poems with the Chicago Symphony performing The Tempest Friday night and the Philharmonic offering the Hamlet Overture on Sunday.

With such an ambitious program something was bound to suffer from lack of rehearsal time and this appeared to be it. Speck clearly conveyed the power and drama of Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet, but it was hard to avoid the feeling that the Philharmonic’s music director has not yet gotten a handle on Pick-Staiger’s very live acoustic. Everything sounded far too loud with Ophelia’s wind theme coarsely literal and lacking in delicacy, and tuttis aggressive to the point of being painful with ear-splitting percussion.

The Chicago Philharmonic’s next program is 3 p.m. November 16 at Nichols Hall in Evanston. Joel Smirnoff conducts the orchestra in Rossini’s Overture to La scala di seta, Haydn’s Symphony No. 103, and Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915 and arias from Don Giovanni with soprano Asako Tamura. chicagophilharmonic.org

Posted in Uncategorized