New CEO brings a fresh optimism as Lyric Opera opens 70th season

The first official day of work for the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s new boss isn’t until October 14. Yet John Mangum, the 49-year-old arts administrator who is the opera company’s incoming general director, president & CEO, is already on the job.

In addition to making himself available for interviews, Mangum will be in the house Saturday night as Lyric Opera opens its 70th season with Verdi’s Rigoletto.

“I’m incredibly excited about the challenge and the opportunity,” said Mangum, who is leaving a six-year tenure as executive director and CEO of the Houston Symphony to move to Chicago and tackle the top job at Lyric.

Mangum noted that due to opera’s long advance planning time, his impact on programming wouldn’t be visible for a while yet. “I think you’ll start to see my fingerprints in 2027-28,” he said. “The first season that I will be wholly responsible for planning is 2028-29.”

While diplomatic about commenting on the record of his unpopular predecessor Anthony Freud, in a wide-ranging interview Mangum answered questions with candor, which bodes well—or at least better—for a new era at Lyric Opera.

Mangum has his work cut out for him. In the 2010-2011 season, the year Freud was named CEO, Lyric Opera presented 68 performances in an eight-opera season (which has been its tradition). Last season there were just 40 performances of six operas, a 43% decrease since then. Yet even with the sharply decreased performances, the company wound up having to draw $22 million last year from its endowment fund (and $14 million in 2022) to meet expenses.

Mangum has a record of achievement—and stable financial stewardship—in his ascending career positions, and colleagues past and present speak well of him. Prior to his Texas post, Mangum served as president and artistic director of the Philharmonic Society of Orange County, director of artistic planning at the San Francisco Symphony, and artistic administrator of the New York Philharmonic. He worked at the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Hollywood Bowl for eight years in similar positions.

Still, some eyebrows were raised at Mangum’s appointment due to his lack of background in managing an opera company—even a small regional company—never mind one of the largest companies in the country.

Mangum acknowledges that he may have been a surprise choice for that reason but says that the essentials of managing any large arts organization are broadly similar in scale and responsibility.

“In Houston we do about 170 performances a year, “ he said. “In Chicago [at Lyric] you’re now doing between 40-60 performances.

“A main part of [leading] a performing arts organization is that they are defined by massive complexity and many different stakeholders—all of whom need to be listened to and addressed. So I think there is a lot of similarity between a symphony orchestra and an opera company.”

He also emphasized that, for better or worse, a crucial element of leading any large arts organization in the 21st century is development—bringing in the cash from grants, wealthy benefactors and legacy donors, all of which are down from previous years.

“These jobs have increasingly taken on a component of development work,” said Mangum. “Supporting the work that your organization does means bringing in contributed revenue. And that is critical whether you’re running an opera company, a symphony orchestra or a theater company. That’s a set of skills that is transferable.”

He demurred at commenting on the specific problems of Lyric at a time of financial shakiness, low ticket sales, and what is widely viewed as an extended period of artistic decline. Rather, he placed Lyric’s current challenges more broadly in the context of American companies generally.

“I think all opera companies were hit especially hard by the pandemic,” he said. “Those of us who were not employing a large numbers of vocal artists and a chorus were able to figure a pathway back. The way back was longer for opera companies.”

“I think the more fundamental challenge that was maybe accelerated by the pandemic is the fundamental question of what does an opera company in 2024 look like? The cities that these companies serve have changed demographically pretty significantly over the last, say, fifty years, The sources of funding have changed over time as well.”

“So how do you change the resources that are available to you and maximize the amount of work that you’re putting on for your audiences? That’s the key challenge. It’s not unique to Lyric but its a challenge that Lyric is going to be focused on over the coming years.”

On a related topic, many patrons have been put off by the increased politicization of Lyric Opera in recent years—as reflected in statements of support for Black Lives Matter and instituting stringent DEI quotas—as high as 50% in casting and production and higher still for new hires.

While Mangum supports the principle of diverse casting, he said he is less convinced by rigid numerical quotas.

“I don’t really think that way in my approach,” said Mangum. “I think that the work that you’re putting on stage has to be reflective of the community. But what is paramount is artistic quality.

“And I don’t think there is any tension between the two. You can reflect your community without any kind of artistic compromise.”

While Mangum may not have been associated with opera companies professionally, the art form has been his great musical love from his youngest days.

Asked about favorite performances, he mentions a San Francisco Opera performance of Marriage of Figaro with Renée Fleming as the Countess in the Mozart bicentennial year. Mangum is a big fan of David Hockney’s productions including the artist’s Magic Flute and his well-traveled Turandot, which originated at Lyric Opera.

“The Die Frau ohne Schatten that [Hockney] did at San Francisco last season was remarkable. I saw the Tristan twice in L.A. I love the painterly environment he creates for these works. While he’s a visual artist, he also has a great ear and insight into music.”

He said he was also much taken with Peter Sellars’ “Tristan Project,” which presented Wagner’s opera in a highly visual concert realization with video by Bill Viola.

