Chamber Music Society closes season with major works in a minor key

It’s a dangerous gambit to play three pieces in the same key in one evening. Such overexposure can breed monotony, even in music by the greatest composers.

Luckily, no such monotony seized “Tempest in C minor,” the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center’s final local concert of the season, which took place Monday night in the Harris Theater. Still, the missing ingredient in the performances, ironically, was the tempestuousness highlighted in the title.

Pianist Inon Barnatan, violinist Augustin Hadelich, and cellist Clive Greensmith started things off with Beethoven’s Piano Trio in C minor, Op. 1, no. 3. As the opus number might indicate, this is the earliest of Beethoven’s C minor works. The piece was so unsettling to Haydn, when he heard it, that he urged Beethoven not to publish it.

The performance was striking, then, for its uncommon tenderness and beauty, with little of the apparent angst that troubled Haydn. Instead, a general air of delicacy hovered over everything, punctuated by rare and very short bursts of intensity.

Like Beethoven’s other early piano trios, this piece is really for piano with violin and cello accompaniment. And so, the tone was mainly set by Barnatan—in his serene delivery of the first movement’s main theme, and by his translucent ripples upwards in the minuet.

Hadelich and Greensmith nonetheless made the most of their few moments in the spotlight, such as the one minor-key variation in the second movement. Greensmith brought a subdued melancholy to this, and Hadelich added a surprising sweetness.

Brahms’s String Quartet in C minor, Op. 51, no. 1, was the evening’s centerpiece performed by the Calidore String Quartet. The piece is a far cry from the Beethoven—dense and digressive, where Beethoven was streamlined.

It also poses some problems for its players. Brahms’s thick textures mean a minimum of opportunities for any individual member to shine. Cohesion counts above all, and the Calidore Quartet was immaculately cohesive.

The major flaw of their interpretation was a tendency towards slackness. They did well in the most overtly vigorous moments of the outer movements, particularly in the finale. But Brahms also builds suspense through repetitive figures that skitter softly among the instruments. These consistently lacked tension in the Calidore’s performance.

The hardest movements to execute are the middle two. With few climactic moments, one really has to milk these, or the movements as a whole can seem uneventful. The Calidore Quartet played these prettily, no doubt, but with far too much restraint.

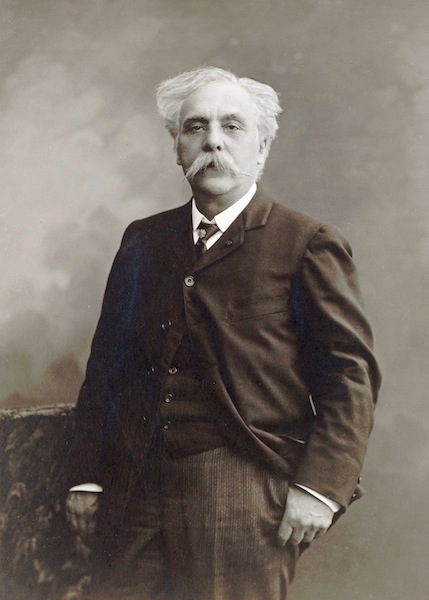

The evening closed with Gabriel Fauré’s Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor. Barnatan, Hadelich, and Greensmith retook the stage, joined by violist Matthew Lipman.

Their performance was the most satisfying of the concert, with the musicians bringing great intimacy to the piece’s more introverted moments. The melody for muted strings that opens the trio of the scherzo can often sound indistinct. But Hadelich, Lipman, and Greensmith gave it a clear shape, without compromising its gauzy, otherworldly sound.

There was no shortage of grandeur in the big moments, even in unexpected places. The opening chords of the Adagio are often just backdrop for the string melodies unfolding in front of them, but Barnatan let them ring out like church bells.

In the finale, all three strings danced nimbly around the piano and each other, during the more playful portions. But when their parts united, their sound swept across the hall like one majestic wave.

Posted in Performances