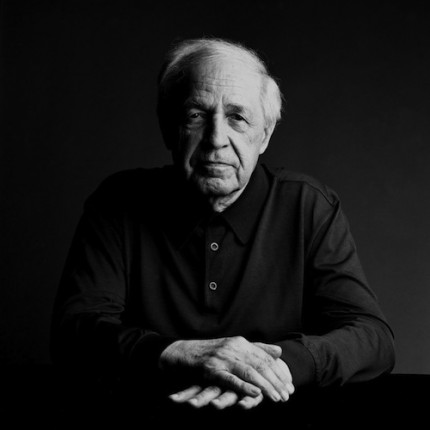

Pierre Boulez 1925-2016

Pierre Boulez, one of the most important figures in 20th century classical music, is dead. His death Tuesday evening was announced on the website of the Philharmonie de Paris, part of the Cité de la Musique complex in Paris.

The Cité is a concrete manifestation of Boulez’ significance to both French and international musical culture. Boulez was a composer and conductor of stature: among other positions, he was music director of the New York Philharmonic from 1971 to 1977, and with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra was a regular conductor from 1991, before being appointed principal guest conductor in 1995. He passes as the CSO’s Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus and an Honorary Member of the Philharmonic-Symphony Society.

In New York, he attempted innovations that in many ways have become commonplace to the way orchestras approach their audiences: new music series, chamber concerts, and informal events both in what is now David Geffen Hall and away from the Philharmonic’s Lincoln Center home. While his influence on subsequent music-making can be hard to discern—his style as a composer was unique to himself, and he was not a pedagogue as a conductor—he leaves behind an essential legacy of building institutions, like the Cité and most prominently the Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique (Ircam). In this role, he had no peer in the history of classical music.

Boulez (born March 26, 1925, in Montbrison, France), began his career as a serious musician during World War II, in German-occupied France, where he studied with Messiaen at the Paris Conservatory. The elder composer introduced him to both both contemporary and non-Western music.

Boulez’s compositional output is both fascinating and uneven. He was a leader of the school of serial, atonal composition that, through the academies, dominated classical music in the mid–20th century. His Sonata pour piano no. 2 is a muscular exemplar of that style, but his Le Marteau sans maître drove the musical concept into an objective, lifeless dead end.

Boulez had a brilliant intellect and could be an intimidating didact. In an ideological era, he battled with ideas as much as music. A budding friendship with John Cage was demolished by differences in aesthetic values: while Cage’s Music of Changes can sound like a companion to Boulez’ Sonata No. 2, Boulez could not reconcile Cage’s different compositional process with his own.

But Boulez was ultimately too agile to be caught in a stylistic trap. While never completely abandoning atonality, he expanded his harmonic palette and became increasingly interested in exploring instrumental color, at times with electronic enhancement. Pieces like Pli selon pli, a setting of Mallarmé poems; Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna; and “…explosive-fixe…”, are not only involving and satisfying works in their own right, but establish a vital reconciliation of serial music with Debussy’s legacy of organic, tonal forms. They are high points in a compositional output that Boulez frequently revisited and revised. He left the impression that he was always looking for something better to say, or a better way to say what he thought, and the 2013 collection of his complete works has on the back the indication: “work in progress.”

Boulez was a controversial conductor whose performances and recordings with the Philharmonic, the CSO, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic, and many more ensembles, divided his own fans and those of the composers he explored. Focusing on the structure and orchestral detail of the scores, his views on Stravinsky and Debussy are, if not every listener’s first choice, essential to understanding the work of those composers. And his recordings of Bartók, Ravel, Ligeti, Berg, Webern, Schoenberg, and Messiaen are among the finest available.

In the traditional repertoire, Boulez’s detailed approach yielded inconsistent results. He found his way to Mahler through Berg and Schoenberg, and his interpretations of the vocal symphonies are fresh and fulfilling. With the others, revelatory passages and movements run up against a lack of vision of the overall form. Boulez was an unexpected choice to conduct the performances of Patrice Chereau’s Ring at Beyreuth, but the results turned out to be historic and enduring.

In New York, the Philharmonic concerts of Wagner, Strauss and Sibelius that will be heard January 7–9, and January 12, will be dedicated to Boulez. In a statement from the orchestra, music director Alan Gilbert said: “Pierre Boulez was a towering and influential musical figure whose Philharmonic leadership implicitly laid down a challenge of innovation and invention that continues to inspire us to this day. To me, personally, he also was an unfailingly gracious mentor and friend. I will miss his musicianship, kindness, and wisdom.”

Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director Riccardo Muti said, “With the loss of Pierre Boulez, the world of music today is infinitely poorer. As both an admirer and friend of the Maestro, I am deeply grateful for his contributions, as composer, conductor and educator, to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, with which he had a collaboration of nearly 50 years, and served so brilliantly as its principal guest conductor and conductor emeritus. His great musical artistry and exceptional intelligence will be missed.”

Posted in Uncategorized

Posted Jan 06, 2016 at 10:32 pm by Odradek

RIP to a great musician and musical thinker – a real force in modern music. I count myself lucky to have heard him with the CSO back in the 90s.

Posted Jan 07, 2016 at 12:42 pm by Roland Buck

Boulez was a major figure in the movement in classical music that led it into the blind alley of atonality, serialism, harsh dissonism, and cold, soulless abstractionism. For want of a better term, I will call this type of music “Twentieth Century Modernism.” They succeeded in turning much of the second half of the twentieth century into a dark age of classical music.

By the end of World War Two, Twentieth Century Modernists succeeded in entrenching themselves as a hegemony that imposed its views of how new music should be composed so effectively that it became very difficult for composers who wanted to compose beautiful, consonant, and tonal in the broad sense music to be heard and have their music performed. Boulez actively worked to supress the music of such dissidents. This hegemony was every bit as effective in imposing its views of what new classical music should be like as Stalin was in imposing his views in the Soviet Union. As a result, the new music that got to be heard and performed, was ugly, unpleasant, and incredibly boring, and the majority of the concert audiences rightfully hated it, and still does.

Fortunately the twentieth century is over and Twentieth Century Modernism has become old hat and is on the way out. Younger composers are, once again, composing music that is consonant, tonal in the broad sense, and contains beautiful and powerful melodies. While classical music is still struggling to overcome the tremendous harm that was done to it during the dark ages, it will be very different and much better in this century than what passed for new music in the dark ages.