Sinfonietta pays worthy tribute to Ives with UChicago retrospective

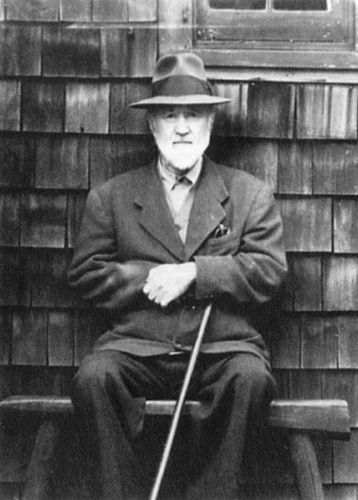

The 2024-25 season marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Charles Ives, a man far ahead of his time and one of America’s most singularly inventive composers. But you wouldn’t know it looking at this year’s programming from Chicago’s largest classical institutions, which are not offering a single example of the modernist New Englander’s music.

The Chicago Sinfonietta successfully made up some of the difference Saturday night at the University of Chicago’s Mandel Hall with their one-night-only “Charles Ives’ America,” an educational, multimedia concert focused on the composer, and highlighted by a vibrant account of his Symphony No. 2 led by music director Mei-Ann Chen.

Ives composed this work between 1897-1902, the same years during which Sigmund Freud was at work on and published The Interpretation of Dreams in Vienna.Both Ives in this symphony and Freud in his dream book seemed to arrive at analogous insights about the potential for familiar elements, when combined in surprising ways and unexpected contexts, to convey meaning and evoke early memories, a potential that was fully on display in Saturday’s performance.

The opening Andante moderato had nostalgic whiffs of Dvořák before segueing attacca into the Allegro, where traditional American folk idioms are integrated seamlessly with an expansive Romanticism. The central Adagio cantabile had a similar wistful quality, with Chen leading the orchestra to ardent cinematic climaxes.

The Lento maesto fourth movement is essentially an introduction to the concluding Allegro molto vivace, where “Turkey in the Straw” sounds perfectly natural as a dolce counterpoint. Principal cello Ann Griffin offered a limpid solo in dialogue with principal flute Janice MacDonald shortly before the work’s close, which is a jarring dissonant lurch, not unlike waking up from a dream.

The Sinfonietta’s performance of this under-heard work was largely accomplished, even if string pitch grew increasingly errant as the performance progressed. Chen is an ebullient stage presence, but often her conducting devolves into a generalized, all-purpose enthusiasm. Nonetheless, this was overall a committed outing that made the neglect of Ives’ turn-of-the-century symphony all the harder to comprehend.

The first half paired Ives with the music of George Walker. The evening opened with Walker’s Folksongs for Orchestra, whichcreatively orchestrates the spirituals “My Lord, What a Morning” and “Peter Go Ring Dem Bells,” deconstructing the former while capturing the jubilant feel of the latter.

Chen brought out the nuance of Walker’s imaginative treatments, and baritone Sidney Outlaw offered stirring a cappella renditions to introduce each movement, the first of much impressive work throughout the night.

Outlaw’s other contributions included “The Circus Band,” the last of Ives’ early Five Street Songs, and—as a prelude to the symphony—“Three Cheers for the Red, White, and Blue” and “Wake Nicodemus,” which are featured in the score. Outlaw offered all of these selections with authoritative gravitas, and it was helpful to hear the original songs before encountering the uses Ives makes of them.

Ives’ Three Places in New England followed the Walker songs, eventually. LaRob K. Rafael of WFMT was on hand to serve as a genial host, and he and Chen offered a play-by-play of what was on hand in Ives’ triptych. While some of this context was helpful, particularly illustrating how Ives builds his dense orchestral textures (anticipating Ligeti by decades), this introduction was nearly as long as the work itself.

“The St. Gaudens in Boston Commons” had a hazy memorial feel, and was accompanied by projected images of the title sculpture, which depicts the 54th Massachusetts Regimen, the second all-black unit in the Union Army. Ives’ creates a sense of a battle scene viewed through mist, but Chen’s heavy-handed approach was too literal for such atmospheric music.

“Putnam’s Camp, Redding, Connecticut” had a raucous, festival air, with Chen presiding over the barely controlled sonic chaos. A dreamier section, depicting a child wandering off from the festivities was again handled too directly by Chen, who was at her best whipping up a storm in the return of the carnival music.

“The Housatonic at Stockbridge” trickled evocatively, with Ives’ capturing the murkiness of the flowing river with ambiguous harmonic undulations. Chen led the violins in a rapt theme on the G-string amidst the aquatic swirling, which was also accompanied by video of the river. Inserting songs and poetry between the movements of Three Places was a truly disruptive element, particularly after the overlong introduction to the work.

Overall, the event’s background aspects were enhancing, however, particularly Outlaw’s vocalism, sensitively accompanied by pianist Steven Mayer. Peter Bodganoff’s visual accompaniment to the works on the first half was unobtrusively evocative and added to the complex picture of Ives the program successfully captured.

The Sinfonietta has adopted the unfortunate but increasingly widespread approach of replacing printed programs with one-page leaflets with a QR code linking to more information online. If an organization goes in this direction, the physical handout must include the works’ movements, which were even missing from the online version Saturday.

The Chicago Sinfonietta performs Michelle Isaac’s Moshe’s Dream, Valerie Coleman’s Opus Serena with bassoonist Monica Ellis, and excerpts of symphonies by Brahms, Mendelssohn and Mahler March 13 and 16. chicagosinfonietta.org

Posted in Performances

Posted Feb 27, 2025 at 9:01 am by GCMP

No longer providing proper printed programs is a disservice in the long run as the electronic versions rarely provide all the information one used to get. AND, you can only refer to your phone at intermission or afterwards.

The Joffrey can’t even hand out a cast list, so you can’t easily tell who is dancing.