Heggie’s acclaimed “Dead Man Walking” to receive Lyric Opera debut

In the words of the Rolling Stones, you can’t always get what you want. But sometimes, what you get is better.

Lotfi Mansouri, general director of the San Francisco Opera, had something specific in mind in 1997 when he approached composer Jake Heggie and playwright Terrence McNally about writing an opera for the company’s 2000-2001 season. He envisioned something celebratory and fizzy, a festive kick-off for a new millennium. Die Fledermaus, anyone? The Barber of Seville?

What did he get? Dead Man Walking.

Beginning Saturday night Lyric Opera presents its first performances of the opera inspired by the best-selling nonfiction book by Sister Helen Prejean, a Catholic nun, about her work with condemned men on Louisiana’s Death Row.

(Published in 1993, it also inspired a 1995 movie directed by Tim Robbins starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn. Sarandon won an Oscar for her portrayal of Sister Helen.)

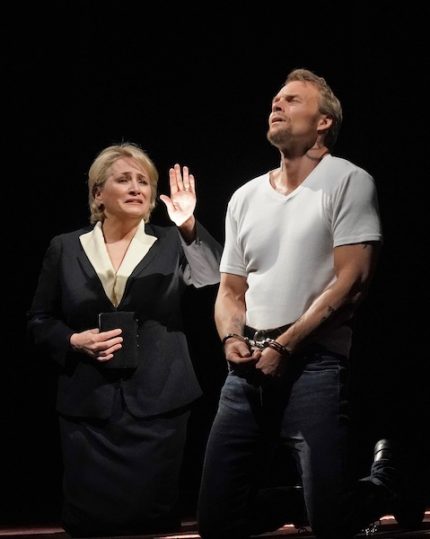

Patricia Racette will make her role debut as Sister Helen in this Lyric production with Ryan McKinny as Joseph De Rocher, the condemned murderer to whom Sister Helen ministers. Susan Graham, who created the role of Sister Helen in San Francisco, appears as Mrs. De Rocher, Joseph’s mother. Leonard Foglia directs the production he created in 2002.

“You can imagine,” said Heggie, recalling the meeting when he and McNally told their plans to Mansouri. “Lotfi had wanted something fun. Champagne! Bubbles! Maybe a comedy for the new millennium!”

As it turned out, McNally wasn’t interested in champagne and bubbles. When he suggested Dead Man Walking instead, Heggie was instantly intrigued. They were already far along on the project when they met with Mansouri. At an event for Lyric patrons earlier this month, Heggie described the scene in the general director’s office.

“Lotfi said, ‘So, what do you have?’ Heggie recalled. “And I looked over at Terrence, and I said, ‘You tell him.’

Once the shock wore off, Mansouri was intrigued.

“He said, ‘I would never have thought of that, but what a brilliant idea,’ “said Heggie. “Yes, Dead Man Walking.” Lotfi was on board from that second.”

Since the opera’s premiere in October 2000, opera companies large and small have also climbed aboard. By next season, when the Metropolitan Opera presents Dead Man Walking for the first time, the opera will have received more than 70 productions in venues ranging from major opera houses such as the Teatro-Real in Madrid and Germany’s historic Dresden SemperOper to university music schools. (In 2015 Northwestern University Opera Theater presented its Chicago-area premiere in a riveting production.)

That’s an astonishing record for a contemporary work, especially since Dead Man Walking was Heggie’s first opera. A professional pianist, he took a job in 1994 with the San Francisco Opera’s press office, writing speeches and news releases. On the side he wrote songs that were performed and recorded by such leading singers as Frederica von Stade, Renée Fleming and Susan Graham.

“Jake’s music is so emotionally immediate,” said Graham. “It speaks to something in you that you don’t even know you have. It’s so evocative of nostalgia and feelings. And to think that this incredibly rich piece–Dead Man Walking, so honest and musically ingenious–was his first opera. It’s like it came from outer space.”

“Writing an opera was new to me,” said Heggie, soft-spoken and relaxed in a one-on-one interview at Lyric a few weeks before rehearsals began. “But [working in the San Francisco Opera press office] I had been around the creation of two operas—Dangerous Liaisons [by Conrad Susa] and Streetcar Named Desire [by Andre Previn]. I’d spent a lot of time at rehearsals and talking to the artists about the process.”

McNally is one of America’s leading playwrights but, like Heggie, he was a novice at writing opera. He proved to be an ideal collaborator.

“I was so lucky to have Terrence McNally,” said Heggie. “He was so generous. He had never written a libretto before, but he loved opera and it inspired him deeply in his own work. He said his job was to set up scenes and characters that inspire music. He wanted to make sure that the music took flight. He said, ‘If it isn’t inspiring music, then we’ll have to change it, we’ll have to fix it. You should just be able to write and let it pour out of you.’ That was a huge gift.”

Working with Sister Helen, who turned 80 this year, was also a gift. A lively woman with a wicked sense of humor and a warm Louisiana accent, she cheerfully admits that she “didn’t know boo-scat” about opera when Heggie and McNally first approached her. But the fight against capital punishment had become her life’s work. Part of that work is bearing witness, telling the world what a state-sanctioned execution in the dead of night in a notorious prison really looks like.

