A neglected American masterpiece and a commanding solo debut at Grant Park

With about three weeks of concerts remaining for the 2023 edition of the Grant Park Music Festival—Carlos Kalmar’s penultimate season—the series’ principal conductor and artistic director is resolutely ticking the boxes of worthwhile if unfamiliar works from the diverse, and apparently bottomless, bag of symphonic repertory he is eager to share with listeners at Millennium Park.

Wednesday’s concert by the Grant Park Orchestra under his direction brought another such program of fascinating discoveries to the Jay Pritzker Pavilion.

Its centerpiece was the near-forgotten Negro Folk Symphony by American composer William Levi Dawson, never before played at the festival. The work, composed in 1934 and revised in 1952, has also completely escaped the attention of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. (Mei-Ann Chen and the Chicago Sinfonietta brought Dawson’s work to the CSO’s home in 2021).

That neglect is astonishing, given the quality of Dawson’s only symphony and the provenance of its creation. The Alabama-born Dawson began work on it while studying for his master’s degree at the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago, while playing trombone in the Civic Orchestra of Chicago.

Dawson founded and directed the music school at the Tuskegee Institute whose choir he went on to make internationally famous, singing his arrangements of spirituals on which his reputation chiefly rests.

While on tour with the chorus in New York, he showed the manuscript of his Negro Folk Symphony to conductor Leopold Stokowski, who suggested ways in which he might expand it. In 1934, when the African-American composer was 35, Stokowski gave four premiere performances with the Philadelphia Orchestra, one of which was broadcast. The symphony was an instant success with both public and press, and by rights should have been taken up by orchestras across the land.

But it was not to be. After scattered performances in the ‘30s, the work tumbled from the radar. Not until after its pioneering first recording in 1963, under Stokowski’s direction, did the Negro Folk Symphony resurface. That recording is based on the revised version incorporating authentic rhythmic patterns Dawson gleaned from a trip to West Africa in 1952.

The Grant Parkers’ energized, fully committed performance on Wednesday night revealed a first-rate symphonic work utterly undeserving of its long neglect—a piece comparable, if not superior, in quality, to orchestral works by the much-better-known William Grant Still and the now-ubiquitous Florence Price, with whom he must have rubbed collegial elbows in Chicago.

Dawson said his composition was an attempt to convey the vernacular musical elements that had been lost when black Africans fell into bondage outside their homeland—an emotionally charged piece no white composer could have written.

The symphony’s three movements, each bearing a descriptive title — “The Bond of Africa,” “Hope in the Night,” “Let Me Shine!” — draw on traditional black spirituals (which Dawson preferred to call “Negro folk-music”) for their inspiration and actual content. Rather than merely quoting singable tunes, Dawson elaborates them with great musical sophistication and a formal rigor that evolves organically. The late-Romantic idiom recalls that of Dvorak, himself influenced by African-American vernacular music. Nothing jumps out at you as being uninspired or superfluous.

While falling just shy of the rhapsodic intensity of the Stokowski recording, Kalmar’s reading was more than sufficient to convince one of the symphony’s many merits and to regret that the gifted Dawson never went on to compose another. The orchestra sounded thoroughly rehearsed in this unfamiliar, and by no means technically easy, score. Each movement carried considerable impact, particularly the central “Hope in the Night,” its plaintive English horn solo soaring in the muggy evening air over a martial tread in the plucked strings. The dramatic moment near the end, when the entire orchestra takes up the theme, was enough to induce goosebumps. The pavilion folks leapt to their feet in approval at the end.

Kalmar began the concert with another first festival performance of music by another, somewhat better-known, 20th century black composer—Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s The Bamboula (1910). The British composer (son of a doctor from Sierra Leone and a white Englishwoman) based his lively curtain raiser on the same dance tune, then popular among enslaved people in the Caribbean, many listeners recognize from Louis Moreau Gottschalk’s piano piece of the same name. It is splendidly orchestrated and came off to rousing effect on this occasion.

The sound enhancement system now captures and projects the aural likeness of the Grant Park Orchestra with greater presence, clarity, balance and warmth than what one recalls from recent seasons—a fine handmaiden to what Kalmar has achieved in terms of orchestra building during his tenure.

Tucked between the Coleridge-Taylor and Dawson scores was Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto, an established masterpiece that, believe it or not, Grant Park had not touched before 2004, when Kalmar and friends belatedly introduced it to festival-goers during their inaugural season at the Pritzker Pavilion.

The soloist was the greatly gifted young cellist Zlatomir Fung. Now 24, the Juilliard School alumnus and Ravinia Steans Institute fellowship winner is the first American and youngest artist ever to have won first prize at the International Tchaikovsky Competition, cello division, in Moscow. Local audiences were left slack-jawed by his artistry at last season’s University of Chicago Presents series, and his eloquent Elgar underscored that favorable first impression.

With practically everyone else on stage wearing shirtsleeves, Fung looked downright uncomfortable in his dark suit, but he certainly sounded completely at home as he confidently poured out Elgar’s noble lyricism. Nary a wailing siren or mewling child could faze him on a sticky night at Millennium Park. His intonation was impeccable, his tone warmly expressive, his feeling for long-breathed phrases altogether sensitive. He dispatched the skittering, catch-me-if-you-can scherzo to a fare-thee-well, and the inwardness of his final diminuendo all but made time stand still.

The festival’s sound system balanced the cellist’s burnt-umber tone against orchestral sonorities Kalmar shaped most attentively and lovingly, never indulgently.

Mark well the name Zlatomir Fung. You will be hearing a good deal from this already-accomplished cellist in the years to come.

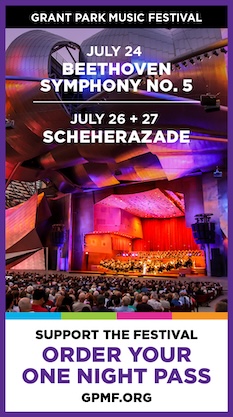

The Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus under Gerald Steichen will present a program of Broadway favorites, 6:30 p.m. Friday and 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Jay Pritzker Pavilion. gpmf.org

Posted in Performances