Newberry Consort mixes the sacred and secular with flair in “A Mexican Christmas”

If Baroque + Christmas = Handel in your mind, then Friday night’s concert at Grace Lutheran Church in River Forest would have been a welcome taste of less familiar fare.

There the Newberry Consort teamed up with EnsAmble Ad-Hoc for the second year in a row for a Mexican Christmas concert.

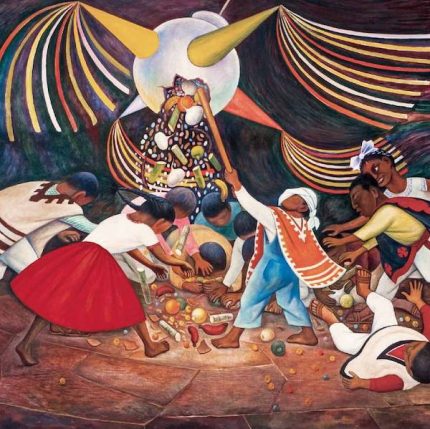

The premise was similar to last year’s event: juxtapose music that might have been performed in the 17th century on either side of the doors of the Convento de Nuestra Señore de la Encarnación in Mexico City—sacred music sung by the nuns inside and secular music sung by villancico bands outside.

This juxtaposition was made particularly theatrical at the concert’s outset. The EnsAmble Ad-Hoc entered singing “La Rama” with directors Francy Acosta and José Luis Posada leading the vocalists and instrumentalists respectively. The singing soon broke out into dancing, but was interrupted by sounds of Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla’s “Christus natus est nobis” wafting from the choir loft, sung by an all-female segment of the Newberry Consort led by co-founder Ellen Hargis.

The other co-founder, David Douglass, and some of the male members of the Newberry Consort performed with the villancico band. The divided ensembles stayed in separate locations for most of the concert—the villancico band at audience level in the apse, the convent choir above.

The groups performed in alternating sets, with vocal music broken up by the occasional instrumental interlude, including arrangements by Posada himself. This concert structure was likely intended to underline the contrasts between the two genres, but ended up also emphasizing the similarities.

The contrasts were chiefly in text and timbre. The villancicos often consisted of humorous dialogue between named shepherd and farmer characters. Particularly irreverent were the guineo, negrito, and negrilla the ensemble sang—songs by and about Mexico’s African descendants. These included Gaspar Fernandez’s “Dame albriçia, mano Antón,” whose singers have heard that Jesus was born in Guinea, and plan to travel there to bring him snacks.

The sacred music, on the other hand, was likely to have more abstract conceits, such as in Padilla’s “Voces las de la capilla,” which includes puns on solfege syllables (the words “la,” “mi,” and “re” sung on those pitches) and a thirty-three note passage depicting Christ’s death at age thirty-three.

These differences translated into the performance styles. The EnsAmble Ad-Hoc emphasized the individual timbre of each singer’s voice and the different Baroque guitar variants in the band, and involved selling the text’s jokes, such as in describing frightening the Christ child in Padilla’s “Ah, siolo Flasiquiyo!”

The Newberry Consort’s style emphasized clean intervals, a more blended group sound, and earnest text delivery.

But earnest doesn’t mean staid. One of the consistent facets of New World music of this era—sacred and secular alike—is its rhythmic vitality. The Newberry Consort didn’t have strumming guitars and pounding drums behind them (like the EnsAmble Ad-Hoc did) but their music was just as syncopated, with additional metrical shifts that they negotiated not only smoothly but stylishly, as in the aforementioned “Voces las de la capilla.”

Another similarity between secular and sacred genres of music was that both were often structured around an estribillo (refrain) that alternated with coplas (verses), which might spotlight a soloist.

The soloists in the convent choir needed to weave seamlessly in and out of the contrapuntal texture. Contrarily, the vocal soloists in the villancico group had to characterize their brief roles. And the instrumental soloists were required to keep all of the pieces full of color and energy—especially in the display episodes in their interludes. All performed these tasks splendidly.

The composer most prominently featured on the program was Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla, who moved from his native Spain to Puebla in 1620. He is far from a mainstay in the Baroque repertoire, but certainly deserves to be. The concert was not just enjoyable as a theatrical experience; it was valuable as a showcase for an under-appreciated master.

The listed program ended with the convent choir descending to join the villancico band in a rendition of Juan García de Zéspedes’s “Convidando está la noche.” Then, everyone let their hair down. Both ensembles sang an encore of “Mi Burrito Sabanero” in the nave, while the audience clapped along.

As a final treat, a giant piñata was brought out and audience members were encouraged to take turns beating it. The alarming ferocity with which they did so suggests that the holiday break is coming none too soon.

The program will be repeated 7 p.m. Saturday at St. John Cantius Church in Chicago, and 3 p.m. Sunday at the First United Methodist Church in Evanston.newberryconsort.org

Posted in Performances