“Coming out of that execution chamber,” she said in a phone interview from her home in New Orleans, “when I had just watched a human being rendered defenseless and killed, and everybody thought it was a great idea…I knew I had to get that story out. The idea is to reach as many people as we can, to bring them close to that reality, which is a secret ritual they will never see.”

That’s why she wrote her book. And why she allowed it to be turned into a film and an opera.

“The one thing I had been told,” said Sister Helen, “if you’re thinking of signing a contract with anybody doing another art form with your book, be sure you trust them.” She worked closely with Sarandon and Robbins on the film’s script, which, among other changes, turned the two inmates in her book into a single, compelling composite character.

“It was very trusting, very collaborative,” said Sister Helen. “From that experience of the film, I knew that when you have good artists you can trust, they can put your work out there. As soon as I heard there was going to be an opera, I had to trust that we were going to be working with people who were trustworthy. And Jake and I got to be close. You’ve got to give them permission, take a risk, turn it over to them.”

Sister Helen staunchly opposes the death penalty, but the opera, like the film is not a one-sided polemic against capital punishment. We feel the pain of everyone involved, including the grieving parents. We can understand the thirst for vengeance but also the hope that forgiveness might help heal broken spirits. Sister Helen confronts her own fears and missteps as she tries to offer comfort to everyone involved.

Set in Louisiana in the early 1980s, the opera opens with the brutal, senseless murder of two teenagers by De Rocher and his brother. A troubled young man with a tough-as-nails attitude, he is guilty beyond a doubt and scheduled for execution at the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

Sister Helen is working with children in a New Orleans housing project when she agrees to exchange letters with men on Death Row. What starts as an episodic, long-distance relationship deepens into a close bond as Sister Helen visits De Rocher and becomes his spiritual advisor. She meets his family and tries to comfort the embittered parents of the teenagers he killed. She walks to the death chamber with him and watches him die. She comes to believe that capital punishment is immoral, even when guilt is beyond doubt. We are all God’s children, she argues, and, as such, deserve to be treated with dignity. Taking responsibility for our crimes and accepting appropriate punishment, yes. State-approved punishment by death, no.

Heggie’s music is often driven and unsettled, but its lyrical lines draw us deeply into each character’s emotional terrain. In a slow, bluesy aria, De Rocher recalls the pleasures of a warm night with a pretty girl down by the river. Driving to meet De Rocher for the first time, Sister Helen muses about her spiritual journey. There are some light moments. In a rollicking rock and roll duet, Sister Helen and De Rocher bond over their shared worship of Elvis Presley. In an electrifying sextet, the bereaved parents and De Rocher’s mother attack Sister Helen. She can’t possibly know what it’s like to bear a child, to fail a child, to bury a child, they say. “I’m sorry. So sorry” is her repeated, anguished refrain.

“What’s great is that Terrence and Jake have been very thoughtful in how they unfold who this person is,” said Racette about the role of Sister Helen. A strong dramatic actress, Racette has appeared in Menotti’s The Consul and Poulenc’s La Voix Humaine at Chicago Opera Theater in addition to leading roles at Lyric. “So many aspects of the opera are about how Sister Helen listens, and the music sets the tone for that. She is a woman of action, she’s this definite person. But her position to be receptive is ever-present in the role.”

Graham, who first appeared as Mrs. De Rocher in 2017 at Washington National Opera, sees Sister Helen and Mrs. De Rocher as poles apart.

“They’re on opposite sides of the emotional fence,” she said. “Sister Helen has to be the strong one, she has to hold everybody up. She has to empathize with every single person she encounters. The mother, however, is more single-minded. She wears her feelings on her sleeve. She has compassion for the parents of the victims; she understands how they can hate her son. But mainly she just sees her son as a little boy. She’s so deeply in denial I don’t think she ever really accepts that he’s guilty.”

Mrs. De Rocher can seem emotionally fragile, but she is no delicate Southern magnolia. Pregnant too young, too often, with no money, she’s had a hard life. Graham, who was born in Midland, Texas, sees Mrs. De Rocher in that context.

“I play her a little harder-edged than I’ve seen her played,” said Graham. “I am Southern—well, okay, Southwestern, Southern-adjacent. I’ve been around a lot of people who have informed how I see this character. I see her as a little angrier.”

Conductor Nicole Paiement, principal guest conductor of the Dallas Opera, makes her Lyric debut with Dead Man Walking. Based in San Francisco, she led a 15th anniversary production of the piece at the city’s Opera Parallele, a small company she founded to explore contemporary and rarely performed operas. Earlier this year she conducted the world premiere of Heggie’s newest opera, If I Were You, at the San Francisco Opera’s Merola Opera Program.

“Jake Heggie’s music integrates storytelling in a very complete way,” said Paiement. “Both the orchestral and vocal writing are involved. As a conductor, I appreciate having this other vehicle—the orchestra—to tell the story. Instead of just accompanying the singers, the orchestra is actively telling the story along with the singers.”

Dead Man Walking opens 7:30 p.m. Saturday and runs through November 22. lyricopera.org

Sister Helen has donated her archives to DePaul University and comes to Chicago every April to work with DePaul students. Her religious order, the Sisters of St. Joseph, has centuries-old ties to the Vincentian priests, the order that founded DePaul in 1898

Posted in Articles