Weak music fails to ignite a compelling story in Lyric Opera’s “Fire Shut Up in My Bones”

Few operas enjoy the kind of warp-speed development of Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones. Premiered at Opera Theatre of St. Louis in 2019, the work was quickly fast-tracked the following year by the Metropolitan Opera, which commission a larger and expanded version. Lyric Opera and Los Angeles Opera jumped on the bandwagon as the Met’s coproducers.

The revised opera opened the Met’s 2021-22 season in September. On Thursday night the production came to Lyric Opera with most of the New York principals reprising their roles from last fall.

Fire Shut Up in My Bones is based upon journalist Charles M. Blow’s memoir of the same title about his growing up in rural Louisiana. The opera begins with the angry Charles as an adult determined to kill the relative who molested him as a child. The action flashes back to his childhood as “a boy of peculiar grace,” his life with his loving if volatile mother Billie and four macho older brothers, Charles’ abuse, awkward adolescence, college days and eventually coming to terms with his past and “leaving it all behind.”

The story is compelling and hugely appealing. And while depicting an African-American family in a rural milieu, there is a universality in this coming-of-age journey from childhood pain and teen loneliness to adulthood and personal reconciliation.

Unfortunately, the central problem with Fire Shut Up in My Bones is that the music by composer Blanchard is almost unrelievedly bland and never rises to the emotional peaks of the storyline. A jazz trumpeter who has written film scores and one previous opera, Champion, Blanchard’s score is cast in a kind of noodling jazz-piano lounge style. For long stretches, the score offers little more than a kind of plodding, pleasant inconsequentiality, which weighs down the action in Act 1. The music for Acts 2 and 3 is somewhat better and more varied but even with breakout scenes and solos there is no melody or music that sticks in the memory. Vocal lines meander over a straitened, largely rudimentary counterpoint. The color resources and scoring possibilities of the orchestra are barely touched.

The debut libretto by actress-filmmaker Kasi Lemmons is problematic as well, lurching from banalities to adolescent vulgarities and straining for poetic heights in its homespun repeated phrases, only fitfully with success.

Still, there may yet be a worthy opera here but in its present expanded state—3 hours and 10 minutes with one intermission—Fire Shut Up in My Bones feels undeniably bloated. The added scenes seem like ill-judged padding that do nothing to advance the storyline—an extended dance sequence by male college cheerleaders (oddly with no music whatsoever) and a scene of Charles and friends being paddled while pledging a fraternity—straight out of Animal House without the wit.

Lyric Opera should have waited until Blanchard’s opera was hammered into a more convincing piece before rushing to get in line to give it the big-stage treatment. As it now stands, Fire Shut Up in My Bones feels like a promising work with potential that still needs a whole lot of work.

That’s too bad because the large cast of African-American singers was uniformly excellent from top to bottom, as vocally assured as they were dramatically credible in their naturalistic acting.

Baritone Will Liverman was simply terrific in the principal role of Charles. The former Ryan Opera Center member’s voice has grown larger and more imposing since his Chicago days, and he sang with an emotional depth and honest integrity that gave this wayward opera its finest moments. Liverman’s acting was on the same level, putting across all of Charles’ loneliness, social and sexual doubts, angry determination to exact vengeance on his abuser as well as his ultimate mature acceptance.

Latonia Moore was just as inspired as Billie, Charles’ supportive mother. If aspects of Billie’s volatile side—as a literal pistol-packing mama ready to shoot her man’s lover—verged on cartoonish, Moore brought a big soprano voice and warmly sympathetic presence to the role. Their scenes together elevated the entire show. If only Blanchard had given these fine singers music more worthy of their talents.

Brittany Renee—replacing Jacqueline Echols—did what she could with the allegorical roles of Destiny and Loneliness, one of the least inspired elements of Lemmons’ libretto. In addition to upstaging the crucial scenes, she was an omnipresent witness rolling across the walls with undulating arm movements and succeeding only in detracting from the main action. Renee’s singing and acting skills were shown to better advantage in the flesh-and-blood role of Greta, the engaging woman with whom Charles has a brief but intense romance.

As the young Charles, Benjamin Preacely sang with the commitment and fervor of a seasoned adult trouper. Chauncey Packer embodied the role of Spinner, Charles’ womanizing, no-account father with his swaggering presence and Sportin’ Life-like high tenor (a role he has also sung to acclaim).

Chris Kenney, another Ryan Center alum, was aptly odious as Charles’ older cousin Chester who molests him at age 7. Kenney conveyed the duplicitous nature of this superficially charming but dangerous and violent predator.

Reginald Smith Jr. brought a big, likable presence and booming baritone to Charles’ Uncle Paul, a farmer who offers the most positive role model for the young boy. The large supporting cast filled out their assignments with esteem, especially Leroy Davis as the Pastor in a rousing church service.

In her main-stage Lyric debut, Daniela Candillari conducted the Lyric Opera Orchestra capably though had little success disguising the pallidness of Blanchard’s musical invention, especially in Act I, which at times seemed interminable.

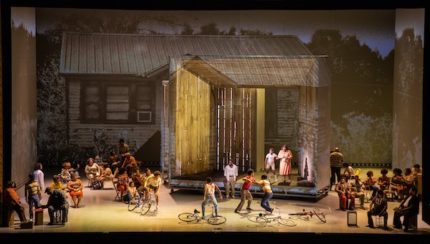

Allen Moyer’s economical scenic design got the job done efficiently with a revolving center-stage set for a variety of settings. Co-directors James Robinson and Camille A. Brown gave the lively moments vital energy while moving the action fluently.

Fire Shut Up in My Bones runs through April 8. lyricopera.org

Posted in Performances

Posted Apr 07, 2022 at 12:37 pm by Peter DG

We went to the Wednesday April 6 matinee and were surprised by the lead cast changes, presumably due to covid as of April 2 – Justin Austin for Liverman, Whitney Morrison for L.Moore, Brittany Renee for J.Echols, and a few others. Still the singers were fabulous to my “non critics” ear. Acting was OK, though the original cast was probably better. Surprised this was not noted previously.

Posted Apr 09, 2022 at 7:46 am by Stephen Bubul

For a dissenting view (and evidence that there’s no accounting for taste): I saw the Met HD Live production of this opera, and was so impressed that I went home and began researching the opera. Discovered that is was on Lyric Opera’s calendar in spring, 2022, so instantly bought tickets (I live in Minneapolis).I’m a musician and composer who prefers contemporary opera to the war horses any day.

And while many recent operas have a bland, generic “modern music” quality, I felt that Blanchard’s score was exceptional. He deftly weaves jazz and more traditional “classical” idioms with grace and skill. The music supports, and sometimes drives, the drama, in a way that Puccini would admire. And about that old chestnut of a complaint, “there are no great melodies”; well, I heard them as clear as bells, and they resonated even stronger in this second listening.

So I see not a flawed, unfinished work, but one the best new operas in the last two decades. Happily for music and opera lovers, I believe my take is dominant one, judging from reviews and the genuine responses of audiences, at the Met and in Chicago. (The excitement in the house was palplabe.)