Lyric Opera’s powerful “Dead Man Walking” comes to life with searing impact

Few composers have enjoyed the kind of triumphant success with their first opera that Jake Heggie has with Dead Man Walking. Premiered at San Francisco Opera in 2000, Dead Man has become, arguably, the most performed of contemporary operas, racking up two recordings and innumerable performances around the world in less than two decades.

On Saturday night, Dead Man Walking made its belated Lyric Opera debut. And with a largely inspired cast and effective production, the powerful opening-night performance delivered all of the opera’s drama with searing impact.

The opera, with a libretto by Terrence McNally, was adapted from Sister Helen Prejean best-selling 1993 nonfiction book about her work with condemned men on Louisiana’s Death Row. (The book also inspired the 1995 movie of the same name starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn.)

The disturbing opening minutes set the scene as two skinny-dipping teenagers are brutally murdered (and the girl raped). Joseph De Rocher, who is unquestionably guilty, is convicted of the crime and sentenced to death. He begins to correspond with Sister Helen, a good-hearted but somewhat unworldly nun who works mostly with children. When Sister Helen meets Joseph, he asks her to be his spiritual advisor, meaning she will be the one to minister to him as he enters the death chamber. Yet Helen is questioning the strength of her own faith and whether she is up to dealing not only with Joseph’s distraught mother and the damaged, grieving parents of the victims, but of Joseph himself, an unrepentant killer who refuses to acknowledge his guilt.

In addition to being the most Catholic opera since Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites, Dead Man Walking is a failsafe piece of musical theater—perfectly constructed with moments of wry humor amid the serious drama. There are a wealth of well-drawn characters throughout its large cast, and the narrative moves inexorably to its devastating denouement in the execution chamber.

McNally’s libretto deals with a host of important issues in an intelligent yet non-polemical way—is capital punishment moral, what is the nature of faith and forgiveness, and how can one find any spiritual meaning in a world of unspeakable crimes and violence.

Yet it is Heggie’s rich, extraordinarily assured score that really sells the rather downbeat story. His eclectic style naturally incorporates the vernacular, gospel music and church hymns mingling with solo arias and choruses for large ensemble. Dead Man is almost as much straight theater at times as opera, yet the dialog moves seamlessly from speech to musical recitative and back again with ease and facility. At its best, Heggie’s score rises—as with the sextet and closing ensemble of Act I—to masterly heights.

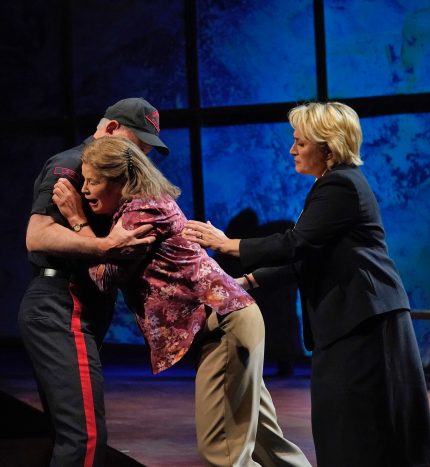

Among the three principals, Ryan McKinny made a knockout Lyric Opera debut as the condemned murderer, Joseph De Rocher. The American singer didn’t set a shackled foot wrong as the embittered, heavily tattooed convict– distrustful of Sister Helen’s motivations, cynical about his imminent execution, and steadfastly refusing to admit his guilt in the crime. McKinny is a first-rate actor, wholly inhabiting the hard-as-nails-convict. Yet his pained expressions reveal the conflicted humanity of this brutal yet tormented man, building into Joseph’s devastating emotional breakdown when he finally confesses his guilt to Sister Helen.

Vocally, McKinny was just as strong. His bass-baritone has a bit of grain in it—apt for the role—but his voice is surprisingly flexible and McKinny floated high soft notes with supple tenderness.

Susan Graham created the role of Sister Helen at the opera’s San Francisco premiere 19 years ago, and her vivid portrayal did much to ensure the opera’s success. In this Lyric production she makes a seamless transition to the role of Mrs. De Rocher, Joseph’s mother. The Texas-born mezzo delivered the finest vocal moments of the evening, and her deeply felt, sensitively shaded farewell to her son was almost unbearably moving.

Like McKinny, Graham fully conveyed her character dramatically–a single working-class woman whose blind love for her criminal son makes her refuse to hear his desperate desire to confess his guilt. Graham’s take on Mrs. De Rocher feels more gritty and lived in than von Stade’s inimitable brand of vulnerable charm. Graham is almost unrecognizably dowdy and hard-edged in this role, chain-smoking cigarettes and nervously tapping her foot (just like her son) as she awaits the parole board’s decision.

The wild card among the principals was Patricia Racette as Sister Helen. Racette is one of our finest singing actresses and, for the most part, did an admirable job in this role debut. Her low-lying soprano handled all the notes of this mezzo part without any transcription, and her voice was able to fill the house in the ensembles, some passing wobbly moments apart.

Dramatically, Racette seemed to be finding her way into the role at times opening night. While the lighter moments seemed rather forced, she made the major peaks register, and Helen’s final moment with Joseph was emotionally wrenching. Still, even with her estimable acting, Racette’s Helen seemed a bit too mature and world-weary from the start, making the nun’s spiritual struggle and character trajectory feel less plausible. (Frederica von Stade, then 55, turned down the role of Sister Helen at the 2000 premiere, believing herself to be too old for the role, and played Mrs. De Rocher instead.)

