Violinist Hristova provides the highlights in Elgin Symphony’s “Hungarian” program

The Hemmens Cultural Center was at near-capacity Sunday afternoon for the Elgin Symphony Orchestra’s “Hungarian Rhapsody” program—a testament to the work music director Andrew Grams has done cultivating local audiences since taking the ESO reins five years ago.

While none of the music represented was actually Hungarian in origin, the 18th– and 19th-century fare made for an enjoyable afternoon of familiar gypsy-inflected repertoire.

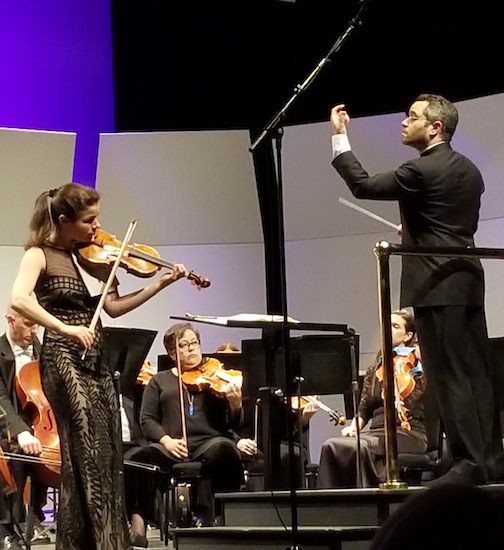

Bulgarian violinist Bella Hristova provided the concert’s highlight as soloist in Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 in A Major. Her silver-toned playing in the opening Allegro aperto was pristine and dignified, and in the Adagio her cantabile lines displayed the grace of a sensitive Mozart soprano. The closing Rondo had a magnanimous quality, its “Turkish” episode (which provides the work’s subtitle) was imbued with requisite flair.

Grams led a serviceable accompaniment, though he would have been well advised to cut down the ESO strings for the task. The legion of supporting violins (six stands of firsts and almost as many seconds) made the orchestral support overly robust and occasionally lumbering, at times dominating the evening’s soloist.

The second half was devoted to Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6. Though less performed than the three the followed, this is a delightful work that more than any of the composer’s other symphonies bears the influence of Johannes Brahms. Indeed it is hard to listen to the triple-meter opening movement and alla breve finale without being reminded of the latter composer’s Symphony No. 2 (not coincidentally also in D Major).

Grams drew an impressive performance from the ESO players. The bucolic Allegro non tanto opening was energetic from first to last, though at times balance was sacrificed in the name of vigor, particularly at louder dynamics. The Adagio was adorned by fine horn playing from principal Greg Flint, and its pained outbursts had a visceral impact.

The symphony’s Scherzo could easily belong to one of Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances, its rhythmic Furiant vitality on a par with any of those popular movements. Grams drew searing playing in the boisterous outer sections, and the more docile contrasting music was pleasingly transparent. The Finale saw impassioned playing from all concerned, though again balancing was sometimes prioritized below force and volume.

The concert opened with Karl Müller-Berhaus’ orchestral transcription of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. The ESO’s strings achieved a rich ensemble sonority in the slow opening section, though the clarinet cadenzas that punctuate it were weak and tentative. The bombastic finale went with a manic panache, with the ESO’s brass were stentorian in their descending scales.

Grams deserves much credit for the work he has done building up the ESO. Though his unbuttoned style is clearly a winner with many audience members, sometimes his informality goes a bridge too far—as with encouraging the audience’s applause between movements of the Dvořák symphony. Some loosening of the standards of concert etiquette may not be such a bad thing, but not when they distract from the music itself and make for an overall less cohesive performance.

The Elgin Symphony Orchestra’s next classical program presents the Vivaldi Gloria and Mozart Requiem February 10 and 11 at the Hemmens Cultural Center. elginsymphony.org

Posted in Performances