A dazzling desert season bears rich fruit with Santa Fe Opera’s Debussy, Monteverdi

SANTA FE: Santa Fe Opera has served up a connoisseur’s season this summer, with only one obvious crowd-pleaser on offer in Puccini’s Tosca. At the top of a rotation perhaps better suited to critics than general audiences is Claude Debussy’s masterpiece Pelléas et Mélisande, last mounted here in 1977. Seen at its third performance Friday night, this enigmatic work from 1902 proved an antithetical followup to the company’s first performance of Tristan und Isolde last season.

The libretto of Pelléas, adapted almost directly by the composer from the symbolist play by Maurice Maeterlinck, also concerns an adulterous love triangle in a fairytale land. Golaud, the son of Arkel, the old blind king of Allemonde, finds a strange girl named Mélisande weeping in the forest and marries her. She mostly shuns him, preferring his half-brother Pelléas, younger son of Geneviève, who joined this seemingly cursed family long ago. Golaud grows jealous of the liaison between the title characters and kills Pelléas, leading to Mélisande’s death.

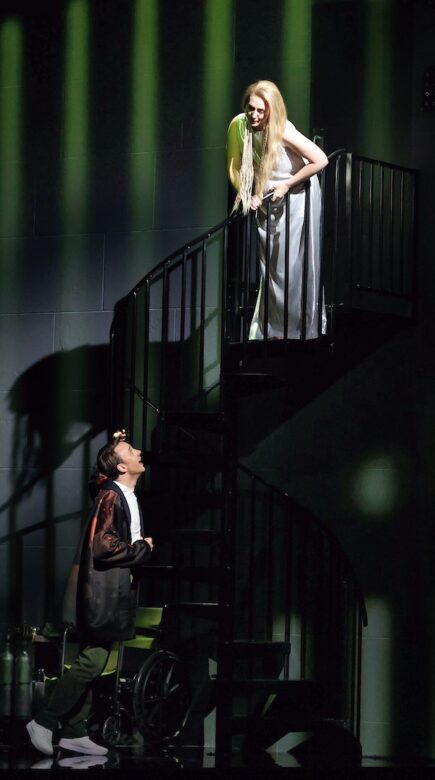

The production overseen by Netia Jones situates the action in some kind of post-apocalyptic bunker, indicated by industrial fans, video monitors, and spiral staircases. A large glass terrarium, with plants growing underneath garish lights, rotated in place. A small river flowed across the front of the stage, paralleling the water channel that separates the pit from the house in Santa Fe Opera’s Crosby Theater. Mirror images abounded, especially in the use of supernumerary actors who doubled several of the characters.

Where Tristan is an epic journey of high emotion and orchestral sweep, Pelléas is three hours of mostly affectless ambiguity and contradiction. Samantha Hankey deployed her airy mezzo-soprano and excellent French as a consummately beautiful Mélisande, giving dramatic weight and clear declamation to Debussy’s chant-like vocal writing, devoid of any melismatic decoration or aria-like solo moments. Only some of the role’s higher stretches posed challenges for the American singer, in a fine company debut.

English baritone Huw Montague Rendall, also heard in Santa Fe for the first time, made an ardent Pelléas. The opera has no tenor roles, creating a bass-dominated vocal gloom in the casting. Rendall’s voice had a nervous tension, especially at the top end, but he captured the awkward, almost adolescent nature of the role. Veteran mezzo Susan Graham was a delight as Geneviève, in spite of some volume limitations in the contralto reaches.

Former Santa Fe apprentice singer Zachary Nelson stepped in to replace Gihoon Kim (still listed in the program) as Golaud, with excellent results. His snarling tone gave the right explosive edge to this violent character, complemented by the woolier sound of bass Raymond Aceto’s sage Arkel. Treble Kai Edgar brought strong acting skills and generally fine singing to the role of young Yniold, and was especially sympathetic in his often terrifying exchanges with his father, Golaud.

Music director Harry Bicket presided over an exquisitely nuanced, often hushed rendition of this ethereal score. Lush strings swooned, alternating with many fine solos from the woodwinds, as well as occasional louder sweeps crested by the large brass section. The Act I chorus of distant sailors, another tribute to Wagner, added a rare moment of vocal complexity.

Jones’s costume design featured shifting colors, showing the evolution of the characters. More impressively, video imagery projected onto the whole of the back wall of Jones’s set evoked elements from the libretto, including the thick, sun-blocking forest, mysterious waters, and the lighthouse by the ocean. All in all, this static production heightened the feelings of anxiety and suspicion that run throughout this complex opera.

