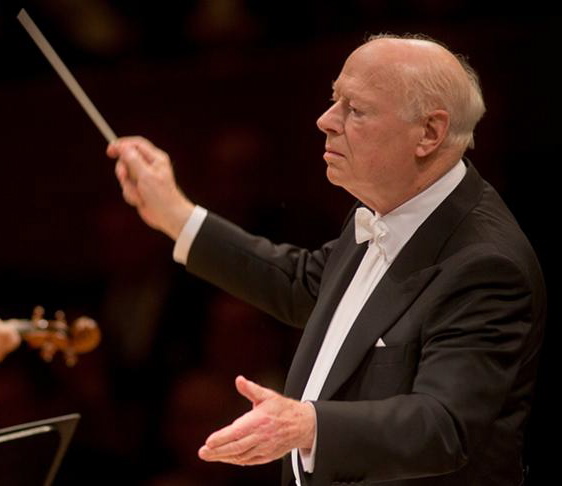

Haitink, CSO reach the summit in Strauss’s “Alpine Symphony”

Richard Strauss’s tone poems are celebrated for their quirky and distinctive scenarios, melodic warmth and outsized orchestration. But the composer outdid himself in his penultimate work in the genre, An Alpine Symphony, which was the main event of Thursday night’s Chicago Symphony Orchestra concert led by Bernard Haitink.

Premiered in 1915, the vast 50-minute work depicts a rigorous mountain climb–past waterfalls, mountain pastures and thickets to the summit, the downward climb and a violent thunderstorm en route.

Befitting the subject, Alpine Symphony is scored for a massive orchestra even by Strauss standards; celesta, organ, heckelphone, triple and quadruple woodwinds, thunder and wind machines, and 20 horns–12 offstage and four doubling on Wagner tubas.

Yet apart from the brassy spectacle and picturesque effects (cowbells, organ, etc.), there are substantial musical riches and an underlying philosophical depth in this vast work. An early sketch contains a note for the final section, “Liberation through work.” One need not strain too much to see Alpine Symphony as a Strauss metaphor for life, work and career—striving against odds, and overcoming obstacles, storms and challenges along the way to achieve great things and taking a sense of satisfied accomplishment at the end of the arduous journey.

Befitting his Straussian bona fides and rigorous textual integrity, Haitink was a consummately skillful conductor/sherpa, keeping forward momentum on the climb and drawing beautifully polished and committed playing. Characteristically, he tamped down the sonic spectacle, not always to the music’s advantage. The huge brassy climaxes of the opening sunrise and the summit sequence made gleaming impact but felt a bit reined in Thursday. Haitink’s interpretive style of extreme moderation was clear in the meticulous balancing and good taste—but do we really want good taste in Strauss’s Alpine Symphony?

Haitink’s unflashy approach paid off, however, in the extended final section (which completely eluded Daniel Barenboim in his 1992 CSO performances and recording). Here Haitink’s concentration and mastery of the long line maintained tension in the long, slow descent and return to night, ending the tone poem on a note of earned quiet contentment.

The CSO is on a roll after last week’s extraordinary Falstaff performances under Riccardo Muti, and–apart from a rather spindly oboe solo by Michael Henoch on the summit–the playing in Alpine Symphony was outstanding across all sections. Guest principal horn Richard Sebring (associate principal of the Boston Symphony Orchestra) was simply terrific in his playing of the tortuous solos, backed by the large horn contingent (onstage and off) with equal precision and sonic punch. Clarinetist Stephen Williamson brought an apt rustic mountain quality to his solos and, led by Christopher Martin, trumpet playing was bright and clarion throughout.

The evening began in lighter fashion with Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22 with Till Fellner as soloist.

The Austrian pianist delivered first-class Beethoven at his last CSO appearance four years ago and Fellner’s Mozart Thursday night was on the same high level.

K.482 is contemporaneous with Le nozze di Figaro and there is an operatic quality in the concerto, evident in the woodwind writing as much as the soloist role. Fellner provided supremely stylish and idiomatic Mozart playing, with fluent and elegant passagework and a pearly, crystalline tone. He brought refined yet searching introspection to the somber meditation of the Andante, and just the right intimate geniality to the skipping, children’s song-like main theme of the finale.

At tines one wanted a lighter touch from Haitink’s somewhat po-faced accompaniment but the conductor proved a close and simpatico collaborator. The woodwind playing was glorious, not least the aria-like duet between bassoonist Keith Buncke and guest flutist Lorna McGhee (Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra principal).

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday. cso.org; 312-294-3000.

Posted in Performances