Spektral Quartet preps for Feldman’s six-hour String Quartet No. 2

“This piece is so much about where you’re at personally–the music takes on different meanings based on the kind of day you’ve had, or your particular emotional state. The people who come to this concert will be so much a part of it.”

So predicts Doyle Armbrust, violist in the Spektral Quartet. The work Spektral will be playing Saturday night in its Chicago premiere at the Museum of Contemporary Art will be Morton Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2–an unusual, challenging, and deeply involving experience for musicians and audience.

The most obvious challenge in Feldman’s Second Quartet, and likely the reason it has taken more than 30 years for the first Chicago performance, is that the piece’s duration is six hours. (The sole complete recording, by the FLUX Quartet, lasts 6 hours and 7 minutes. Live performances have an uncanny way of clocking in consistently at around 5 hours and 45 minutes.) The musicians play continually, with only a slight pause to turn pages, and there are few moments that rise above the dynamic level of piano. The physical demands of a performance are inseparable from the mental ones, and stand alone at the extreme end of the classical repertory.

Preparation is unique: Spektral has been rehearsing the piece in sections, but the Saturday performance will be the first not only for Chicago but literally for the musicians. “We’ve been doing chunks, building those up in terms of duration before the show,” Armbrust says, “but we won’t play it through completely until the show itself.

“In a string quartet, your job is to prevent the unknown from happening. You rehearse so much to know exactly how the concert is going to go. This is the first time I can think of where we’ve done a piece where we won’t have played through the entire thing beforehand. It’s a very strange experience and kind of exciting, to be honest.”

For the challenge of sitting in a chair and playing straight for six hours, Spektral has enlisted the help of Alexander Technique expert Andrew McCann. This is especially important, as Armbrust points out, for the “violin and viola,” which demand “such an asymmetric way to hold your body. We’re actively shaking [our arms and shoulders] out as we play. It’s a pretty minor movement that may not register to the audience, but it’s a basic movement that helps us keep from getting stuck,” with a frozen shoulder.

Written in 1983, Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2 is not easy for audiences either, which makes the venue additionally important. Spektral is not playing in a traditional concert hall but a fourth floor gallery space, which will make it easy to the audience to shift their positions, take a bathroom break, even check out an exhibit or get a drink. Feldman himself didn’t expect anyone to sit still, or even stay awake, during a full performance; but if one is rested and comfortable, it can be surprising how easy it is to take it in from beginning to end.

The repertory of music with long duration is infinitesimal, even esoteric. Satie’s Vexations has a related form in that it uses extended repetitions of small bits of material, but the goal is continuation, duration. The English eccentric Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji wrote music of frequently punishing duration, such as the four-hour Opus Clavicembalisticum for solo pianist, but his music is high-romanticism blown up to gargantuan proportions. The running time for a performance of Götterdämerung can approach six hours, but that is an epic narrative, moving forward via separate scenes with extended intermission breaks.

Feldman’s ideas share nothing with the above but time, and his notion of that dimension is entirely different. When he composed long works like String Quartet No. 2 and For Philip Guston, he had left behind his early experiments with graphic notation, open forms and improvisation, and gone through a middle period where he experimented with combining unsynchronized instrumental lines in such pieces as Why Patterns? By the mid-1980s, Feldman was using plain, standard musical notation, with every note, rest and dynamic marking written out.

The music is not written to fill a long duration; instead, the music is made to go from the first bar to the last, and takes a long time to complete. That distinction is crucial: the String Quartet No. 2 is not an experimental or aleatoric work—designed to see what might happen—nor is it a particularly avant-garde piece, made in order to provoke some element of the Western classical tradition.

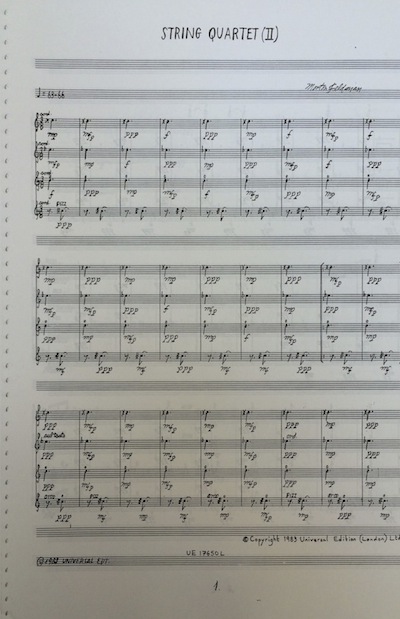

Beginning with a tempo marking of quarter note equal to 63–66 beats per minute, and a series of tone-clusters, the piece slowly builds a quasi-traditional large scale structure through the simplest and subtlest means.

Feldman wanted his music to be slow and quiet, but he did not want it to be boring or mindlessly repetitive. String Quartet No. 2 has an easily identifiable introductory section, a few important interludes and even a pause, with true silence, leading to a coda. The bulk of the work is made up of single bar phrases repeated several times even up to eleven. These include rapid little runs and, especially, an important phrase that sounds like it’s rocking back and forth, and through which we can hear clear harmonic motion. These phrases are musical bricks, each one laying out a bit of the work, the shape and experience which comes through in their accumulation.

In a sense, nothing could be more classical, although Feldman eschews the idea of development that dominated 19th-century music. Hearing the entire quartet as an enormously long sonata-allegro movement is not an unreasonable argument.

But the real form and point of the piece is time, and how time can be static, and how musical structure and expression can do something important that is different than moving the piece along to an anticipated harmonic and/or dramatic resolution. “There’s no narrative, it doesn’t tell you anything,” Armbrust points out, believing the listener “can mold it as you want.”

There are plenty of technical challenges: Feldman writes a phrase, then varies it with slight, but exact, changes in rhythm, and the musicians must play that clearly. The opening pages call for each instrument to play at a different dynamic, changing in almost every measure. There are extraordinarily complex rhythms, and clusters of harmonics that are a challenge to keep in tune.

Counting is difficult, not just maintaining the tempo (the group usually follows an eighth-note pulse), but in keeping the exact number of repetitions in order.

“The music tells us who the leader is,” Armbrust explains, but everyone has to be constantly alert. “It tends to be pretty clear, who [cues] these chains reactions.” Even so, “you just have to accept that someone’s going to miss that there were five repeats in that measure, instead of four. The leader [cues] the next group of repetitions, and it’s right, even if it’s not,” according to the score. This is some of exciting tension one can anticipate.

There are specific things to look forward to within the larger experience, passages of sturm und drang and calm serenity. Armbrust’s favorite part is what he calls the “storied page 22.” “Tonally it’s approachable and attractive, and it precedes the hardest chunk of the score. It’s a nice moment of rest,” he adds before diving into the complexities of the remaining hundred pages of the score.

As unlikely as one would think, there is something of a gentle groundswell slowly building for String Quartet No. 2. Along with their recording, FLUX Quartet has performed it half a dozen times, and the Calder Quartet played it at the Cloisters in New York City last November (violinist Tom Chiu of FLUX and the Calders have been generous with their advice to Spektral, says Armbrust).

As much as digital media is disparaged for destroying attention spans, so has it also made it possible to experience long-duration works, like the Second String Quartet, without having to flip the LP or change the CD. The pervasive reach of ambient music has also made it easy to create long periods of stillness.

Armbrust also sees interest in Feldman’s music on the rise in Chicago.

“There’s an attitude like, ‘Oh, yeah? I’m going to listen to Feldman 2 and read Infinite Jest!’”

Spektral Quartet plays Morton Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2, 6 p.m. Saturday at the Museum of Contemporary Art. experience.mcachicago.org

Posted in Articles