“Play Like Crazy!”: Ligeti series kicks off Friday at UC Presents

In everyone’s life comes a metaphorical gateway drug, something that expands consciousness and opens up new experiences.

For millions, one gateway has been slipped to them via Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey. An essential part of the movie is the unsettling and compelling music that comes out of the soundtrack in the form of excerpts from pieces by composer György Ligeti.

Ligeti is “a gateway to 20th century music,” via the “effect of the sheer sound of his music,” said Amy Iwano, executive director of University Chicago Presents. “Ligeti stands with Cage and Boulez as one of the most influential composers” of the last century.”

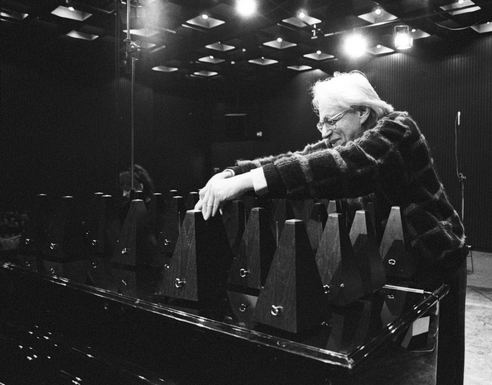

The Ligeti sound will be on display through the University of Chicago Presents’ Ligeti Series, which opens Friday with a concert from the Arditti Quartet, and runs through March 6, 2018, concluding with a recital by pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard.

That sound has reached deep, both far out of proportion to Ligeti’s actual stature in society and to modern classical music’s place in the overall cultural landscape. Credit goes to the dominant cultural form of the last century, the movies. Along with excerpts from some of the composer’s greatest works—Atmosphères, Apparitions, Lux Aeterna, and his Requiem—in 2001, his music has reached listeners through some other, unlikely, movies, like the thrillers Heat and Shutter Island. His influence on classical composers is there too, heard in subtle explorations of timbre and of the possibilities in a massed orchestral sound.

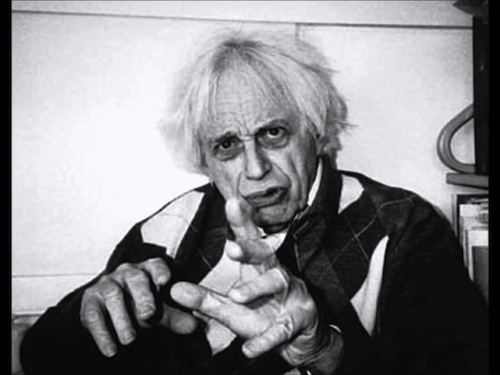

But there is no one who sounds like György Sándor Ligeti, who was a particular type of 20th century artist, an inimitable avant-garde of one.

His singularity as an artist was interwoven with, and substantially driven by, his personal biography. As Aimard pointed out in conversation, “the big stylistic changes came because of big biographical events.”

Ligeti had survived both the fighting of World War II and the Holocaust (his father and brother were murdered in Auschwitz) through the terribly ironic luck of having been conscripted into a labor battalion prior to the large scale round-up of Hungarian Jews. He was kept alive because his physical labor was useful, and managed to desert during battle. He walked back to his original home of Transylvania and hid there until the end of the war.

A supporter of the early, Hungarian communist government, he wrote diatonic, social-realist music through the late 1940s. He gradually soured on communism, and seemingly all forms of authority, as Stalinism began to overtake the country. He wrote music he knew would never be played and put it in his bottom drawer.

His first taste of the Western avant-garde was a bizarre experience; as the Soviets shelled Budapest during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, Ligeti made his way from a basement shelter to listen to a broadcast of Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge—during the fighting the Soviets were no longer jamming radio broadcasts. Electronic music and serial music represented freedom.

The Revolution was Ligeti’s escape. After it collapsed, he made his way to Austria on the last train left before the border closed, in what was a nerve-wracking and terrifying journey. From Austria he went to Cologne, home to the WDR Electronic Studio where Stockhausen and Michael Koenig were splicing their way into the future. Thus began his involvement with the Western avant-garde, which considered Ligeti “a little naive” in violinist Irvine Arditti’s consideration. (He added that Ligeti in turn “was ashamed of his early work.”)

