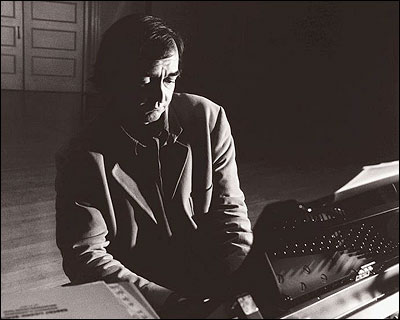

Pierre-Laurent Aimard brings out the unpredictable in varied recital

More often than not, the Sunday afternoon piano recital is a pleasant, predictable affair. Many audience members are pianists themselves and come with scores in hand to follow along with what artist X is traversing on stage.

Such was likely not the case at Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s Symphony Center recital Sunday. The French maverick pianist offered a program varied and unusual enough that even a music librarian would have had a hard time keeping up.

Aimard has been playing the music of French composer and mystic Olivier Messiaen since he was a child and in fact, was a student of Yvonne Loriod, Messiaen’s wife. Messiaen’s eight Préludes pour piano, a student work from 1928-9 and his first published pieces, are rarely performed and only give a hint of the wonders to come in his later piano music.

The influence of Debussy, who had only died a decade earlier, permeates these preludes, but Debussy as re-imagined through a funhouse mirror by a young composer who merely used the harmonic vocabulary of late Impressionism as one trainstop along the way to finding his own voice.

Aimard made a surprisingly strong case for the forty-minute collection, which took up the entire first half of the afternoon’s program, particularly as experienced within the context of his overall program.

By bookending Messian’s Eight Preludes and Ravel’s Miroirs, an Impressionistic tour de force, around two forward-looking Chopin pieces—the Barcarolle in F-sharp Major, Op. 60 and the Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 31—Aimard presented a fascinating aural trajectory. We were reminded not only of how Romantic both Ravel and Messian really were, but also how much more innovative Chopin could be than we often give him credit for.

Aimard’s Chopin was never of the flashy variety so commonly heard. Rather, he clearly views Chopin as a precursor to Late Romantic and contemporary music, instead of a mere culmination of the Romanticism that preceded him. As such, quirky qualities of this music that many pianists would overlook were brought out to considerable effect.

It was particularly fascinating to hear how Chopin and Ravel both treat the subject of water: Chopin in his attempt to aurally portray the canals of Venice in the Barcarolle, and Ravel in Une barque sur l’océan (“A boat on the ocean”).

Although Messiaen was a lifelong bird lover and bird watcher, he had not yet begun his elaborate musical transcriptions of specific birdcalls, let alone figured out how to incorporate them into his music at the time that he wrote the Préludes. Yet even there, the suite opens with La colombe (“The dove”), which attempts an abstract rather than an aural portrayal. In this, Messiaen draws a parallel to Ravel in his Oiseaux tristes (“Sad birds”) within Miroirs.

Encores are generally considered to be opportunities for the most familiar and beloved works of the repertoire to be paraded about amongst increasingly sustained applause, but again, not at a Pierre-Laurent Aimard recital. Here, you are treated to a contrasting and revealing mini-marathon of piano pieces of our own time, including György Kurtág’s Hommage a Berényi Ferenc 70, Ligeti’s Musica Ricercata, George Benjamin’s 4 Piano Figures, and Elliott Carter’s Matribute.

Posted in Performances