Another feather in the cap of Robert Meya, general director of Santa Fe Opera since 2018, was the company’s first production of Claudio Monteverdi’s seminal Orfeo, premiered in 1607. Santa Fe Opera’s only other staging of a work by this ground-breaking composer, often designated the father of opera, was a 1986 Coronation of Poppea. This quirky Orfeo, full of surprises musical and otherwise, featured as the summer’s final premiere on Saturday evening.

This production was to have showcased the Santa Fe Opera debut of Rolando Villazón in the title role. The Mexican tenor had to withdraw from opening night after sustaining a back injury at the final dress rehearsal Thursday evening. In a statement, Villazón specified that he was hurt during “one of the flying sequences,” and the cause was the harness he was suspended from in Act II. Rather than adapting the production without this effect, the premiere went ahead with a cover singer. (The Santa Fe Opera press office later clarified that because Villazón “was prescribed physical rest until July 31, there wasn’t an option of ‘adapting the production without this effect’.”)

Kudos to Luke Sutliff, a former Santa Fe Opera apprentice, for saving the day. A baritone, he had enough upper range to make a go of the role, and his resonant tone reverberated at climactic moments, like the forceful iterations of the line “Rendetemi il mio ben, tartarei Numi!” He somehow negotiated the complexities of the character’s showpiece aria, “Possente spirto,” while hanging on the aforementioned wires, even doing backflips at one point.

Soprano Lauren Snouffer made a striking company debut as La Musica, who sings the opera’s introduction. She also sang Speranza, the allegorical character of Hope who leads Orfeo to the gates of the underworld, where he must obey Dante’s words in Inferno and abandon her.

As the Messenger who announces the death of Orfeo’s wife, Euridice, the striking mezzo Paula Murrihy deployed a razor-sharp straight tone. The Caronte of bass James Creswell and Plutone of baritone Blake Denson, both full-voiced, were also piped into the house by the sound system, a sleight of hand given away by a soft scratch the first time the microphone was turned on. The rest of the cast was filled out with apprentice singers, to mixed effect, with the mournful Euridice of soprano Amber Norelai and plangent Ninfa of mezzo Lucy Evans standing out.

Harry Bicket showed the depth of his conducting range at the podium, having led Pelléas, from almost three centuries later, just the previous night. Unexpectedly, given Bicket’s early music specialization, this opera fared worse in terms of ensemble coordination. Part of this was likely due to the inexperience of the young cast, but some blame goes to Nico Muhly’s eccentric modern-instrument orchestration of the score, heard in its world premiere. Surprise cameos by bass clarinet, glockenspiel, contrabassoon, piano, and celesta were entertaining, but Muhly’s preference for offbeat textures, often musically confused, wreaked havoc for some on the stage.

Director Yuval Sharon, known for innovative stagings since his mobile opera Hopscotch in 2015, has made Orfeo into a sort of ode to live music in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Snouffer’s La Musica, costumed as a recovering terminal patient and nearly bald (costume design by Carlos J Soto), arose from a hospital bed at the start of Act I. She joined the wedding celebration and appeared throughout the opera, much like the signature instrumental ritornello that accompanies her introductory aria.

The set for Act I, a sort of burial stupa filling the stage, backed by a magical New Mexico sunset vista, opened up by wires as Orfeo made his way beneath it into a bizarre, fungal-themed underworld for Act II. This striking transformation required the performance to be given without intermission. In a pleasing nod to the opera’s premiere at the court of Mantua, brass players performed the opera’s arresting opening fanfare near Igor Stravinsky’s statue on the terrace to the right of the theater.

The flying effect for “Possente spirto” was visually arresting at first, with lighting by Yuki Nakase Link and hallucinatory, smoky projections by Hana S. Kim. Just because one can do it, however, does not mean one should. There is no dramatic reason for this gimmick, which lasted far too long: Orpheus does not float across the Acheron into hell, he is ferried there by Charon. The resulting injury to the production’s star singer only underscored this ill-advised artistic choice.

While Music has come back to life, as in the opera, reminders of the temporary death of the art form during the Covid lockdowns remained. Orfeo was blindfolded while he led Euridice forth from death, savvily foreshadowed by the game of blind man’s buff he was made to play at the wedding in Act I. When he removed the blindfold to make sure she was following him, she was snatched back to the underworld. Her voice, no longer living, now came to her husband only through a golden phonograph he carried forth.

Pelléas et Mélisande runs through August 18, with a few cast changes. Orfeo runs through August 24. santafeopera.org

Look for more coverage this week from Santa Fe Opera at The Classical Review.

Posted in Performances