Gaffigan leads the CSO in a pair of American classics

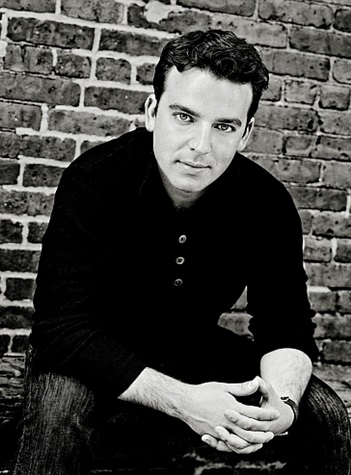

Having returned from its West Coast tour, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra was back on the job Thursday night at Symphony Center, in a program conducted by James Gaffigan.

In the first seven seasons of Riccardo Muti’s CSO tenure, American music has largely been confined to a handful of premieres by composers in residence, with an especially glaring neglect of homegrown works of the 20th century.

Happily, the current season shows a marked improvement on that front with several American composers on tap, including two works by Leonard Bernstein and Samuel Barber heard Thursday night. The program will be repeated Saturday night in Urbana but too bad that it was only being presented twice in Chicago. It’s also too bad that all of the woodwind principals are taking the week off.

Like many orchestras across the country, the CSO is marking the 100th birthday anniversary of Leonard Bernstein this season. Three of the celebrated composer-conductor’s works will be performed in Chicago, including the Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront, which opened the evening.

Elia Kazan’s taut, gritty film depicting union corruption on the New Jersey docks holds up extraordinarily well with a staggering performances by Marlon Brando and an equally inspired supporting cast (Rod Steiger, Eva Marie Saint, Lee J. Cobb and Karl Malden). Bernstein’s score for the 1954 film strikingly evokes the lurking violence and danger of the film’s urban milieu, mixing a fragile lyricism and pounding, jazz-inflected pulse.

The composer, however, fumed over cuts made to his music in the finished film–so much so that Bernstein never wrote for the movies again. He did, however, compose his Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront, drawing on music used in the film as well as passages that wound up on the cutting-room floor.

The result is–along with the near-contemporaneous West Side Story–one of Bernstein’s most successful compositions and, arguably, his finest concert-hall work. Scored with brilliance and audacity for large orchestra–including double timpani and saxophone—the Suite shows Bernstein’s easy assimilation of American vernacular–in this case, jazz–with classical form in a work that avoids the sentimentality and pretentiousness of his later works.

Some transition points could have been handled more adroitly, but for the most part Gaffigan led a full-blooded, idiomatic performance that put across this driving, aggressive music. The performance also conveyed the score’s sense of urban loneliness, most effectively with Daniel Gingrich’s evocative horn solos, onstage and off. Not so much the pedestrian rendering of the beguiling flute theme by the assistant principal, though Gaffigan led a soaring reprise in ardent fashion without going over the top. The strident, grinding brass chords of the coda struck the right ambivalent note.

Over the past two decades Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto has gradually worked its way into the standard repertoire, and rightfully so as one of the most beautiful and well-crafted works in the genre.

James Ehnes proved a simpatico soloist for this music, his slender, silvery tone ideal for Barber’s brand of melancholy lyricism. The Canadian violinist brought hushed intimacy to the brooding Andante while segueing fluently into the more turbulent section. The brief Moto perpetuo finale may not cohere stylistically with the preceding movements, but in Ehnes’ hands it made a decidedly fiery and exciting finale, the soloist throwing it off with faultless bravura and clarity of articulation at a lightning tempo.

Gaffigan led an alert and characterful accompaniment with mostly dedicated playing by the ensemble. Still, it’s unfortunate that the section woodwind players made so little of their opportunities, with only clarinetist John Bruce Yeh bringing first-chair panache to his solos.

Repeated ovations brought the soloist back out for an encore—the final movement (Allegro assai) of Bach’s Sonata No. 3, dispatched in elegant, stylish fashion with immaculate technique. (Ehnes’ set of Bach’s complete solo violin works on the Analekta label is among the finest available.)

Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances closed the evening. Completed in 1940, this was the Russian composer’s final work. Though received indifferently at its premiere, the Symphonic Dances–like the Barber concerto– has slowly wormed its way into the regular concert-hall rotation. Perhaps the leaner, more astringent style is more in synch with our times than the composer’s more lushly Romantic symphonic works.

Gaffigan led a mostly admirable performance, balancing his forces deftly and underlining the offbeat scoring (piano and saxophone). At times, the conductor’s abrupt transitions seemed to jump the beat and take some players by surprise. Also his tempos seemed fractionally rushed, not always allowing the more expansive themes to breathe. Likewise, the central movement could have used a less literal approach with Gaffigan’s bold-faced direction failing to evoke the wistful sadness of this strange spectral waltz.

The final movement went best, with the contrasts surely charted and the CSO bringing ample punchy vehemence to the closing section.

Posted in Performances

Posted Oct 28, 2017 at 9:41 am by Andrew

It’s really a pity that this program was performed only twice. I’m sad I missed my chance to hear it.

Posted Oct 29, 2017 at 12:32 pm by Jon

Johnson’s review is largely on the mark, though the Friday afternoon performance of the Barber sounded unbalanced with Gaffigan’s orchestra repeatedly overpowering Ehnes’s efforts at a nuanced interpretation.