Nagano, Vonsattel and CSO fete Bernstein in style

If you’ve been living in a cave for the past six months, you might be unaware that the current music season marks the 100th birthday anniversary of Leonard Bernstein (August 25, 1918).

The achievements of Bernstein, who died in 1990 at age 72, as conductor and populist advocate for great music are many, important and secure. Perhaps his most important legacy is his pioneering 1960s set of the complete Mahler symphonies, which did much to launch the massive popularity of Mahler and make his music a permanent concert-hall mainstay.

Bernstein’s achievements as a creative artist are more open to debate. The celebrated composer-conductor only wrote one indisputable masterpiece, West Side Story, and that came early in his career, with his limited subsequent output wildly uneven in quality.

Yet in our culture, a cult of personality, fame and celebrity are more important than substance or actual accomplishments–even in the world of dead classical composers. So, while the vast majority of other worthy 20th-century American composers continue to go wholly ignored by the classical powers that be (excepting Gershwin and Copland), Bernstein’s music is being feted everywhere this season, with substantial festivals on tap this summer at Ravinia, Tanglewood and elsewhere.

Even the Euro-centric Chicago Symphony Orchestra has gotten on the bandwagon and this season has already provided superb performances of the Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront and the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story.

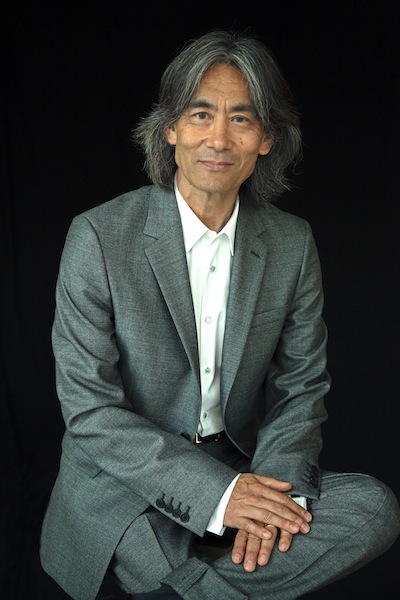

Thursday night gave us the third and final installment of the CSO’s “Bernstein at 100” mini-festival, with his Symphony No. 2, “The Age of Anxiety,” led by Kent Nagano.

Bernstein’s Second Symphony is the best of his three works in the genre—more mature and polished then the youthful and endearing “Jeremiah” and less self-indulgent than the numbingly pretentious “Kaddish.”

The Second Symphony (completed in 1949) takes its inspiration and title from W.H. Auden’s expansive poem, “The Age of Anxiety.” Crafted in two movements of six sections, the symphony is programmatic in its depiction of four boozy, lonely characters in a Third Avenue bar who embark on a quest for meaning. Bernstein’s long-winded note for the premiere is reproduced in the CSO program and makes one agree with his later change of heart that “The Age of Anxiety” should best be listened to as pure music without the programmatic minutiae.

And that music reflects a kind of postwar ennui and emptiness—a seeking of solace and spiritual meaning in a world that seems to no longer offer much of either.

Ultimately, the symphony’s slick eclecticism and facile flash add up to less then the sum of its parts. Yet “The Age of Anxiety” is unmistakably Lenny in its urban edge, audacious scoring, jazzy drive and occasional excess.

Nagano, music director of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, was an informal Bernstein student, and considers him his most important mentor. The American conductor’s sympathy for Bernstein’s idiom was clear and complete Thursday in the CSO’s first complete performance of “The Age of Anxiety” in two decades.

Nagano directed a full-blooded performance that brought out the roiling, mercurial essence of the music–from the nocturnal urban loneliness and brooding 12-tone desolation of “The Dirge” to the whipcrack rhythmic drive and metallic, percussion-led tuttis that point the way forward to On the Waterfront and West Side Story. There was no irony at all in the concluding “Epilogue,” with the rising lyrical theme of “newly recognized faith” sumptuous and sentimental in the best Bernstein style.

Gilles Vonsattel made a most impressive CSO debut in the symphony’s prominent keyboard part. The Swiss-American pianist kept his role in proper scale, skirting spotlight-grabbing concerto bravura, yet always fully serving the score’s lyrical and dramatic demands as needed. Vonsattel was especially inspired in putting across the jazz-based essence of Bernstein’s piano writing—in the “Masque” the pianist was less concerned with speed than style, tossing off the skittering syncopations with a light, kitten-on-the-keys panache that was delightful and felt just right.

Music of Wagner and Schumann framed the Bernstein symphony.

The evening led off with the Siegfried Idyll. Wagner famously wrote this confection—utilizing themes from his opera Siegfried—as a surprise for his wife Cosima’s birthday (December 24), surprising her Christmas morning, with the musicians positioned on the stairs of their home performing a private premiere.

Nagano led a spacious, warmly affectionate account. Apart from a brief oboe slip, the playing conveyed the music’s cozy domesticity, with the lovely flute and clarinet solos adding to the romantic glow.

Schumann’s “Spring” Symphony concluded the program. Amazingly not played by the orchestra downtown in 18 years, Schumann’s First Symphony is a work of almost unclouded cheer and youthful high spirits.

Nagano and the orchestra conveyed the essence of this music in a solid, middle-of-the-road performance. The conductor’s tempos tend to be on the stately side and at times, the performance would have benefited from greater vitality and rhythmic acuity. (The Scherzo was hardly molto vivace, as marked.)

Still, this was a conscientious and largely engaging performance, even if it missed some of the music’s essential charm.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Saturday. cso.org; 312-294-3000.

Posted in Performances