“That was an eye-opener in terms of a way to do opera in concert that was entirely dramatically satisfying,” said Mangum. “It was just as satisfying as seeing a fully staged production because of the video and the work Peter did with the singers; it was really a staged production except that the orchestra was on the stage and not in the pit.”

“I think that’s something we will want to explore at Lyric as ways to bring pieces that are less often performed or contemporary and presented in that kind of concert format.”

In terms of more recent productions that he thought were especially successful, Mangum said he was greatly impressed by David McVicar’s Medea at the Met with Sondra Radvanovsky.

“That was just sort of a peak experience of an artist at her pinnacle,” he recalls enthusiastically. “It was as if Cherubini knew her and wrote the piece as a vehicle for her. The production was incredibly powerful in focusing attention on the drama that was unfolding but also had moments of real operatic spectacle.”

One of the disappointments at Lyric in its recent history has been the short shrift given to American operas of the past. Yes, the company has done more contemporary American operas in recent years, which is laudable—even if the inspiration seemed more centered on the pieces’ political bent than their musical or artistic quality. But great American operas of the past have been entirely ignored.

“Well, I’m not making any promises. I haven’t even started yet!” Mangum said with a laugh. “But I love Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah. Susannah is a wonderful, wonderful work.

“I think it’s important for a company of Lyric’s size and importance to continue that commitment to commissioning new work by American composers, like [Missy Mazzoli’s] The Listeners this season. Yet I do think there is a worthy canon of American operas that predate the contemporary day that are worth exploring.”

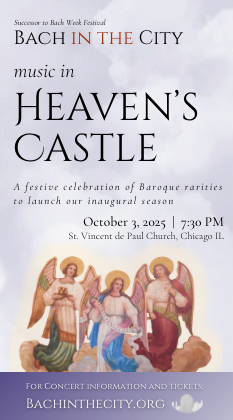

Baroque opera has also been a relative rarity at Lyric, which is something Mangum would like to take a fresh look at as well.

“The Baroque opera question is a great question. It’s near and dear to my heart. I wrote my dissertation on Italian opera seria.”

“Doing more Handel operas would be lovely but also some lesser known composers like Rameau and Gluck. Orfeo gets sunlight every so often and Iphigénie en Tauride is a wonderful piece.

“But I’ve got a little time to think through how that repertoire balances. So I think the earliest would be 2027-28. But I would love to see Lyric doing, with some regular cadence, more pre-Mozart, 18th century opera.”

“The basic answer to the question is we have to make sure we have the right balance [each season] and we have to make sure we have the financial resources to do anything that we want to do—whether it’s Baroque opera, American opera, contemporary opera, or a big piece from the canon like Tristan or Don Carlo. The key thing is that the fundamentals have to be strong, so that we can make these kind of commitments to really exploring all the interesting artistic highways and byways that are out there.”

Along with the lack of stars in the past decade at a company that has traditionally presented the great singers of the day—Maria Callas made her Chicago debut in 1954 in Lyric’s first season—the company’s recent penchant for inflicting bizarre revisionist productions on local audiences has clearly taken its toll at the Lyric box office. (See Christopher Alden’s disastrous Flying Dutchman from a year ago for a recent example.)

While Mangum stipulates that he hasn’t seen many recent productions at Lyric, he feels that the company is overall “at a very high level artistically.” “You’re not going to always be 100%,” he said. “Every so often there is going to be something that for whatever reason just doesn’t work.”

“My approach is that composers know what they want,” said Mangum. “They lay it out pretty clearly in the music and the libretto. The productions that I like the best—like that Medea—are the ones that really get to the heart of what’s in the piece.

“Sometimes those productions follow what’s laid out and sometimes they may challenge the piece a little bit. A really good director can explore those tensions in a way that is still satisfying for all audience members.

“My fundamental position is I want what’s on the stage to be at the absolute highest level,” said Mangum. “From the first note of the prelude, the orchestra sounds great, the singers are incredible. That has to be at the core—so that people leave the theater feeling that they had a satisfying artistic experience.”

Lyric Opera of Chicago opens its season 7:30 p.m. Saturday with Verdi’s Rigoletto. Starring Igor Golovatenko, Mané Galoyan and Javier Camarena, the production runs through October 6. lyricopera.org

Posted in Articles

Posted Sep 12, 2024 at 4:21 pm by GCMP

I realize that there are fixed production costs, etc. but it is not that much of a stretch to go back to 8 operas, say 5-6 performances each. A better repertory mix is thus possible.

Then scratch all the weird concerts etc. Rebuild the subscription series, and end the weird breaks caused by the Joffrey. The Joffrey performances should be intermixed into the regular weekly opera offerings, and not require the opera to do nothing at all during ballet weeks.

And keep up the restoration of great singers, that’s what we really want! Prima la Musica . . . the productions should be respectful—-not some artistic drivel from an egotistical director who thinks they know more than Mozart.

Posted Dec 09, 2024 at 11:12 pm by Hugh

Find the people who are asleep at the switch – – I canceled my subscription after 20 years and nobody ever called to ask why or to ask me to reconsider.