The electronic works he made in the studio, Glissandi and Artikulations, led to his first major statements as a composer, the “micropolyphony” of Apparitions: drone-like music full of tiny, fleeting details and a sensual dissonance that is equally haunting and gripping. Ligeti associated this music with a memory:

“In my early childhood, I dreamed once that I could not find my way through to my little bed … because the whole room was filled up by a fine-threaded but dense and extremely complicated web … Beside me there were other beings and objects hanging up in the vast network: moths and beetles of every kind, trying to reach the light around a few barely glimmering candles … Each movement of the stranded creatures caused a trembling carried throughout the entire system … These … gradually altered the structure of the web … The transformations of the system were irreversible … There was something inexpressibly sad about this process, the hopelessness of elapsing time and of a past that could never be made good again.”

This is Ligeti’s “sheer sound,” as Iwano put it, that continues to draw listeners. It is the emphasis on the aesthetic experience, that permanently separated Ligeti from the dogmatic formalism of his era.

UC Presents’ Ligeti Series is limited to chamber and instrumental music (and a recreation of the WDR studio that will be installed in the Logan Center Stairwell, March 5-8). Still, audiences will still be exposed to his major styles and some of his greatest music, played by the Arditti Quartet, Eighth Blackbird, pianist Aimard, and other prominent musicians.

On the phone from Germany, Aimard said of the repertoire on the program, “sometimes within three minutes you live an experience with a combination of the highest imagination, organization, dramatic strength of the form, the strength of the gestures, and the quality of the craftsmanship. If you like masterpieces in music, well, there are a lot by him!”

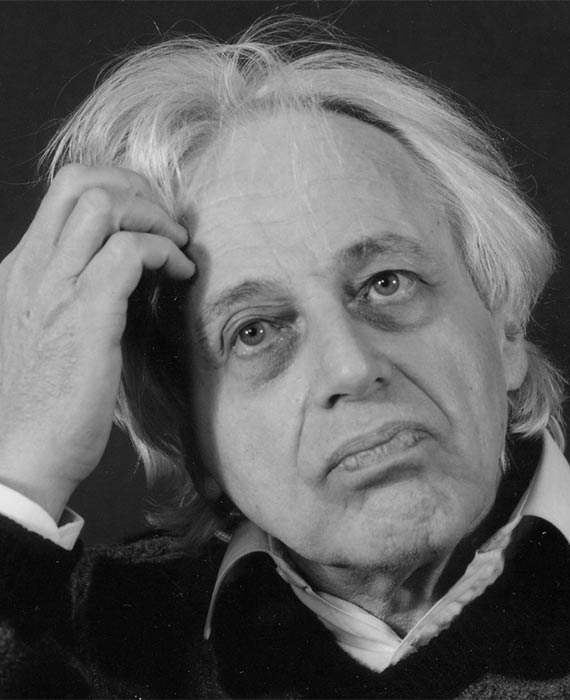

The Arditti Quartet’s opening program will pair Ligeti’s two string quartets with String Quartets No. 2 and No. 4 from Bartók. It is with Bartók that Ligeti begins as a serious composer, and it was with Ligeti’s Bartókian String Quartet No. 1 (1953-54) that the composer found his personal voice. It was also through this piece that the Arditti came to prominence.

Quartet founder and namesake Irvine Arditti, speaking from England, told the story; “[Our agents] were putting on a concert of Ligeti’s quartets, and they couldn’t find a quartet..and they told Ligeti ‘we have this excellent young quartet that can play the music, would you consider it?’ And he said, well, I’ll come to London and listen to them—I think he really just wanted to come to London.

“And so he heard our playing, and he became ecstatic. So we played the concert…Ligeti sort of set us up, and things started snowballing. He was very kind to us and became a friend until he died. He was a very wonderful man and I enjoyed working with him. He was a real human being, a very nice person. He was a vivid man, with a lot of personality…Ligeti was one of the first [composers] to be serious with us.”

