Kalmar, Grant Park Orchestra scale the tragic heights of Mahler’s Ninth

The final weekend of July is invariably an artistically fortuitous time for Grant Park Music Festival audiences as well as musicians. What could be an inconvenience—Lollapalooza chasing the orchestra inside and underground to the subterranean confines of the Harris Theater—is instead a boon, allowing listeners to appreciate the Grant Park Orchestra’s fine musicians even more sans the electronic intermediary of amplification.

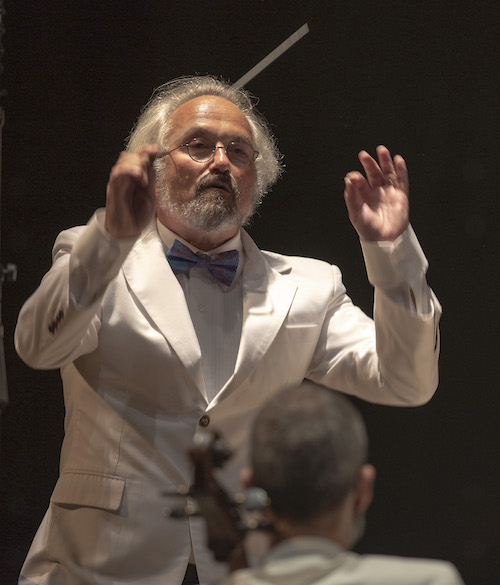

Carlos Kalmar returned to the podium Friday night in his first festival appearance since being sidelined by a positive Covid test June 22 and having to bow out of three programs he was scheduled to lead. Happily, the festival’s artistic director and principal conductor was back in hale and energetic health, leading the evening’s sole work, Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, with characteristic vigor and intensity.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is outwardly classical in form, cast in four movements. Yet Mahler detonates traditional structure in this, his last completed work: two massive slow movements frame a rustic Landler and agitated scherzo, the entire edifice expanded to epic proportions.

Written a year before his death at age 50, the Ninth is Mahler’s greatest achievement, an epic death-haunted journey that reflects the composer’s unsettled psychological state amid premonitions of his imminent passing. The sense of the center not holding and a departure from the joys and sorrows of earthly existence permeate the score. The first two notes of the opening motif that dominates the first movement almost seem to say “Leb wohl” (farewell).

The Ninth is also a work of its time and place, with the foreboding and bleak pessimism of fin de siecle Vienna reflected in Mahler’s score as palpably as in Egon Schiele’s distorted landscapes and the dark obsessions and death fixations of Arthur Schnitzler’s stories

Kalmar led an inspired Mahler Ninth on the same stage 13 years ago, in the work’s belated festival debut. The knowledge that this would likely be the conductor’s final performance of this work with the Grant Park Orchestra—he will depart after the 2024 season—bestowed an additional sense of occasion.

Yet, as was the case in 2009, this performance took awhile to gel. In the opening Andante Comodo, the playing was largely polished and responsive with tempos well-judged. Yet the first movement often felt like a work in progress—straitened in dynamics and expression, and somewhat surfacey as if awaiting an extra rehearsal or two to polish details more finely. Kalmar guided the music fluently and climaxes were imposing but too many moments of existential dread felt underplayed and glided over. Near the end of the movement, the performance began to find its footing with playing of greater power and grip.

It was strangely reassuring to see that this dark score can still unsettle people, as witness several walkouts after the end of the long first movement. You were maybe expecting On the Beautiful Blue Danube?

The inner movements were exemplary, with the music vividly characterized as the performance came into focus and gained intensity. Kalmar took the second movement at a snappy pace, imbuing the Landler rhythms with a jaunty, al fresco air; the antic, frenzied middle section provided biting contrast.

The Rondo-Burlesque provided the right galumphing, subversive irony. Woodwinds were superb here, and Kalmar elided the schmaltz in the lyrical middle section, rounding off the movement in a manic burst of frenzied desperation.

The performance rose in estimable fashion to Mahler’s epic finale. Kalmar took the movement at a slightly quicker pace than usual, which sharpened focus on the unfolding tragedy. From the initial statement of the main theme, Kalmar and colleagues unerringly conveyed the sense of leave-talking and the valedictory essence of the music. The conductor maintained taut tension throughout the nearly half-hour movement, and the iteration of the main theme resounded with increasing power and sonorous impact. As the music descended to a hushed farewell, the coda’s fragmented phrases—rendered with beautiful, barely audible playing by concertmaster Jeremy Black and string colleagues—bestowed a ray of solace as the music slowly, inexorably ebbed away to silence.

Mercifully, the intermittent crying of a baby in the house did not spoil the hushed atmosphere of those final notes. Who brings an infant to an indoor concert of Mahler’s Ninth? And why was it even allowed?

There were a few intonation lapses and passing ensemble slips along the 85-minute journey. But for the most part, the Grant Park Orchestra members played gloriously under Kalmar’s attentive direction, from the shrieking piccolo to the basses’ imposing foundation. Contributing standout solo work were concertmaster Black, flutist Mary Stolper, harpist Eleanor Kirk and, especially, principal horn Jonathan Boen who was terrific (along with his section colleagues) in his myriad solos—clarion, full-bodied, nostalgic and eloquent as required.

__________

Carlos Kalmar’s inevitable spoken introductions bother me less than they do some, though his populist MC approach can occasionally come off as simplistic and (unintentionally) condescending for a musically sophisticated audience. Such was the case Friday night when he summed up Mahler’s vast, complex work by saying, “It doesn’t end so well.”

That’s an awfully trite and reductionist take on a multi-layered cornerstone masterwork with a vast range of expression and emotion. And while darkness and a sense of last things tend to dominate, often the best performances of the Ninth find a degree of consolation amid the tragedy of the final movement—as this performance achieved.

Sometimes it’s better to just let the music speak for itself.

Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 will be repeated 7:30 p.m. Saturday at the Harris Theater. gpmf.org

Posted in Performances