Racette’s ability to create a believable character wasn’t aided by some of the costuming; Sister Helen’s sharply tailored, black-and white business suit and swept-back hair made her look more like a briskly sympathetic corporate CEO than a rural Catholic novice.

In this widely traveled production, Michael McGarty’s sets starkly paint Louisiana’s Angola prison with massive cage-like metal structures, towering side pillars and a raised high platform in the middle; the facade morphs smoothly into a paneled courtroom wall for the parole hearing.

Elaine J. McCarthy’s projections and period photos evocatively place the rural Louisiana milieu, as does Jess Goldstein’s costumes (the exception noted above). The scenes are atmospherically lit by Brian Nason.

In a big supporting cast of large voices, Whitney Morrison proved ideal casting as Helen’s colleague, Sister Rose. The Ryan Center alumna brought a big, gleaming soprano and sympathetic persona to Helen’s friend and sisterly confidante, their voices blending gratefully in the Act II duet.

One of the elements that gives Dead Man Walking its dramatic strength is the humanity of Terrence McNally’s libretto. No characters are reduced to cardboard types or mere caricature (as is so often the case in today’s highly politicized arts world). The bitter parents of the murdered teens receive their due—asking Sister Helen why she focuses all her compassion on the murderer and none on the families of the victims.

As the parents, Lauren Decker, Allan Glassman, Talise Trevigne and Wayne Tigges made a strong and well-sung quartet. Tigges, as a very dyspeptic Owen Hart, may want to take his angry characterization down a notch in order to make the father’s apology to Helen for his previous outburst seem more believable.

It was wonderful to have Gordon Hawkins—Porgy in Lyric’s 2008 Porgy and Bess—back as George Benton. Big of voice and physique, Hawkins showed his still-booming baritone and etched a nicely layered portrayal of the skeptical yet compassionate prison warden.

Clay Hilley contributed a fine characterization as the passive-aggressive prison priest Father Grenville. The young singer possesses a daunting Heldentenor, and his huge voice soared over the massed ensemble in the prayer that closes Act I.

Christopher Kenney made a nice cameo as the motorcycle cop who lets Sister Helen slide on a ticket. Eric Ferring and Ethan Warren were dramatically credible as Joseph’s two younger brothers. Michael Black’s male chorus of prisoners brought force and polished vocalism to the ensemble scenes. And actors Miles Borchard and Ari Kraiman set the opera effectively into motion as the murdered teen victims.

Director-lyricist Leonard Foglia is a frequent Heggie collaborator, having helmed the world premiere of Moby-Dick and directed the current Dead Man staging elsewhere. That experience showed in the fluent scene changes of the quick-moving action and the consistent momentum that pressed the narrative forward.

The sole directorial misstep was having Sister Helen emerge from behind the murdered teenagers’ car immediately after the killings as she sings her entrance hymn. The audience really requires a brief space—emotionally and visually—to process the violent act and separate it from the ensuing, light-filled scene of happy nuns and children. Perhaps that was an attempt by Foglia to bridge the contrast, but it had the opposite effect and made it seem for a jarring second that Sister Helen was peeping on the teens in the woods.

There was only one obvious opening-night glitch but it was truly an epic fail. In the final execution scene, after the glass is lowered in front of him, Joseph’s voice was suddenly massively amplified, sounding like some omniscient intergalactic being. Whatever the intent, the artificial sound was way overdone, distorting Joseph’s final words and distracting from the action at the climactic moment of the evening.

After a somewhat droopy opening Prelude, conductor Nicole Paiement quickly got the evening on track and made a most impressive company debut. A specialist in contemporary opera, Paiment kept fine coordination with the singers, handled Heggie’s mercurial score with assurance, and built to the big musical and dramatic peaks with sure, focused direction. The ensemble closing Act I was overwhelming in sonic amplitude and dramatic impact.

Astoundingly, Paiement is only the second woman to conduct a Lyric production in the company’s 64-year history (Emmanuelle Haim led performances of Handel’s Giulio Cesare in 2007.) With all the gifted female conductors currently before the public, let’s hope that a company that likes to pride itself on “relevance” finds a way to make that a more regular occurrence.

Dead Man Walking runs through November 22. lyricopera.org

Posted in Performances

Posted Nov 03, 2019 at 6:25 pm by Lorin Pritikin

Your review is spot on. Despite some misses, I agree that it was a powerful production with excellent acting and singing. I particularly did not like the first scene with the children and Sister Helen—as you said. But the rest of the production redeemed itself.

Posted Nov 04, 2019 at 11:17 am by H D

From my own reading, I surmised that Sister Helen would have been in her 40’s when she first met De Rocher. She joined her order in 1957 and started her correspondence with the death row inmate who the character De Rocher is based on in the early 1980’s. I loved Pat Racette’s interpretation of the role.

Posted Nov 07, 2019 at 12:49 am by BB

Spot on but the final scene was perfect Wednesday night. The voice was slightly distorted to create a separate room (off limit death room) intercom feel. The heart monitor might have been just a bit too loud but overall the bugs were worked out.

My only issue was some of the sister Prejean high notes that just didn’t seem to always fit. Is that an issue with english operas or was it just the score? Otherwise, the best staging I’ve seen in quite awhile. Great performance. Could’ve skipped the nudity too but it did add to the emotional roller coaster. Great review!

Posted Nov 29, 2019 at 10:43 pm by indianbadger

I liked the fact that the Opera began with the crime. That made the opera’s anti death penalty theme more effective. For me, this was one of the most memorable productions I have seen. This whole season has been wonderful. Both the end of act one and two were emotionally wrenching.