Since that opening encounter, the Arditti has recorded Ligeti’s quartets twice, in 1988 for Wergo and then in 1997 as part of Sony’s György Ligeti Edition. “The first Quartet is rather Bartokian and it’s not,” Arditti said,” it’s very Hungarian. It’s a tricky piece to play, it’s classical in form but he wants it very maniacal, faster and faster. He revised the score after working with us.

“He didn’t want to be known for his early music, and the first Quartet was one of the few earlier pieces he let out. I felt he was always a little ashamed of the first quartet, but he didn’t need to be…I didn’t form the quartet to play music like that but like [his] Second Quartet…It’s interesting because later on he came back to a more lyrical style, much like the early pieces.”

The second Quartet, full of atmospheric, skittering gestures and juxtapositions between an escapist lyricism and an unsettling abstraction, is a masterwork of Ligeti’s middle period. With only the four instruments, the piece expresses his disturbingly beautiful dream-like aesthetic.

Arditti added: “I remember him saying things like ‘Play like crazy!’ It was a real unleashing of classical playing—when you play classical music you play within certain limits, you wouldn’t play harshly. Ligeti wanted extremes, extremes of softness where it was barely audible, and loudness where you wouldn’t believe a string quartet could play like that.”

Also on the series will be another early work that Ligeti brought out of his drawer, the Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet, to be played by the Imani Winds. It is notable in that the first five movements were accepted for performance in Hungary, while the dissonance in the last movement was considered “dangerous” and censored.

Through concerts in November and February, audiences will hear his music set with that of his son Lukas, Unsuk Chin, Steve Reich, Christopher Cerrone, and others. On February 16, Third Coast Percussion will organize the Poéme Symphonique, for 100 metronomes. Something of an experimental bagatelle, the Poéme succinctly shows the halves of Ligeti’s art: there is the impish humor that tweaks its nose at the establishment, and the serious, open-ended exploration that sticks in the memory for long after.

The greatest expression of that mix of attitudes is his opera, Le Grande Macabre. It sends up almost the entire history of Western opera, mocks the form’s pretentions to grandiosity, and still works brilliantly as both entertainment and art. But after he finished it in 1977 after 13 years of work, there came what Aimard terms “a huge crisis—Messiaen had got that too after he composed his single opera (Saint François D’Assise)—that was the moment of doubt, the moment of questioning.”

The way out came through absorbing music from all over the world, especially Steve Reich (who had done so much to supplant the previous generation of composers), gamelan music, polyrhythmic music from Africa, the music of another singular avant-garde composer, Conlon Nancarrow, Bartók again, the the pianism of Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans.

After the interim Horn Trio (to be played November 10) came the two books of Études. This is a work that exploded onto the classical scene, won the Gravemeyer Award in 1986, and quickly established itself as one of the greatest masterpieces in the piano literature, an extension of the legacy of Beethoven, Chopin, Debussy, and Scriabin.

Pluperfectly typical of Ligeti’s work, the music sits alone at the apex of musical history, where it seems to have added its own step. The elements of listening that went into the Études appear as memories, and the piece expands what had been possible at the piano. Listeners to the premiere recording had to frequently pick up the CD jewel case to confirm that indeed there was only one pianist playing, when often it seemed like two or more.

Aimard commented, “A creator with enough imagination can transform how an instruments sounds and how one plays it. [The Études] bring the player and listener to reconsider musical parameters. At some moments you don’t know if you hear a rhythm or a texture, at some moments you don’t know if you hear a polyphony. This is a way to challenge the traditional categories.”

Preceded by a lecture-demonstration March 5, Aimard will play 12 of the 18 Études, and complete the March 6 concert with Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” Sonata, Op. 106. He hears both works as “music that in different ways crosses the borders, each…show[s] [where] modern music [was] and what put that in danger. There is a type of creator that needs to challenge the instrument and go beyond. They enlarge the possibilities of the instrument.”

That was one of Ligeti’s most consistent values, something that marked his individual voice. “Later on in his last period,” added Aimard, “his way to integrate extreme differences from the entire world, to integrate with a huge unity, is remarkable. The creator integrates huge influences while maintaining personal artistic integrity.”

University of Chicago Presents’ Ligeti Series opens with the Arditti Quartet, 7:30 p.m. Friday at Mandel Hall. chicagopresents.uchicago.edu.

Posted in Articles